Inside the New School Lunch

Beef-loving Nebraskan kids are warming to veggie burgers and carrot sticks. Can the rest of the nation follow?

On a typical Thursday, Cole Coffey, a sixth-grader at Schoo Middle School in Lincoln, Nebraska, would face a school lunch menu that reads a little like a Weight-Watchers recipe guide:

WHOLE GRAIN CHICKEN NUGGETS WITH WHOLE WHEAT GARLIC BREAD

WHOLE GRAIN LASAGNA WITH WHOLE WHEAT GARLIC BREAD

SWEET & SOUR MEATBALLS ON WHOLE GRAIN BROWN RICE

Purists who claim it's a cultural crime to use a fibrous, nutritious substitute for the traditional Italian bruschetta may be even more dismayed by the day's vegetarian offering: "Veggie Wrap on Whole Grain Tortilla."

And, in this, one of the top meat-producing states in the country, there's also a fully stocked raw vegetable bar and a daily spinach salad.

The legumes and whole grains have arrived partly as a result of the 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. The law, supported by Michelle Obama and her "Let's Move" initiative, made aggressive changes to the school lunch program, requiring schools to switch all of their white grains to whole, to slash salt content, and to offer twice as many fruits and vegetables.

As the New York Times Magazine reported last weekend, the resulting criticism has whirred with the vigor of a thousand Vitamixes:

Republicans now attack the new rules as a nanny-state intrusion by the finger-wagging first lady. Food companies, arguing that the new standards are too severe, have spent millions of dollars lobbying to slow or change them. Some students have voted with their forks, refusing to eat meals they say taste terrible.

What has ensued is a food fight of Seussian tenor. Food manufacturing companies complain that the law's tomato paste measurements are unfair. An attempt by an Austin school district to move toward "Meatless Mondays" prompted an angry screed by the former Texas agriculture commissioner, Todd Staples. (In the Lone Star state, "we have no room for activists who seek to mandate their lifestyles on others," he wrote). One student's photo of two slices of lunch meat, raw cauliflower, and crackers on a sad styrofoam tray recently whipped up a back-in-my-day furor in Oklahoma.

The School Nutrition Association, the school food vendors' lobby, says student participation in the school lunch program has plummeted, and that schools are reporting devastating declines in lunch revenue. Perhaps most importantly, studies found that kids, though forced to take the fruit in line, were throwing them away without taking a single bite.

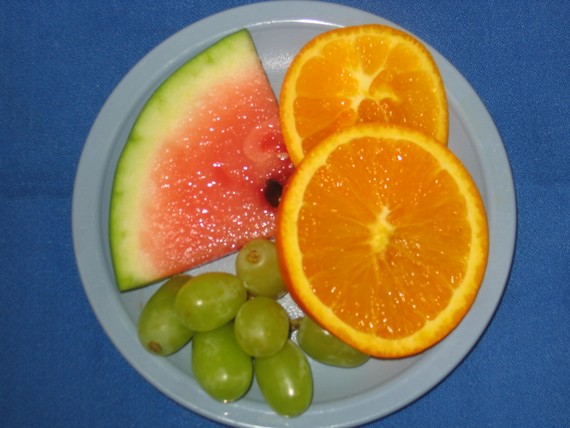

But not, apparently, in Lincoln, Nebraska. The Lincoln public school system has gone above and beyond the legal requirements, dishing out a daily vegetable smorgasbord. On top of veggie burgers and black-bean chili, the school system serves up local yellow watermelons, black and green peppers, cherry tomatoes, blueberries, ripe plums, and fresh cantaloupe. It was enough to earn the district a "Golden Carrot Award" from the Physicians Committee, a nonprofit medical organization of 12,000 doctors.

The students' reaction? So far ... not too bad, says Cole's mother, Jessie Coffey, who works on wellness issues for the district and sent these photos of the students' new lunch options.

The biggest change, she said, was making all of the breads and pastas 100 percent whole grain, as well as offering at least two fruits and vegetables every day, rather than one.

During the short fall and spring growing seasons, the district tries to capitalize on local produce, bringing in peaches, plums, nectarines, and melons. In the winter, it's canned fruit and frozen berries.

At the secondary schools, there's a vegetable bar with 10 choices—a big hit with independent-minded teens. At least in Lincoln, school officials sigh, school-lunch participation hasn't dropped like it has in other cities.

It hasn't all been smooth snacking, though. Two years ago, the middle school cut its portion sizes, so students went from getting three breadsticks to two. "It was very noticeable that it was less," Coffey said. "They were hungry, because in middle school, eating fruits and vegetables isn’t cool. We said, 'Make sure you’re taking the fruits and vegetables. You could have an apple, salad, and green beans.'"

The bitter greens in the daily spinach salad were dialed up more gradually. The salad started at 75 percent iceberg, 25 percent spinach, but now the proportions are reversed. "Now the kids don’t like it as well," she said. "It’s offered every day, the kids just get tired of it. A lot of kids take the salad and just throw it away. That’s one of the bigger national issues."

A vegetarian option is available daily, and about a quarter of students eat it. (When they like what's on offer, that is.)

The bigger firestorm hasn't been over the healthier lunches, but about another guideline recently put in place: Parents are now discouraged from bringing cupcakes for classroom birthday parties. (It's an allergy issue.)