Moustafa Bayoumi: the opera’s grasp of history is fundamentally flawed

The problem with the Metropolitan Opera’s new production of The Death of Klinghoffer isn’t that it’s antisemitic. Some grotesque antisemitic statements are made during the performance, especially by Rambo, the most degenerate of the hijackers of the Achille Lauro. But his antisemitism is offered as proof of his depravity, and if you can’t tell the difference between a character’s lines and the larger message of a work of art, you’re probably better off watching reality TV.

But there is a problem, though it’s also not that the opera is skewed to the hijackers, as some protesters have suggested. The emotional heart of the opera is Leon Klinghoffer’s wife Marilyn, whose shattering final aria — beautifully sung by Michaela Martens — ends with the words “They should have killed me/I wanted to die.” How can the audience not empathise with her terrible loss?

Nor is the problem that this production seeks to rationalise or humanise terrorism. Art should never shy away from the muck of the world, and to understand something is not the same as to condone it. But while the Palestinians may be afforded some rather limited depth – the hijacker Mamoud especially – the Palestinians are mostly lurking figures of vengeance, and this production is still firmly ensconced in a theatrical tableau of dark-skinned men with guns terrorising innocent whites.

This is not to say that Klinghoffer should not be staged. As an opera, it’s thrilling and dynamic. But it’s flawed.

The racial dynamic is not the problem, though. History is. Klinghoffer’s claim to artistic relevance is that it’s based on a real event, and the opera proudly announces itself as historically intelligent by beginning with narratives of Palestinian and Israeli history in two different but parallel choruses: the chorus of exiled Palestinians and the chorus of exiled Jews, gesturing to a fearful symmetry between Israeli and Palestinian experiences. But false symmetry creates false history here.

Palestinian history in Klinghoffer is staged as Muslim only – and only as fundamentalist Muslim, which is wrong and dangerous. The group that carried out the Achille Lauro operation, the Palestinian Liberation Front, was a Marxist-Leninist faction, an offshoot (twice removed) of the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which was led by the Christian Palestinian George Habash. But if you watched Klinghoffer, you’d have no idea Marxist Palestinians even existed, or that Christian Palestinians were at the forefront of much of the Palestinian national movement.

In fact, by the end of the first chorus, each of the Palestinians is raising a finger (a symbol used by Isis, no less) while parading plain green proto-Hamas flags around the stage. Why green flags over the Palestinian flag? Why does the Palestinian chorus end with “Our faith will take the stones he broke/And break his teeth,” as if Palestinians are only of one faith? And why does the Palestinian woman in Muslim clothing push Omar to killing for Islam? Are all Palestinians Muslim, and all Muslims violent?

Klinghoffer wants to collapse the complexities of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians into a timeless religious battle between Muslims and Jews.

Like the next guy, I find it annoying when historians pedantically tell you which little facts are wrong in a work of art based on history, but my point is not about the details. By suggesting that this conflict is based in religion and not in territory, Klinghoffer removes much of the history (and people) of this conflict and replaces it with a mythic clash of civilisations. Ironically, this is the same clash of civilisations that was driving the protesters outside the opera house last night.

Kayla Epstein: I would strongly urge members of my community to see it

As this panel’s Orthodox Jewish participant, I’m aware that I’ve been asked to participate for a very specific purpose: to bring the bearing of my religious and cultural upbringing to the question of whether The Death of Klinghoffer is antisemitic.

So let’s just get that out of the way: the answer is no.

I can understand why some would jump to to that conclusion, especially if they haven’t seen the opera. Klinghoffer forces Jewish audiences to confront some uncomfortable aspects of Israel’s history, and to relive a tragic chapter in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There are some antisemitic lines delivered by one of the hijackers: “America is one big Jew,” he sneers at his cowering captives. But his brutal actions and the shrill, frenzied music that accompanies his words so clearly prove him a villain that it’s ridiculous to say composer John Adams and his librettist Alice Goodman are promoting that view.

Though two opposing sides are given the opportunity, over three hours, to present their narratives, it’s crucial to remember who gets the last word. Klinghoffer ends with a beautiful, heartbreaking aria by his widow Marilyn, who has just learned of the death of her husband. “I wanted to die,” she cries out. The finale lays bare the suffering and anguish that terrorism and antisemitism has wrought.

So why the outrage? Because there’s a lot of ignorance out there drowning out the facts about what this opera is about.

That’s really what’s so insidious about the protests to stop Klinghoffer being performed – it prevents people from drawing their own conclusions about it. Many of the people picketing Lincoln Center on Monday night have not seen it – and the chances are that most of them haven’t even had the opportunity to see it, since similar protests (or the fear of inciting them) have kept companies from staging the opera. This ignorance is self-perpetuating.

If this opera has a purpose, it’s to force its viewers to hear and experience perspectives that they wouldn’t ordinarily listen to, and in fact may be determinedly avoiding. “If think if you should talk like this/Sitting among your enemies/Peace would come,” sings the captain, the show’s moral compass.

I would strongly urge everyone to go see Klinghoffer. Don’t let anyone’s opinions stand in for your own. Definitely don’t let the opinion of a politician with a very troubled track record on freedom of expression and the arts stand in for your own.

See it, even if you believe it will be uncomfortable – especially if you believe it will be uncomfortable.

After all, the worst thing that could happen is that it will force you to think for yourself.

Alan Yuhas: all the deft touch of a sledgehammer

Three little old ladies in opera finery put on their own show during The Death of Klinghoffer, just a few dozen feet from the stage. After sniggering and snarling like bored teens at a school assembly, they cawed “bastards!” and “Nazis!” at the end of the act. During the intermission, a woman in the row ahead of them asked them to respect the performers and audience, saying “It’s great art!” They responded as a chorus.

“There’s a 400-year tradition of booing at the opera!”

“This is Nazi propaganda!”

“Political lies on the iconic stage of the Met! Where’s the Jewish side of the narrative?”

The woman in front of them, flummoxed, said she was of Jewish descent and had relatives who were Holocaust survivors. She started to say the Klinghoffers’ Jewish perspective gets the spotlight in the next act, but the chorus, almost in unison, had cut her off already: “Shame on you!”

Watching the miniature altercation play out a few rows away, I couldn’t help but wonder whether the opera was really that controversial, and whether it was either all that political or all that great.

Setting aside the curious charge that the Palestinian terrorists, who were human beings and are compared to beasts by a major character, are unnecessarily humanised, protesters say the opera romanticises terrorism. But the first act did not romanticise Palestinian terrorists so much as show how a young person’s romantic idea of war, nationalism and sacrifice could be corrupted horribly – an idea at least as old as Lord Byron two centuries ago. The violence is depicted as abhorrent throughout – dissonant harmonies and weird percussive shifts, brutal and bestial in the terrorists, and condemned by Klinghoffer and others.

More political and muddled were sequences about Israel and the Palestinian territories, full of nature imagery and religious allusions but not particularly pointed or poignant. Some of it worked: a Jewish love song between husband, wife and country, the many meanings of walls, and the funereal song of the Palestinians. Some of it did not, at least for my non-operatic sensibilities: the religious language felt heavy-handed, the narrative frame of survivors looking back didn’t offer clarity or depth, and the symbols of faith and nations (like trees and green flags) were earnest but reductive.

As for the art, it was not enough to keep the hecklers from leaving at the half. With the deft touch of a sledgehammer, the opera reminds us over and over that we are all human beings, regardless of race and religion. It does a vastly better job – carried by the performers – of dwelling on loss, and lines like “Nobody really cares except the sufferers,” have resonance that transcends the play’s knottiness. The score has some brilliant passages, and the orchestra, as usual, was up to the task. The first aria sung by Klinghoffer (Alan Opie) and the final one sung by his wife Marilyn (Michaela Martens) are also exceptional, especially as she turns on the cruise’s “neutral” captain and turns the opera into a dirge, which is what it should have been all along.

Eli Valley: transcendent art woven from two narratives

I emerged from the Met overcome by an overarching clarity: how could we have been so foolish all these years? The terrorists were right about Israel, they were right about America: the Jews are the enemy and the Jewish state must be destroyed.

Of course, that didn’t happen, despite the fury of those with the weakest faith in human intellect — and maybe the greatest faith in the hypnotic power of art. The Death of Klinghoffer is an anguished meditation on two paralysed and drowning peoples, and the fury is that borne by seemingly every Jewish leader in the tri-state area. It’s important to ignore art critics who don’t look at art, so I entered the theater expecting nothing but that the show would be interrupted early and often.

Sure enough, a guy in a fancy section started shouting “The murder of Klinghoffer will never be forgiven!” He chanted this over and over, and in such a rhythmic intonation that I thought it was part of the opera, but apparently he was trying to snap us out of the Taliban training tutorial he’d come to sabotage.

We were all on this ship; the stage set packed us into the stern. And with the help of exquisite production design, which morphed ocean waves into desert landscapes and back again, we were all in Palestine and in Israel. A chorus of exiled Palestinians opened things up, speaking of a father’s house in 1948: “not a wall in which a bird might nest was left to stand”. Echoing the story of Noah, and depicting the Nakba as an all-consuming flood is not an act of antisemitism, but it’s certainly a detour from your typical Yom Ha’atzmaut gala. But then the chorus of exiled Jews came to provide the Zionist narrative: “Then we shall rise, miraculously, virgin, boy and bride.”

In the eyes of the protesters, that’s probably the opera’s cardinal sin: it presents two narratives drifting together at sea. Just as both choruses roam the ship, the narratives are intertwined and overlap — and end up against the backdrop of the wall: one narrative’s security wall, the other’s apartheid wall, built decades after the highjacking the opera depicts but serving as the inevitable destiny of both Palestinian and Jewish history.

Is that all the critics fear? Protesting the production, Zionist Organization of America’s Morton Klein argues “Art should be truthful.” That’s false on its surface, and Klein uses the the same press release to push a single side’s truth (on 1948: “Jewish leaders begged the Arabs to remain in their homes and to live together in peace.”). But even in the parts of the opera that are true to the antisemitic hatred of a particular character, the protesters don’t seem to be concerned with authenticity but rather with nuance and narrative.

They insist we’re being indoctrinated — or as one law professor said: “It’s similar to the language used by Joseph Goebbels.” Possibly, yes, but where does it follow that the makers of the opera are trying to indoctrinate people to become that character? The fear is not that we will become characters out of the opera, but that their narratives might become real.

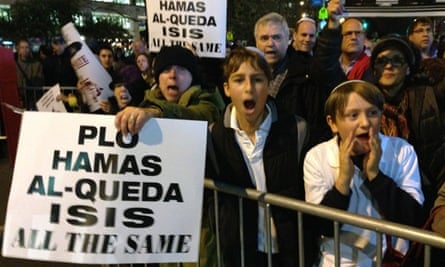

Before the opera began, I went outside to the protests, and I saw groups like this:

Watching the kids with signs, I wondered which of these productions – inside the Met or on the street outside – was the real operatic stew of indoctrination and incitement, an intricately choreographed production of paralysis in Palestine. As if to reinforce the point, a cheerful woman was passing out a mock-up of the Met’s playbill, photoshopped with an image from an Isis beheading video.

Reinforcing the tenor of the placards, Brooklyn assemblyman Dov Hikind has said, “What are we going to do next, down the line? Have an opera about Isis? About al-Qaida?” Yes, of course we should. Since when does representation equal reverence? Every Passover we depict slavery to remember the past. Would Hikind ban the seder? On Purim we act out Haman’s genocidal plot. Would Hikind outlaw the Purim Spiel? But where else would he get to play dress-up? Ah, but one might counter: the problem is not the depiction but the fact that we might be justifying, even lionising the other.

There was none of that in this opera. All there was was two narratives caught up on a ship.

Behind the police barricades, cordoned off into narrow byways, the protesters look like they’re on their own ship moored on the Upper West Side.

And just as inside the theatre the audience becomes part of the ship, these people seem to be stuck on their own Achille Lauro, where every Palestinian is a terrorist and every terrorist has no backstory, nothing that might make their narrative nuanced, their history heartbreaking. Which isn’t to say justified or glorified, simply three-dimensional. Speakers at these rallies, op-ed warriors, parents who ship their kids to march with signs reading “tenors and terrorists don’t mix” — they’re frozen on this ship in 1985, where every Arab is cleanly and neatly recognisable as a murderer.

And here’s the power of art, just one of countless ways a creative work can bend the mind in a manner that can make us happy we have human capacities. Back in the theatre, at one point we see the tide off the ship’s deck projected against the large backdrop screen. But it’s an overhead view, so it looks like a waterfall. And then we see this same waterfall flowing over the separation/apartheid wall at the left.

Almost imperceptibly, everything seems to shift: the wall on the left looks like the outside of a giant ship. You can read this a lot of ways, but together with the repeated bird imagery – the ship’s captain even tells of one landing on his arm – suddenly the entire ship seemed to be like a Noah’s Ark built out of the separation wall. The world is destroyed, and Israelis and Palestinians are packed together in their frozen/floating capsule built out of the giant wall encasing them. The whole time, everyone is paralysed and at risk of being thrown overboard. As the body of Klinghoffer himself says, “Nothing is lost, but the sea level has risen fast against the sea wall.” That moment, when I was staring at the waterfall and the wall seemed to shift itself into an ark – the production achieved a transformative level of transcendence. It’s subjective of course; I don’t pretend this is the official true reading of the opera. But that’s the point, and it’s one of the reasons art is the last thing in the world we should want to suppress and censor.

At another point in the show, as we approach the moment Leon Klinghoffer is murdered, a man got up in the balcony. I had a flash: is he a protester? Is he gonna take out a gun? Has he interwoven the art with ideology so insanely that he’s been driven to kill the actor playing the killer? Given the hysteria that’s surrounded the production, I really thought that was a risk, and I wondered whether I could race to the balcony on time to stop him. But thankfully it was just a guy stretching his legs and craning to get a better view.

And then Leon Klinghoffer is murdered, and the people in the audience, on the ship, silently gasp, because the tragedy on stage is as real as it is horrifying, heartbreaking history, and it is art.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion