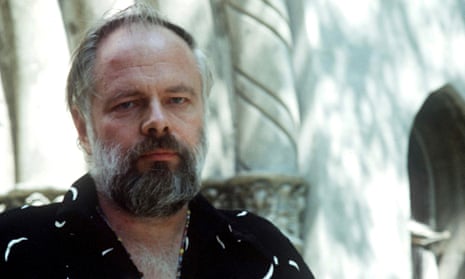

A Scanner Darkly is one of Philip K Dick’s most famous but also most divisive novels. Written in 1973 but not published until 1977, it marks the boundary between PKD’s mid-career novels that were clearly works of science fiction, including The Man in the High Castle and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and his late-career work that had arguably left that genre behind. Like VALIS and The Divine Invasion that followed it, A Scanner Darkly was two stories collided into one – a roughly science-fictional premise built around a mind-destroying drug, and a grittily realistic autobiographical depiction of PKD’s time living among drug addicts.

It is also, in the thinking of writer, critic and mathematician Rudy Rucker, the first work of a literary movement he would name “transrealism” in his 1983 essay A Transrealist Manifesto. Three decades later, Rucker’s essay has as much relevance to contemporary literature as ever. But while Rucker was writing at a time when science fiction and mainstream literature appeared starkly divided, today the two are increasingly hard to separate. It seems that here in the early 21st century, the literary movement Rucker called for is finally reaching its fruition.

Transrealism argues for an approach to writing novels routed first and foremost in reality. It rejects artificial constructs like plot and archetypal characters, in favour of real events and people, drawn directly from the author’s experience. But through this realist tapestry, the author threads a singular, impossibly fantastic idea, often one drawn from the playbook of science fiction, fantasy and horror. So the transrealist author who creates a detailed and realistic depiction of American high-school life will then shatter it open with the discovery of an alien flying saucer that confers super-powers on an otherwise ordinary young man.

It’s informative to list a few works that do not qualify as transrealism to understand Rucker’s intent more fully. Popular fantasy or science fiction stories like Harry Potter or The Hunger Games lack a strong enough reality to be discussed as transrealism. Apparently realistic narratives that sometimes contain fantastic elements, like the high-tech gizmos of spy thrillers, also fail as transrealism because their plots and archetypal characters are very far from real. Transrealism aims for a very specific combination of the real and the fantastic, for a very specific purpose, that seems to have become tremendously relevant for contemporary readers.

The potential list of transrealist authors is both contentious and fascinating. Margaret Atwood for The Handmaid’s Tale and her novels from Oryx and Crake onwards. Stephen King, when at his best describing the lives of blue-collar America shattered by supernatural horrors. Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo and David Foster Wallace, among other big names of American letters. Iain Banks in novels like Whit and The Bridge. JG Ballard, as one of many writers originating from the science-fiction genre to pioneer transrealist techniques. Martin Amis in Time’s Arrow, among others.

This proliferation of the fantastic in contemporary fiction has at times been described as the “mainstreaming of science fiction”. But sci-fi continues on much as it ever has, producing various escapist fantasies for readers who want time out from reality. And of course there’s no shortage of purely realist novels populating Booker prize lists and elsewhere. Both sci-fi and realism provide a measure of comfort – one by showing us the escape hatch from mundane reality, the other by reassuring us the reality we really upon is fixed, stable and unchanging. Transrealism is meant to be uncomfortable, by telling us that our reality is at best constructed, at worst non-existent, and allowing us no escape from that realisation.

“Transrealism is a revolutionary art form. A major tool in mass thought-control is the myth of consensus reality. Hand in hand with this myth goes the notion of a ‘normal person’.” Rucker’s formulation of transrealism as revolutionary becomes especially meaningful when compared to the uses transrealism is put to by the best of its practitioners. Atwood, Pynchon and Foster-Wallace all employed transrealist techniques to challenge the ways that “consensus reality” defined who was normal and who was not, from the political oppression of women to the spiritual death inflicted on us all by modern consumerism.

Today transrealism underpins much of the most radical and challenging work in contemporary literature. Colson Whitehead’s intelligent dissection of the underpinnings of racism in The Intuitionist and his New York Times transrealist twist on the zombie-apocalypse novel, Zone One. Monica Byrne’s hallucinatory road-trip across the future of the developing world and the lives of women caught between poverty and high-speed technological change in The Girl in the Road. Matt Haig’s compulsive young adult novel The Humans, which invites the reader to see human life through alien eyes. Transrealism has 30 years of history behind it, but it’s in the next 30 years that it may well define literature as we come to know it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion