By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

The Ethics of Documentary Filmmaking

To film or not to film? How close to a subject is too close? How far is too far? These are questions that documentary filmmakers should be asking themselves when they set out to record a true story. Sometimes lines are crossed, and sometimes boundaries are set beforehand. Sometimes the filmmaker and the audience disagree on where the line is, and a divide is created between them.

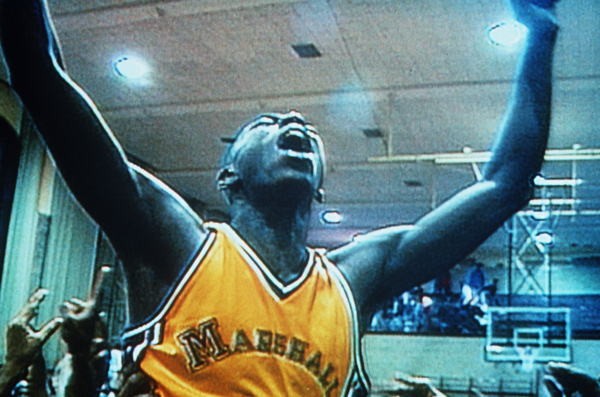

Filmmaker Gordon Quinn is in town at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival not only to celebrate a 20th anniversary screening of the hit film “Hoop Dreams,” which he co-produced, but to also present a masterclass on ethics in documentary filmmaking. Before the panel, Indiewire spoke with Quinn as well as other documentary filmmakers to get their take on ethical approaches and morally ambiguous boundaries.

Documentary filmmakers, Quinn said, need to have a sense of the ethical questions or concerns that will affect their work. It’s on a different scale than journalism, simply because doc filmmakers spend so much time with subjects, sometimes years, that they become deeply involved in the intimate aspects of their lives.

“We as documentary filmmakers, I feel, have a responsibility towards ethics,” said Quinn. “You owe your audience to tell the truth, to get to the bottom of the story, to be accurate in what you’re presenting.”

He brought up an instance on one of his films when a particular subject no longer wanted to be involved. He and his team held a meeting with the woman and explained that she could see the film before it was finished and express any concerns.

He brought up an instance on one of his films when a particular subject no longer wanted to be involved. He and his team held a meeting with the woman and explained that she could see the film before it was finished and express any concerns.

“We say this to everyone at the beginning, we say you’re going to see this film before it’s done. You can see it when it can still be changed. We’re going to try to convince you that we need you in this movie; that it’s important for the story that it’s good for society in general to tell this story, and why your part of it is so important. At the end of the day, if I can’t convince you we’ll take you out of the movie.”

Quinn then went on to explain that the rules that apply to an average person, might not apply to someone who is already famous.

“If they’re already famous, they already have agency in the world,” Quinn said. “We want to get the facts right of course, and if it’s really something that bothers you or that you’re not happy with, you’re going to be listened to. But at the end of the day it has to be my decision.”

Director James Keach and producer Trevor Albert are familiar with the aspect of documenting a celebrity, but they allowed themselves some limitations for “Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me,” their documentary on the country music star’s struggle with Alzheimer’s Disease.

Director James Keach and producer Trevor Albert are familiar with the aspect of documenting a celebrity, but they allowed themselves some limitations for “Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me,” their documentary on the country music star’s struggle with Alzheimer’s Disease.

“I don’t think there was anything that we didn’t want to shoot, Keach said. “I think in your choice lies your talent, and our choice was to always retain Glenn’s dignity and at the same time to not back away from the authenticity of the disease. Glenn did not want to back away from it either so it’s a balancing act.”

“Then it was a question of, how far do we go? How dark do we go?” said Albert. “I think the question about following somebody with a degenerative disease, when we started we had no idea where we were headed. We didn’t know how far and how fast it would progress. We just sort of found ourselves starting to follow this story.”

But at the end of the day, Keach said, “We set lots of limits. The limitations that we set were, and still remain, Glenn’s dignity and what his family would want and what his children would want.”

“Mugshot” director Dennis Mohr faced quite a different conundrum, as many of his subjects were no longer even alive.

“Mugshot” director Dennis Mohr faced quite a different conundrum, as many of his subjects were no longer even alive.

“Mugshot” examines the cultural significance of the criminal mugshot and asks whether the older of the photos (those whose subjects had long ago died) can now be considered art. As one can imagine, the subject of morality often came up as Mohr was making his film.

“The first thing that comes across your mind,” Mohr said, “is are you going to be putting up child molesters and heinous murderers, and all sorts of vile acts like that?”

However, when he sought out and spoke with many of the collectors featured in the film, most of them had already curated their collections out of those kinds of images. “They felt that that’s not something they wanted,” Morh said. “But, we did have to cover the fact that hey, these mugshots do contain heinous criminals.”

So what happens when subjects are not around to either defend themselves or support the film? That is the case with “Farewell to Hollywood,” co-director Henry Corra’s film about a teenage cinephile named Regina Nicholson who died at the age of 19.

Corra began making the film with Nicholson after meeting her at a film festival and agreeing to help her make a film before she died of cancer. “The mission is noble,” wrote our critic when he saw the film last year, “but the final, scrappy product contains an ethical dubiousness that slips between Nicholson’s apparent intentions and those of the much older man with whom she spent her dying days. Is it a provocation from beyond the grave or a misconceived paean from the surviving director?”

Corra was no doubt aware of the dubious concerns. “We did not have sex, OK?” he stated unprompted at the film’s premiere at IDFA. “That’s what everybody’s thinking right?”

Corra didn’t attend Hot Springs for the screening, but answered a few questions via email. He insisted on calling the film “Living Cinema,” a collaborative effort where the boundaries between subject and filmmaker and art and life are collapsed.”

“What do I say to people who think I crossed a line – overstepped boundaries?” Corra replied, “That’s a line created by you asking the question, I think. Reggie and I had a creative collaboration and friendship that was boundless. Art is supposed to be boundless and limitless. Art must cross lines so we can grow as people.”

Though Corra had denied a physical relationship with Nicholson, Quinn suggested that the fact that he even had to bring it up meant that Corra may have treated into questionable waters. “The glib version is don’t fuck the talent,” Quinn said. He hadn’t yet watched “Farewell to Hollywood,” but assured that sometimes filmmakers and subjects fall into unethical relationships or the filmmakers themselves make morally questionable decisions. “I often see things where I’m like, ‘I wouldn’t have done that’ or ‘I wouldn’t have been comfortable with that.’ These are hard questions you need to be asking yourself and that you need to pay serious attention to.”

Documentarians then must set their own rules, maintain their conscientiously established boundaries and avoid crossing lines set by both themselves and their subjects. Though they also must acknowledge that there may always be an audience member who questions whether or not something should have been filmed and deems it unethical.

READ MORE: What It’s Like to Be the Subject of a Documentary Film

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.