Story highlights

NEW: A nurse who was quarantined at a hospital in New Jersey is released

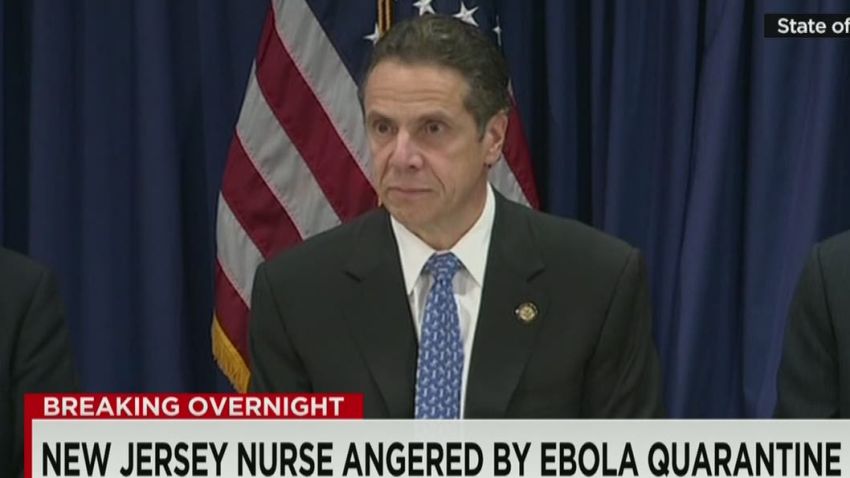

The New York and New Jersey governors announce tighter rules

Health workers returning from West Africa will be home quarantined for 3 weeks

A weekend of back-and-forth between two governors, the federal government and a nurse about mandatory quarantines left more questions than answers.

At the heart of the debate: Would such quarantines on health workers who just came back from treating Ebola patients in West Africa help prevent the spread of the virus, or would they discourage medical aid workers from helping fight the global crisis?

Here’s what we know about the latest Ebola policies:

Who enacted tougher rules for health workers?

New York, New Jersey and Illinois say anyone returning from having direct contact with Ebola patients in West Africa will have to be quarantined for 21 days. The 21-day period marks the maximum incubation period for Ebola.

Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn’s office said the quarantine would be a “home quarantine.”

“This protective measure is too important to be voluntary,” Quinn said.

When New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced their new policies on Friday, they called for hospitalization or quarantine. But on Sunday night, after debate over the policies heated up, the governors said the quarantines could be carried out at home.

Cuomo, Christie clarify policy on Ebola health worker quarantines

Would home quarantines even work?

Depends on which side you ask.

Neither Christie nor Cuomo explained how a home quarantine would work if family members were also in the home. It’s also unclear how a home quarantine would or could be enforced if the quarantined person chose to leave the house.

On the other hand, the governors say something had to be done; that asking returning medical workers to voluntarily quarantine themselves hasn’t worked.

Public health experts say there’s plenty of scientific evidence indicating there’s very little chance that a random people will get Ebola, unless they are in very close contact – close enough to touch bodily fluids – with someone who has it.

Still, there’s also a sense that authorities have to do something because of Americans’ fears – rational or not – and the belief that the country is better off safe than sorry.

As Mike Osterholm, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota, says, “You want to try to eliminate not just real risk, but perceived risk.”

What led up to the policies?

Not long after she returned home from covering Ebola in Liberia, NBC medical correspondent Dr. Nancy Snyderman violated her voluntary quarantine in New Jersey to pick up takeout from a restaurant in October – even after her colleague became infected.

In New York, city workers scrambled to retrace the steps of Dr. Craig Spencer, who tested positive last week. He’d been on the subway and to a bowling alley, among other places.

What are the concerns about such quarantines?

The concerns are twofold: One, it could deter doctors and nurses from traveling to West Africa to help rid Ebola; and two, it could greatly impede the livelihoods of health care workers.

“If I lose three weeks on my return and don’t get to do the work I’m supposed to do … means this wouldn’t be workable for me,” said Dr. John Carlson, a pediatric immunologist at Tulane University.

The director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expressed a similar view earlier this month, arguing that stringent travel restrictions might create more problems than they solve.

“It makes it hard to get health workers in, because they can’t get out,” Dr. Tom Frieden said.

“If we make it harder to respond to the outbreak in West Africa, it will spread not only in those three countries (in West Africa hit hardest by Ebola), but to other parts of Africa and ultimately increase the risk here” in the United States.

Who would pay for the time off?

Cuomo added that if employers don’t pay quarantined workers for the time they are absent while under quarantine, “the government will.”

How has this affected health care workers?

The same day the governors announced their tougher policies Friday, nurse Kaci Hickox arrived at Newark Liberty Airport after spending a month helping treat Ebola patients in Sierra Leone.

She didn’t have any symptoms and tested negative for Ebola. Nonetheless, the nurse from Kent, Maine, was holed up inside a quarantine tent at University Hospital in Newark over the weekend.

She was released from the hospital Monday, according to her attorney, and will return to Maine.

“This is an extreme that is really unacceptable, and I feel like my basic human rights have been violated,” Hickox told CNN’s Candy Crowley on “State of the Union” on Sunday.

She slammed Christie for describing her as “obviously ill.”

“First of all, I don’t think he’s a doctor. Secondly, he’s never laid eyes on me. And thirdly, I’ve been asymptomatic since I’ve been here,” Hickox said.

Is Hickox’s quarantine unconstitutional?

Attorney Stephen Hyman said there’s a “legal basis” to challenge the quarantine policies in New Jersey and in New York, but the nurse isn’t sure she wants to do so.

Christie said he was glad that Hickox had been released and defended his actions.

“The reason she was put in the hospital in the first place was because she was running a high fever and was symptomatic. If you live in New Jersey, you’re quarantined in your home.

“That’s always been the policy. If you live outside the state, and you’re symptomatic, we’re not letting you go onto public transportation. It makes no common sense. The minute she was no longer symptomatic, she was released,” the governor said.

Hickox said she has nothing to recover from. Her temperature is normal, and she feels fine.

Who else might amp up Ebola rules?

Florida is starting mandatory monitoring for all travelers returning from West Africa, and Virginia is following suit.

“Virginia will implement an active monitoring program on Monday for all returning passengers from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, with a special emphasis on returning health care workers,” said Virginia governor spokesman Brian Coy.

Cuomo says he knows some people probably think he’s overreacting.

“We’re staying one step ahead,” the governor said. “Some people will say we are being too cautious. I’ll take that criticism because that’s better than the alternative.”

Isn’t there a middle ground?

There is.

One possibility is to have those travelers go through more than just temperature checks.

Dr. Irwin Redlener, director of Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness, says one such measure could be checking daily for decreases in white blood cell counts or platelets – which could be, but aren’t necessarily, a sign of an Ebola infection.

And Osterholm thinks there should be stricter controls on what a person who arrives from West Africa does in his or her first three weeks in the United States. For instance, he thinks such a person shouldn’t take public transportation or go to crowded places like bowling alleys – both of which officials say Spencer did before he was symptomatic.

CNN’s Elizabeth Cohen, Ray Sanchez, Sara Fischer, Joe Sutton and Ralph Ellis contributed to this report.