To speak with Françoise Mouly is to be inspired. As she describes it, "I've been lucky all my life to follow what I'm in love with." She is an art editor at the New Yorker, has been a transformative influence on comics in the U.S., and was knighted by the French government. So why start up TOON books, (comic) book publishing company? She follows what she is in love with, and in her case, that meant creating high quality comics for kids. Françoise knew intuitively how important comics were to the growth and development of her own children's literacy and love of reading, and she wanted to create that experience for a bigger audience.

I recently sat down to speak with Françoise for a Zoobean Expert on Air session about this work at TOON Books, parenting advice and much more. Here are three of my favorite lessons from our chat:

1. Comics can put kids in the driver's seat.

Françoise and her husband have extensive knowledge and appreciation of comics. It comes as no surprise that they read comics frequently with their children. As Françoise puts it, "When I was reading comics with both of them, I noticed it had all of the pleasure of reading a book with someone, having them on your lap and the physical closeness. But with the comics, the kids were actually in charge. They could follow the visual narrative. It's as if they were finally driving the car, as opposed to being in the passenger's seat."

This is to say that comics are uniquely understandable to many kids, even if they are not yet reading independently. The visual narrative is there, often in wordless panels, and kids can more easily follow and tell the stories they encounter. In Françoise's words, "Kids get so much from context. When we tell them, 'now you have to get stories from books,' by reading, we're narrowing their multi-modal learning down to one dimension. Comics are multi-dimensional." Like kids.

2. Kids aren't going to learn anything because we think it's good for them.

This lesson isn't a news flash for any parent! And yet, time and again, we nudge (push?) our kids to learn skills without sparking their interest first. Kids who are interested and curious are going to learn and retain more, and comics can be instrumental for new readers. As Françoise noted, all comics are not created equal. Even with this caveat, if a child is interested in reading comics, we should nurture that excitement for reading.

"I want my child to learn French," is not enough. But if a child is in a French immersion program, s/he will likely be incentivized to learn the language in order to communicate with new friends. How else will they communicate on the playground? This may be an extreme example, but smaller ones emerge daily. Your child might not be interested in longer fairy tales, but perhaps knowing that a fairy tale is the basis for Frozen, would inspire a request for reading "The Snow Queen." Or, like Françoise's husband, Art Spiegelman, says, "I learned to read because I wanted to know if Batman was a good guy or a bad guy!" We must put our kids' perspectives first, and focus on why they will want to acquire a new skill, in addition to how we can help facilitate the process.

In the case of comics and reading, Françoise urges parents to accept all forms of literature as acceptable for kids. Oftentimes teachers who offer comics in their classes hear feedback from parents that is akin to, "But I send my child to school to learn to read. Not to read comics!" And likewise, both teachers and parents should understand how to use this excitement about comics to build literacy. There are basic tools, as with any medium, that can make comics even more effective for teaching kids to read.

3. It is important to give kids a path to understand and control their emotions.

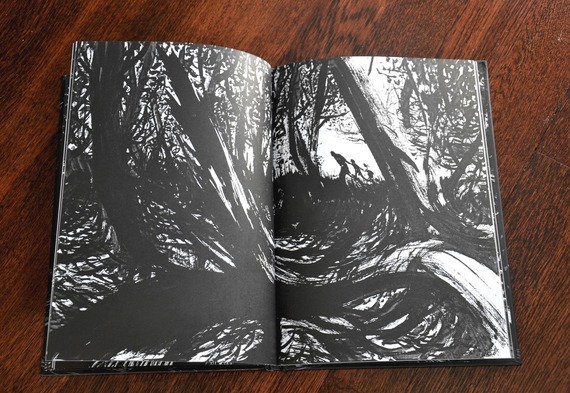

TOON recently released a new take on the classic story of "Hansel and Gretel," by Neil Gaiman and Lorenzo Mattotti. We discussed the role of fear in this frightening tale. Françoise noted that in a recent conversation with Neil Gaiman, he revealed that he heard the story when he was around four years old, and while it terrified him, it also helped him better "understand dark things when they show up..." and that you can fight back and beat dark things. "It's like an inoculation."

Françoise noted, "It is important to give kids a path to control their emotions, rather than pretending something will never happen." She used the earliest game of peek-a-boo as an example. Initially, infants are slightly scared that we have disappeared when playing this game. But after a short while, they grow to enjoy the thrill...and demand it repeatedly! We should provide pathways to understanding complex emotions as kids grow older, and give them the opportunity to explore these emotions in dialog with us.

When I suggested to Françoise that perhaps I would now read "Hansel and Gretel" to my son -- I had resisted before because he is only 4 -- she nodded, but also gave this very wise perspective, "This is why I'm so passionate about books. They last and have a long shelf life, and if you're raising kids, you know how quickly they change. But if you have books around, and if you read books with them and have the right book when they're ready. They will find it. You don't have to figure out the time schedule for them."

For more from Françoise about cultivating creativity in kids and other nuggets of wisdom, check out our full conversation here.

This was originally posted on Zoobean's blog.