One of the most useful tools we had while our kids were in middle and high school was the online access to their grades. On a daily basis, we could check to make sure they were turning in their assignments or if their study methods had paid off on the latest quiz. The report card's arrival in the mail became a non-event, since we already knew what it would say and the specific achievements and struggles that led to the grades they got.

As my daughter and then my son went off to college, I knew we would face a cold turkey situation, from total access to school records to no right to information from the school at all. Zilch. Many parents in this situation tell their children that if they want financial help for college, they are expected to fess up about their grades.

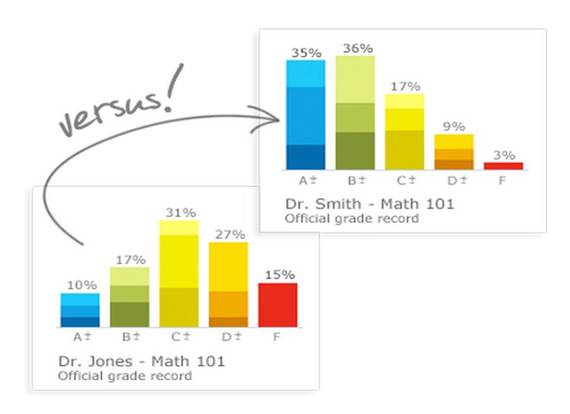

We've taken a different approach. Instead of asking about grades, we ask our adult children to occasionally share with us something they do for a class, an artifact of their college experience. We repress our curiosity about grades because we do not want to contribute to a pernicious trend in higher education in which students engage in strategies to find "easy" classes. Guiding students to the "easy A" has become an industry on many campuses, often with the overt blessing of universities that hand over data on grade distributions leading to websites and phone apps that lure in students with ads like the one shown below.

For students worried about their grades, it is rational to follow this data. But it undermines learning, since by definition an "easy grader" is expecting less of students. The class may be entertaining, and students surely learn something, but when students are not really challenged they do not make the kind of cognitive gains that college should be about. Taking a less demanding class every now and then is okay. But making a college career out of it means not getting their (our) money's worth out of college.

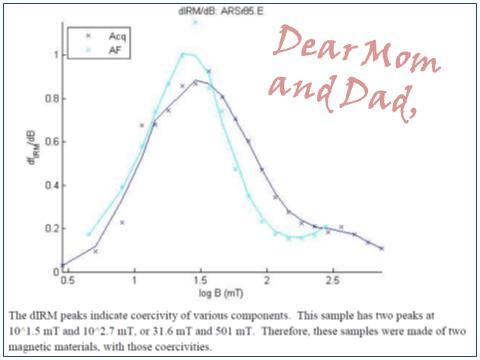

Instead of asking about grades, we ask our children to share with us, at least once each term, a test, a paper, or any other school project of their choosing. Our son just started college in September and recently sent us a copy of a paper he wrote for a literature class, in which he described a story he read as "showing that when love gets in the way of all other aspects of life, it can be cathartic and liberating to let it go." (We gave it an A). At the end of her first year, our daughter sent us a paper about "true polar wobble," using the magnetism in rocks to investigate the idea that the magnetic North Pole rotated down to where the equator is and then back up in a geologically short period of time. One of her artifacts in her second year was a video of her making a scientific presentation. It was about alcohol distillation, a more illuminating update than any report card ever would have been.

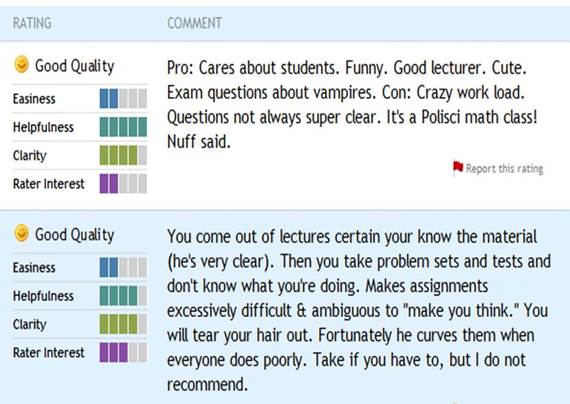

It is not just the grade distributions data that undermine rigor. Professor ratings typically include opinions about how easy a class was. The political science professor in the example below is apparently witty, helpful, clear and even cute. Yet he gets dinged because he asks ambiguous questions that make you "tear your hair out" because he is trying -- student mocking the professor's words -- to "make you think."

Of course, making students think -- rather than simply asking them to memorize, regurgitate and calculate -- is exactly what a good instructor does. However, being an excellent teacher does not necessarily yield high ratings from students. In a recent study, instructors whose students actually advanced the most academically were rated poorly by those students. It turns out that students, especially those who are less well=prepared, do not appreciate the effectiveness of an instructor who is more demanding, even when it works in terms of learning. The problem is so bad that a department head told me that the way to save a program that is having difficulty attracting enrollment is to start giving a lot of A's. Suddenly, students start flocking to the door.

Obviously, parental pressure is not the only reason that students seek out easier classes. But we hope that by asking our children for samples of what they are doing rather than report cards, we can help tilt them toward the hard, fun academic work that college should be about.