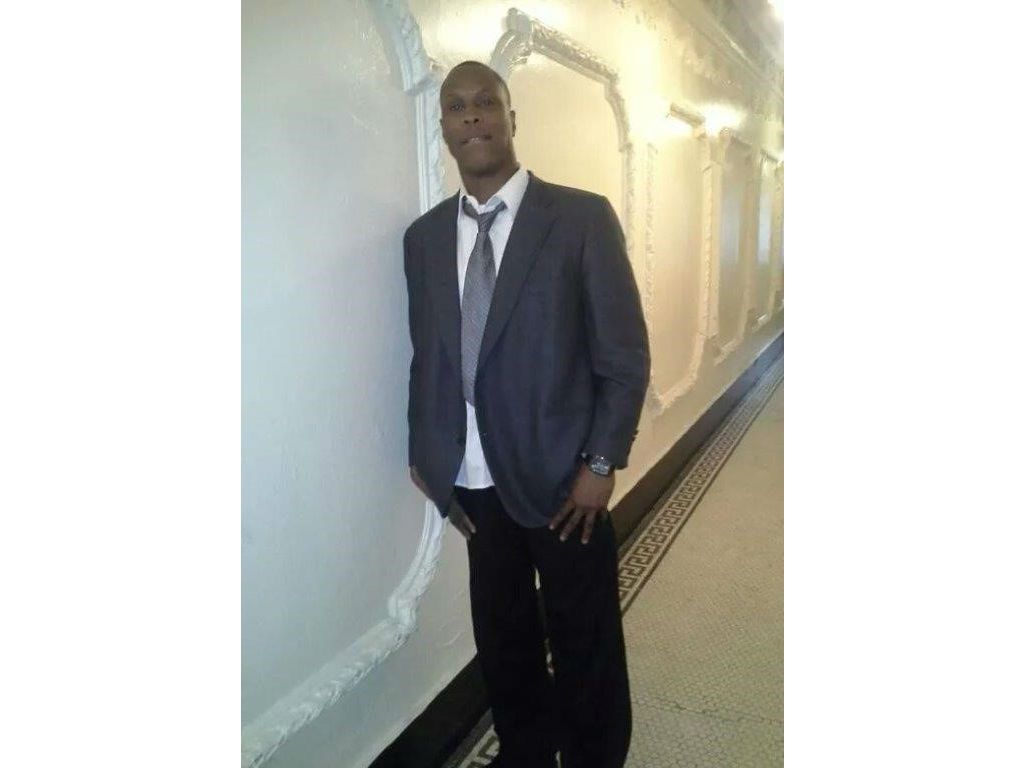

In Spring 2008, things were finally looking up for Davino Watson. He had pleaded guilty to selling a small amount of cocaine in September 2007 in New York, but on May 8, the 23-year-old successfully completed the state's Shock Incarceration Program, a bootcamp-style lockup for non-violent and non-sexual offenders. But "three seconds" after Watson's release, he tells Newsweek, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents cuffed him and began deportation proceedings, alleging he was in the country illegally. Watson then spent the next three-and-a-half years mostly in ICE's Buffalo, New York jail, fighting to stay in the United States.

But Watson was a U.S. citizen during his entire 1,273-day detention. In fact, he has been a citizen since 2002, as he repeatedly told the agents during his detention. Under U.S. law, ICE cannot detain U.S. citizens. ICE documents indicate that the agency realized its error in November 2011. A federal lawsuit filed October 31 in the Eastern District of New York details Watson's kafkaesque ordeal, but immigration law experts estimate that thousands more Americans have and continue to contend with similar detentions. Some, including individuals with mental disabilities, have even been deported.

Davino Watson was born in Jamaica on Nov. 17, 1984. He arrived in the U.S. on Aug. 4, 1998 as a lawful permanent resident to join his father and step mother, who already lived in the U.S. He became a citizen under the Child Citizenship Act of 2000, a law that allows children under 18, who are lawful permanent residents, to automatically become citizens when their parents naturalize. Children who become citizens under this law do not have to submit any additional paperwork. In addition, American immigration law considered Watson to be "legitimated;" simply put that means Watson is legally considered his biological father's son even though his parents were unmarried at the time of his birth. American immigration law recognizes a Jamaican law abolishing "any legal distinctions based on legitimation in 1976," Watson's lawyers, Mark A. Flessner, Christopher G. Kelly, and Robert J. Burns of Chicago's Holland & Knight LLP, and Mark Fleming of the National Immigrant Justice Center, say in the suit. So when Davino Watson's dad, Hopeton Watson, became a U.S. citizen on Sept. 17, 2002, Davino also became a citizen that same day.

About a month after Watson entered Shock incarceration, an ICE officer interviewed him. Watson says he told the officer that he is a citizen and gave the agent his parents' phone number. The officer took down the number and didn't issue an immigration detainer (a notice to law enforcement that ICE will detain an inmate upon his or her release), but "never" followed up with Watson's parents to confirm his citizenship claim, the suit charges. In April, another ICE agent investigated Watson's citizenship status -- and whether he could be deported. Somehow the officer reported that "his parents are nationals and citizens of Jamaica who have not naturalized. No issue of derivation applies."

Watson's attorneys maintain this agent failed to thoroughly investigate his claim, saying that "with minimal, reasonable investigation" the officer would have found that Watson is a citizen. When ICE detained Watson that May, he repeatedly told agents that he was a citizen and even procured a copy of his dad's certificate of naturalization. And yet ICE agents "did nothing" to corroborate these claims and pushed forward with deportation proceedings, Watson says.

Because detention is considered a civil matter, Watson did not have a right to court-appointed counsel granted to indigent, criminal defendants. He had to defend himself against deportation until his case reached the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which appointed him a lawyer.The Second Circuit reversed immigration court's' earlier decisions in May 2011 and required the Board of Immigration Appeals hear Watson's case.

Finally, in November 2011, the ICE Buffalo Field Officer Director wrote in a memorandum included in the lawsuit that "Watson has provided probative evidence of United States citzenship...It is recommended that he be immediately released from DHS custody."

When Watson got out, however, his problems with ICE were far from over. According to Watson, ICE didn't stop deportation proceedings or give him "proof of legal status or work authorization" for 755 days. Without this proof, he couldn't work, "leaving him unemployed, destitute, and otherwise not able to exercise his rights and privileges as a U.S. citizen."

Watson tells Newsweek in an email that he wanted to go to school and "become a good member of society" when he graduated from the Shock program, and had "never felt so strong in life."

"Then ICE arrested me and took it all away. It was devastating," the Brooklyn resident says. He also missed his grandmother's funeral and nephew's birth during his detention.

A spokesman for ICE tells Newsweek that the agency doesn't comment on pending litigation.

ICE has issued several memorandums for dealing with detainees' claims of U.S. citizenship. The most recent memo on the subject, which is from November 2009, states:

If an individual already in custody claims to be a USC, an officer must immediately examine the merits ofthe claim and notify and consult with his or her local OCC. Ifthe individual is unrepresented, an officer must immediately provide the individual with the local Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) list ofpro bono legal service providers, even if one was previously provided.

DRO and OPLA must also jointly prepare and submit a memorandum examining the claim and recommending a course of action to the HQDRO Assistant Director for Operations at the "USC Claims DRO" e-mailbox and to the HQOPLA Director ofField Operations at the "OPLA Field Legal OPS" e-mailbox. Absent extraordinary circumstances, this memorandum should be submitted no more than 24 hours from the time the individual made the claim. HQDRO and HQOPLA will respond to the field with a decision on the recommendation within 24 hours. A notation should be made in EARM and a copy ofthe memorandum and resulting decision should be placed in the alien's A-file. The memorandum and resulting decision should also be saved in GEMS and notated using the designated GEMS barcode.

If the individual's claim is credible on its face, or ifthe investigation results in probative evidence that the detained individual is a USC, the individual should be released from detention. Any significant change in circumstances should be reported to the "USC Claims DRO" e-mailbox and the "OPLA Field Legal Ops" e-mailbox.

Nonetheless ICE -- which placed some 500,000 detainers on people in fiscal years 2012 and 2013 according to researchers at Syracuse University -- still puts U.S. citizens in custody. Civil liberties advocates say this has been exacerbated by an ICE initiative called Secure Communities, which began in 2008. Billed by the agency as "a simple and common sense way to carry out ICE's priorities," it enables local law enforcement to share fingerprints with the Department of Homeland Security. (ICE is part of the DHS). Local law enforcement has long shared this data with the Federal Bureau of Investigation to see whether arrestees have a criminal record; per ICE, "under Secure Communities, the FBI automatically sends the fingerprints to DHS to check against its immigration databases."

Hard-and-fast data on the number of citizens unlawfully detained by ICE is not immediately available, and one expert tells Newsweek such a figure is so elusive it can be described as the "$64,000 question."

Several studies indicate that many U.S. citizens have been detained in recent years. In October 2011, University of California, Berkeley researchers analyzed Secure Communities data and found "1.6 percent of cases we analyzed were U.S. citizens and all were apprehended by ICE."

When they extrapolated said percentage to the number of ICE detainees since Secure Communities began, they found "that approximately 3,600 US citizens have been apprehended by ICE from the inception of the program through April 2011."

In more extreme cases, detention of citizens leads to deportation. In 2008 a mentally disabled U.S. citizen named Mark Lyttle was detained and deported to Mexico, where "he was "forced to live on the streets and in prison for months." Lyttle's lawyers announced in October 2012 they had settled a civil lawsuit against the federal government for $175,000.

Asked whether ICE is doing anything to prevent future detention of U.S. citizens, the spokesman said the agency is abiding by its policies.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Before joining Newsweek, Victoria Bekiempis worked at DNAinfo.com New York and the Village Voice. She also completed internships at news ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.