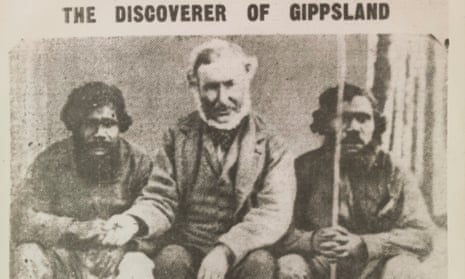

In 2011 I made an uncomfortable discovery about my family history. I had a famous great-great-great uncle, I learned: Angus McMillan. He was an explorer of early Australia, but in recent years he has also been identified as the man responsible for a series of massacres of the Gunai (sometimes referred to as the Gunaikurnai) people of Gippsland in the south-eastern state of Victoria.

These attacks were cold-blooded and without mercy. Men with guns descended upon unsuspecting encampments, killing men, women and children; they were killed, as one settler wrote later, “whenever [the Gunai] can be met with”. In the first 10 years of settlement in Gippsland, the Gunai population fell by more than 90%, to little more than 100 individuals.

McMillan had fled Scotland during the time of the Highland Clearances but, in a cruel irony, he went on to enact brutal clearances of his own upon his new country, the worst at Warrigal Creek in 1843, where 80 to 200 members of the Bratowooloong clan were killed in revenge for the murder of a single white settler.

My relative has come to embody some of the very worst excesses of Australian colonial history. And that is saying a lot for a country in which 20,000 of its Indigenous people are estimated to have died during the “frontier wars”, and where, until relatively recent history, tens of thousands of Aboriginal children were separated forcibly from their families and re-homed in orphanages or with white foster families.

On Thursday Australia will celebrate – although celebrate is perhaps the wrong word – an occasion known as National Sorry Day. This annual event is held as a gesture of apology to the Aboriginal population for the havoc wreaked upon their people by colonialism: in previous years, it has been marked by people marching through the streets, or by distributing black roses. Flags are lowered to half-mast, while above cloud-written apologies are writ large across the sky: “SORRY”. There is much to be sorry for.

Learning of my link to this disturbing chapter in our colonial history left me in a state of shock. I knew there had been some awful injustices in the British colonies, but to find such a vivid example in my own family tree was something else entirely. Since 2011 investigating this grisly episode has become a growing preoccupation, and one that finally drove me to travel to the other side of the world. I wanted to uncover the truth of McMillan’s actions and to meet face-to-face the Indigenous group who suffered at his hands.

I have now visited Gippsland three times, and there I met local historians, Gunai elders and those who work for the benefit of that community. The conversations we’ve had have required me to listen, and be humble. They have not always been easy, for the story of McMillan, and what came after him, is not a pleasant one.

Like many Indigenous peoples, the Gunai community today struggles with problems of addiction and violence – what some might call “diseases of despair”. In many ways, the overt violence of McMillan and his men did not have the worst impact, that came from the policies of “assimilation” that were later enacted upon the much weakened survivors: confinement to Christian missions, the banning of traditional customs, the breaking apart of families and other misguided attempts to “civilise” a culture that had pre-dated the settlers by tens of thousands of years.

For Australia’s Indigenous people, deep social problems arrived with the settlers and never departed. Life expectancy for this group is still 10 years lower than the Australian average, and the unemployment rate is three times higher. Indigenous children are 10 times more likely to be taken into care and 30 times more likely to suffer from malnutrition. Indigenous individuals are 15 times more likely to be imprisoned, eight times more likely to die from alcohol-related causes, and more than twice as likely to commit suicide.

They also suffer from endemic levels of racism: a 2012 survey of Indigenous people in Victoria found that 97% of respondents had been targets of verbal or physical abuse or discrimination over the previous year; 84% had been verbally abused; 67% had been spat at or had objects thrown at them; 66% told that they “did not belong” in their home towns; and 70% had suffered eight or more incidents over that single year.

With these statistics at the forefront of my mind, I was staggered by the gracious welcome I received from the Gunai community, many of whom were generous enough not only to meet me but to discuss in great depth the human consequences of McMillan and his peers’ actions, and the longer-term consequences. Ricky Mullett, for example, now the chief executive of the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Corporation (the body set up to manage what has been accepted by the court to be the Gunai people’s native territory), took me to a number of sites where massacres took place before putting me up at his own home.

I can only hope my efforts have made a small contribution to repairing old damage. I have written a book, Thicker Than Water, about my experience in the hope of furthering awareness and understanding of these dark, historical secrets.

For despite the advent of National Sorry Day, the “native title” legislation that returned ownership of land to the Gunai, and the admission of collective guilt and responsibility they imply, there is still a vocal segment of Australian society that makes great efforts to downplay the significance and impact of frontier violence and assimilation policies, and denies the obligation of today’s generation to accept blame for the behaviour of their predecessors.

A great many of our political conversations today seem to revolve around such questions of collective colonial guilt. Should reparations be paid to the descendants of slaves? Should the British Museum return its ill-gotten gains? Must Rhodes fall?

In Gippsland, an analogous discussion is under way. Russell Broadbent, the Liberal MP for the McMillan electorate in Victoria, has asked the Australian Electoral Commission to rename his seat. “It would send a message of practical reconciliation,” he explained recently. “It would send a message that we actually care about these issues and, if we are not responsible to our past, we don’t understand our past, we can’t get on with our future.”

The request has met with a mixed response. Some have argued, not unreasonably, that erasing a name will not erase the past: it is a whitewash, perhaps, of a different kind. But although I understand their arguments, I disagree. It is a gesture, only. Of course it is. Yet many gestures – like National Sorry Day – are important and meaningful.

My journey to Gippsland, to meet the descendants of the victims of my relative, was a gesture too: I could not hope to undo the past. And yet to me – and, I hope, to those that I met – it was an extremely moving and meaningful experience, and one that left me with a better understanding of how such atrocities take place, and how we might hope to repair the damage they leave behind.

Thicker Than Water by Cal Flyn, is published on 2 June.