In which something old and powerful is encountered in a vault

FINGERS stroke vellum; the calfskin pages are smooth, like paper, but richer, almost oily. The black print is crisp, and every Latin sentence starts with a lush red letter. One of the book’s early owners has drawn a hand and index finger which points, like an arrow, to passages worth remembering.

In 44BC Cicero, the Roman Republic’s great orator, wrote a book for his son Marcus called de Officiis (“On Duties”). It told him how to live a moral life, how to balance virtue with self-interest, how to have an impact. Not all his words were new. De Officiis draws on the views of various Greek philosophers whose works Cicero could consult in his library, most of which have since been lost. Cicero’s, though, remain. De Officiis was read and studied throughout the rise of the Roman Empire and survived the subsequent fall. It shaped the thought of Renaissance thinkers like Erasmus; centuries later still it inspired Voltaire. “No one will ever write anything more wise,” he said.

The book’s words have not changed; their vessel, though, has gone through relentless reincarnation and metamorphosis. Cicero probably dictated de Officiis to his freed slave, Tiro, who copied it down on a papyrus scroll from which other copies were made in turn. Within a few centuries some versions were transferred from scrolls into bound books, or codices. A thousand years later monks meticulously made copies by hand, averaging only a few pages a day. Then, in the 15th century, de Officiis was copied by a machine. The lush edition in your correspondent’s hands—delightfully, and surprisingly, no gloves are needed to handle it—is one of the very first such copies. It was printed in Mainz, Germany, on a printing press owned by Johann Fust, an early partner of Johannes Gutenberg, the pioneer of European printing. It is dated 1466.

Some 500 years after it was printed, this beautiful volume sits in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, its home since 1916. Few physical volumes survive five centuries. This one should last several more. The vault that holds it and tens of thousands of other volumes, built in 1951, was originally meant to double as a nuclear-bomb shelter.

Although this copy of de Officiis may be sequestered, the book itself is freer than ever. In its printed forms it has been a hardback and, more recently, a paperback, published in all sorts of editions—as a one off, a component of uniform library editions, a classic pitched at an affordable price, a scholarly, annotated text that only universities buy. And now it is available in all sorts of non-printed forms, too. You can read it free online or download it as an e-book in English, Latin and any number of other tongues.

Many are worried about what such technology means for books, with big bookshops closing, new devices spreading, novice authors flooding the market and an online behemoth known as Amazon growing ever more powerful. Their anxieties cannot simply be written off as predictable technophobia. The digital transition may well change the way books are written, sold and read more than any development in their history, and that will not be to everyone’s advantage. Veterans and revolutionaries alike may go bust; Gutenberg died almost penniless, having lost control of his press to Fust and other creditors.

But to see technology purely as a threat to books risks missing a key point. Books are not just “tree flakes encased in dead cow”, as a scholar once wryly put it. They are a technology in their own right, one developed and used for the refinement and advancement of thought. And this technology is a powerful, long-lived and adaptable one.

Books like de Officiis have not merely weathered history; they have helped shape it. The ability they offer to preserve, transmit and develop ideas was taken to another level by Gutenberg and his colleagues. Being able to study printed material at the same time as others studied it and to exchange ideas about it sparked the Reformation; it was central to the Enlightenment and the rise of science. No army has accomplished more than printed textbooks have; no prince or priest has mattered as much as “On the Origin of Species”; no coercion has changed the hearts and minds of men and women as much as the first folio of Shakespeare’s plays.

Books read in electronic form will boast the same power and some new ones to boot. The printed book is an excellent means of channelling information from writer to reader; the e-book can send information back as well. Teachers will be able to learn of a pupil’s progress and questions; publishers will be able to see which books are gulped down, which sipped slowly. Already readers can see what other readers have thought worthy of note, and seek out like-minded people for further discussion of what they have read. The private joys of the book will remain; new public pleasures are there to be added.

What is the future of the book? It is much brighter than people think.

ALMOST as constant as the appeal of the book has been the worry that that appeal is about to come to an end. The rise of digital technology—and especially Amazon, a bookshop unlike any seen before—underlined those fears. In the past decade people have been falling over themselves to predict the death of books, of publishers, of authors and of bookshops, even of reading itself. Of all those believed at risk, only the bookshops have actually suffered serious damage.

Historically books were a luxury item. Having become cheap enough for the masses in the 20th century, in the 21st century digital technology and global markets have made them more accessible still. In 2013 around 1.4m International Standard Book Numbers (ISBNs) were issued, according to Bowker, a research firm, up from around 8,100 in 1960. Those figures do not capture the many e-books that are being self-published without an ISBN.

Many of those self-published books are ones in which traditional publishers would have had no interest, but which almost-free distribution makes worthwhile: do you feel like checking out some Amish fiction? The size of the text, as well as the size of the niche, becomes less of an issue, too; short stories and novellas are making a comeback. “Before there used to be too-big-to-carry and too-short-to-print,” says Michael Tamblyn, the boss of Kobo, an e-reading company. “Now all those barriers are gone.”

Even the most gloomy predictors of the book’s demise have softened their forecasts. Nicholas Carr, whose book “The Shallows” predicted in 2011 that the internet would leave its ever-more-eager users dumb and distracted, admits people have hung onto their books unexpectedly, because they crave immersive experiences. Books may face more competition for audiences’ time, rather as the radio had to rethink what it could do best when films and television came along; the habit of reading for pleasure has fallen slightly in the past few years. But it has not dropped off steeply, as many predicted. The length and ambition of a bestseller such as Donna Tartt’s “The Goldfinch”—864 pages in paperback—shows that people still tackle big books.

And they are willing to cart them around, too. The much ballyhooed decline of the physical book has been far from fatal. “I thought everything was going to change so much more quickly and so much more radically,” says Ellie Hirschhorn, chief digital officer at Simon & Schuster, a big publisher, who had predicted in 2010 that half of all book sales would be e-books by 2013. Instead, last year e-books accounted for around 30% of consumer book sales (not including professional and educational books) in America, the largest book market in the world and the country where e-books took off most quickly. In Germany, the world’s third-largest, e-books were around 5% of consumer book sales last year, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers, a consultancy. The growth rate of e-books has recently slowed in many markets, including America and Britain. Publishers now expect most of their sales to remain in print books for decades to come—some say for ever.

There are a number of reasons. One is that, as Russell Grandinetti, who oversees Amazon’s Kindle business, puts it, the print book is “a really competitive technology”: it is portable, hard to break, has high-resolution pages and a “long battery life”. Technology companies that are used to consumers flocking to snazzy features and updates have found it surprisingly challenging to compete with a format of such simplicity, and consumers are uninterested in their attempts to do so. All most want is the ability to change font size, which is attractive to older eyes. Experiments with reinventing the presentation of books—by embedding sound and video inside e-books, for example—have fallen flat. Sales of e-readers, the most popular of which is the Kindle, are in decline. “In a few years’ time,” a recent report by Enders Analysis, a research firm, predicts, “we will look back at e-readers and remember them as one of the shortest-lived of all consumer media devices.”

You do not need a dedicated e-reader to read an electronic book. The multipurpose tablet devices which are replacing e-readers let you read books and—crucially—buy them whenever you like. Some forms of book benefit a lot. Heavy readers of genre fiction—romance, thrillers and science fiction—were early converts to the cheaper, more portable alternative. Other sorts of book have remained more stubbornly in print form, for various reasons. Physical books make better gifts; many people still want bookshelves in their homes. Parents who feel that their children are spending too much time with screens go for printed books as an alternative, which means a new generation is growing up in contact with print.

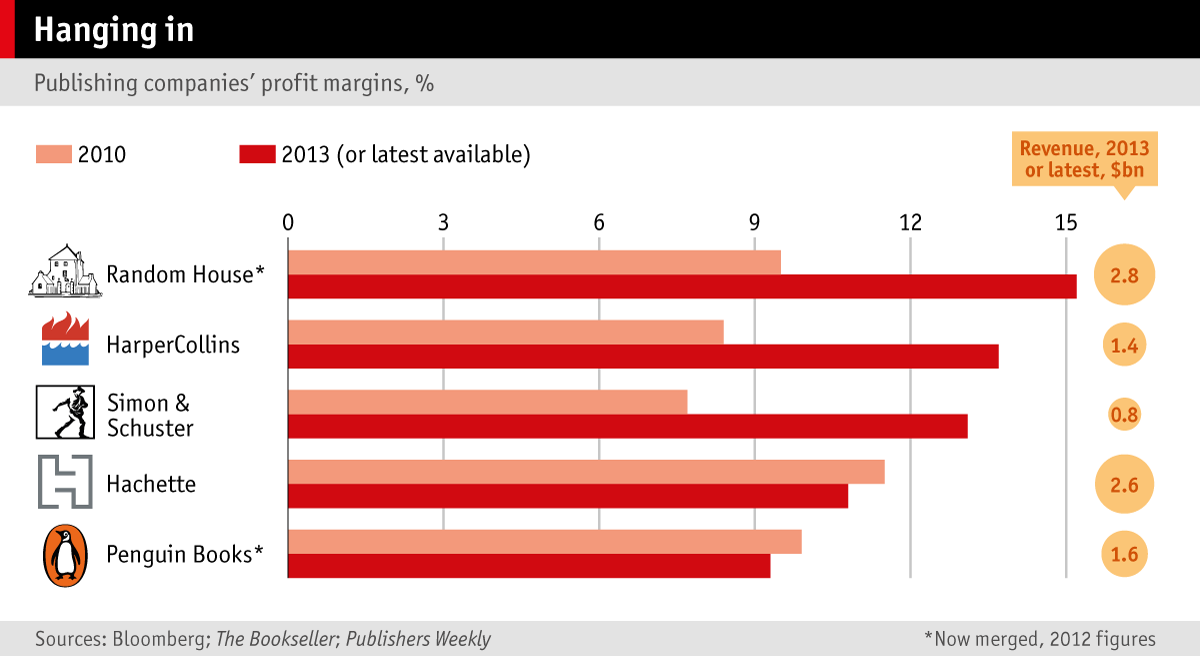

Perhaps more unexpected than the flourishing of the book is the health of some publishers. When the music and newspaper industries were ravaged by the internet over a decade ago people feared the same fate would befall publishing. “I thought I would say to people, ‘I’m what used to be called a book publisher’,” says Dominique Raccah, the boss of Sourcebooks, an independent publisher. But the volume of book sales has stayed steady, and publishers are still, for the most part, the people producing the books that sell. Revenues are down slightly because e-books are a significant part of the market and their prices are lower; but costs have fallen, and thus profits are still there to be made.

Publishers used to guess how many books to print and ship and then pay for unsold copies to be returned to them—sometimes as much as 40% of the print run. Print-on-demand systems—digital technology at the service of physical books—reduce risks by enabling publishers to print smaller batches and then fire off more copies quickly if a book sells well. This has proved especially helpful for smaller publishers, such as university presses, says John Ingram of Ingram Content Group, a book distributor.

Analogies with the music and newspaper businesses have proved flawed. The music business collapsed in part because the bundle it was peddling fell apart: people wanted the right to buy one song, not the whole album. Books are not so easily picked apart. The music business also suffered because piracy was so easy: anyone who buys a CD can extract the music it contains in digital format in seconds, and can then share it online. Creating a digital file from a printed book by scanning each page, by contrast, is a nightmare. The fate of newspapers has been driven by the decline of advertising—a business publishers (which sell books to readers, not readers to advertisers) were never in.

Where the publishers do their selling, though, is changing a lot. The biggest change of the past decade is the decline of physical bookshops, which is good neither for publishers nor the booksellers whose doors have closed. Borders, a chain of American book shops, and Weltbild, a German one, have gone under. The change affects which books have a chance of breaking out: bestsellers flourish, but midlist books that might have been discovered while browsing in a bookstore are worse off, because consumers cannot easily stumble upon them while shopping on the internet. To continue to bring in customers bookshops have changed their look, and increased the space they assign to nonbook products, like stationery, cards and other gifts. “A bookstore is defending a very specific lifestyle, where you want to take time out of your day and write or think or read,” says Sarah McNally, owner of a bustling independent bookshop in Manhattan.

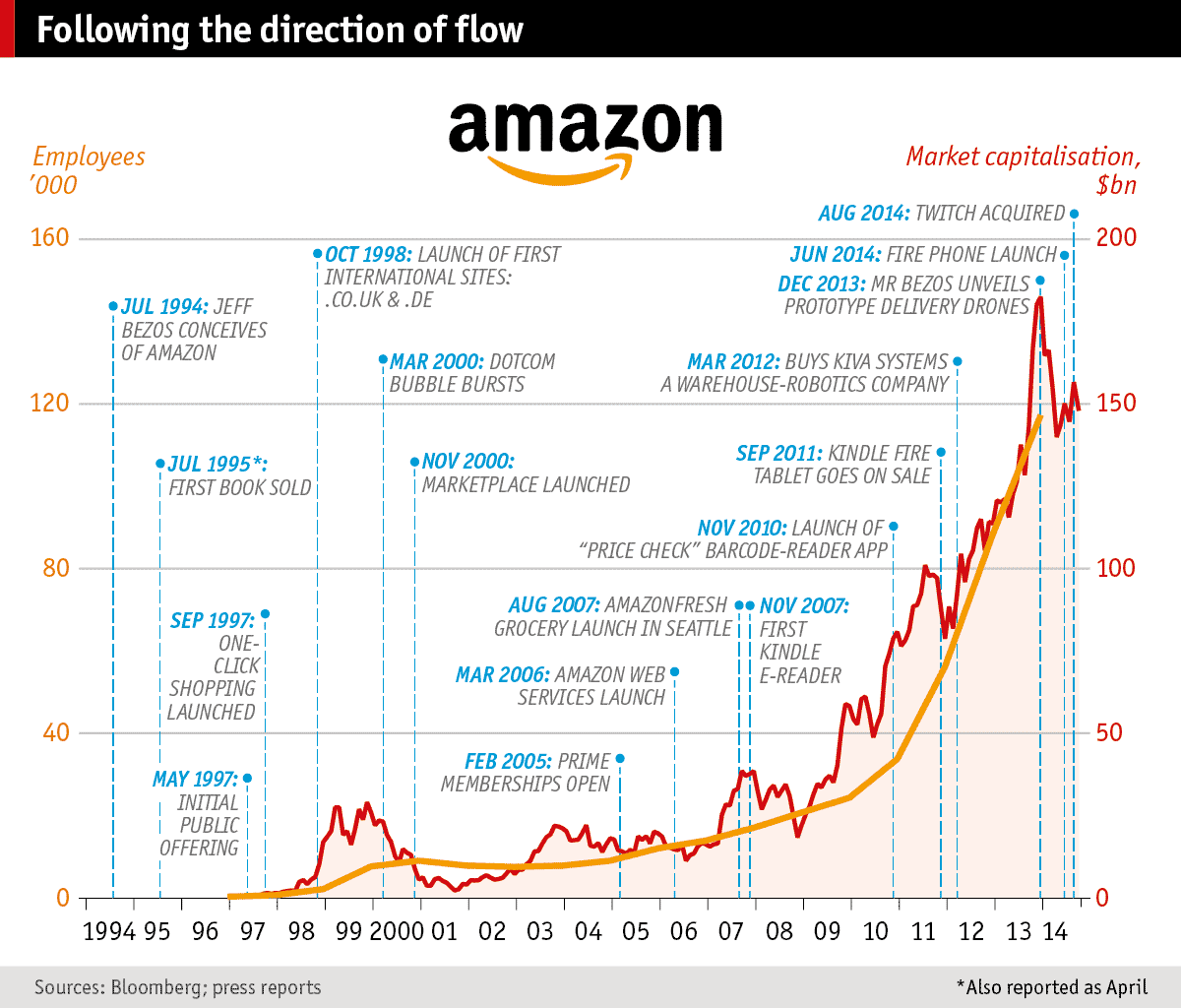

There have been two casts of villain. First came the large chain stores in the 1980s that wounded independent booksellers and put many out of business. More recently Amazon, an online retailer that started with books in 1999 and now claims to sell “everything”, has ensured an ongoing wave of closures. Amazon is believed to control nearly half of total book sales and around two-thirds of e-book sales in America. In Britain its grip on the e-book market is even stronger. Booksellers and publishers see Amazon as similar to the enormous polar bear in the television show “Lost”, trampling through the tropical rainforest devouring victims at random.

Amazon is no devotee of literature. It sees books as a “gateway” commodity it can use to attract customers. It has squeezed publishers and muscled out other booksellers by discounting books and selling some below cost. Recently Amazon has been waging a very public, months-long war with Hachette, a large publisher, in which it has in the eyes of many abused the power that its market dominance provides in an attempt to squeeze Hachette’s profits and drive prices even lower. Already the average amount American consumers say they paid for a book (averaging both print and e-books) has declined around 40% since 2009, from $15.45 in 2009 to $9.31 last year, according to Nielsen, a research firm.

The book industry rightly feels torn between resenting Amazon for its dominance and its mercenary attitude towards books, while relying on the company for business and appreciating that it has made books more accessible to buyers. “They really are evil bastards,” Anthony Horowitz, an English novelist, has said about Amazon. “I loathe them. I fear them. And I use them all the time because they’re wonderful.” And it has opened the doors for a hurried rush towards self publishing.

BEFORE the 19th century it was common for writers to publish themselves, a practice that carried no particular stigma, but imposed a significant burden of inconvenience on seller and buyer alike. One author in Paris had to direct buyers to his home on “Mazarine Street...above the Café de Montpellier, on the second floor using the staircase on the right, at the far end of the alley”. As publishing became a mass-market business in subsequent centuries, the self-published came to be seen as kooks or egotists, and treated as marginal in either case. Readers went to bookshops, bookshops bought from publishers and that was the way it was. Bookshops mostly refused to stock them.

Advertisement

Today self publishing has made a comeback. The internet enables people to sell their e-books and print books without the hassle of directing people to their homes or trying to get bookstores to display them. It also offers them success on a scale never before possible.

At last spring’s London Book Fair there was a booth rented by eight authors who said that, between them, they had sold a staggering 16m books and spent weeks on the New York Times bestseller list—all without the help of a traditional publisher. They are used to having their claims dismissed; Bella Andre, a self-published romance writer with an economics degree from Stanford, got so irked when a publisher challenged her heady sales figures that she took a picture of a bank statement and sent it to him. “No one is counting our books in any survey that comes out in the media,” sighed Barbara Freethy, another romance writer. She says that, as of September, she has sold over 4.8m books.

To write a book costs nothing but time. To hire an editor, cover designer, formatter and publicist can, if you think them necessary, be done for $2,000 or less. Amazon will publish and sell the resultant e-book to any of its 250m customers who may be interested; smaller sites will do the same, and many offer print-on-demand sales, too. Authors who self publish an e-book through Amazon get up to 70% of net sales, as opposed to the 25% they might get on an e-book that went through a publisher.

Last year Amazon’s sales of self-published books were around $450m, according to one estimate; a former Amazon executive thinks the number is higher. In America about a quarter of the books that got an ISBN in 2012 were self-published, according to Bowker—almost 400,000 titles. In 2013 self-published books accounted for one out of every five e-books purchased in Britain, according to Nielsen.

“Wool” started off as a short story online about a subterranean city called the Silo. Reader enthusiasm and feedback encouraged its author, Hugh Howey, to extend it into a novel. More enthusiasm followed. Simon & Schuster, a big publisher, did an unusual deal to license rights to the print book, while Mr Howey continued to sell the e-book off his own bat. It became a bestseller and may become a film. The film of “Fifty Shades of Grey”, the poster-child for online fiction, hits cinemas next year. Like “Wool”, E.L. James’s “Fifty Shades...” started off online, and some of its e-book success has been attributed to the fact that reading erotica is more discreetly done on a tablet. But since being acquired by Random House it has done remarkably well in its printed form, too. All told, it and its two sequels have chalked up sales of over 100m worldwide.

Video

Like Ms James, most writers still sign with publishers when they have the chance, because print books remain such a sizeable chunk of the market. But the self-publishing boom is changing how those publishers work. Self-published authors attract readers by selling their books for just a few dollars and are aggressive about offering promotions to boost sales. This puts pressure on publishers’ prices—especially in genre fiction, where self publishing is most powerful. In the past five years the revenues of Harlequin, a publisher of romantic fiction, have dropped by around $100m; in May it was purchased by HarperCollins.

As well as changing what publishers can charge for some types of book, self publishing also changes how they go about finding them. Publishers hoping to spot the next hot thing have started to scour online writing sites, such as Wattpad, where people receive feedback on their work from other users. Any interest they show is normally warmly appreciated. In the past 12 months the average earnings for self-published authors have probably been around $1,180, reckons Mark Coker, the boss of Smashwords, a self-publishing platform, with most of them getting less than that. Such authors find themselves highly dependent on Amazon’s recommendation system and websites that offer promotions to boost their sales; most readers still gravitate to books that have been professionally written, edited and reviewed.

But the advantages of being “properly published”—editors, promotion, and the like—should not be oversold. “We have to be careful not to compare the reality of self publishing with the ideal of legacy publishing,” says Barry Eisler, a thriller writer. In 2011 he walked away from a publisher’s advance of $500,000 in favour of the self-publishing route; he says the decision paid off well. Susan Orlean, an author and a staff writer at the New Yorker, considered something similar for a recent book. “In a million years I would have never thought of that before,” she says. She thinks the day will come when publishers may have to start unbundling their services. “The mere fact that publishers make hardcover books won’t be a powerful enough argument. They will have to reimagine their role.” Publishers could start offering “light” versions of their services, such as print-only distribution, or editing, and not taking a cut of the whole pie.

Publishers realise that they have to change. “Publishers will only be relevant if they can give authors evidence that they can connect their works to more readers than anybody else,” admits Markus Dohle, who runs Penguin Random House, the world’s largest consumer-book publisher.

Such connection is crucial, because the same technology that is making it easier for people to publish their own books is also making it easier for them to explore new ways of finding, sharing, discussing and indeed emulating the books of others. (Ms James’s “Fifty Shades of Grey” started off as fan-fiction based on the characters of Stephenie Meyer’s bestselling “Twilight” books.) From online reviews to the world’s numerous literary festivals to all sorts of social media, writers are ever more aware of and available to their audiences. Ms Orlean says she was used to “writing into the void”, but now posts regularly about what she is working on. For her and others the contact seems like an opportunity. Others find it irksome. Most, probably, see it as a bit of both. But it is not going away. And it is not entirely new.

In Cicero’s day authors ready to launch their newest work would gather their friends at home or in a public hall for a spirited recitatio, or reading. Audiences would cry out when they liked a particular passage. Nervous authors enlisted their friends to lend support, and sometimes even filled seats with hired “clappers”. They were keenly aware of the importance of networking to get influential acquaintances to recommend their works to others. The creation of books started off as something both personal and social; the connection embodied in that dual nature is at the heart of what makes books so good at refining and advancing thought. It was just that the practicalities of publishing in the printing-press age made the personal connections a bit harder to see.

THOSE whose tastes do not run to the dystopic “Wool” or the embondaged “Fifty Shades...”, who fear that nothing good can come of readers asking authors anything on Reddit and that Flaubert was well-served by his lack of Facebook friends, will find a kindred spirit in Niccoló Perotti. In 1471 the humanist scholar complained to a friend, “Now that anyone is free to print whatever they wish, they often disregard that which is best and instead write, merely for the sake of entertainment, what would be best forgotten, or better still, be erased from all books.” His worries were echoed for centuries. “If everyone writes, who will read?” asked Christoph Martin Wieland, an 18th-century German writer.

As new means of production, new means of distribution and new audiences have grown up hand in hand throughout the modern history of the book, they have always been looked at askance by representatives of the old order. This may be why novelties have often been slow to take over. Scrolls continued to be used for hundreds of years after the codex was developed. Early printed books tried to diminish the shock of the new by looking like handwritten manuscripts, rather as e-books have, to date, aped print.

But as printers grew in ambition they experimented with ways to make new sorts of “book” that could do things the old ones could not. The ability to mass produce short pamphlets easily and cheaply led to the creation of Flugschriften, or “flying writings”, such as those penned by Martin Luther; these pamphlets were purchased by people who had never been able to afford a book. Printers gradually pushed into other new genres with no history: almanacs that would forecast weather patterns, chapbooks containing folk tales.

In the 19th century stereotyping, which allowed for whole sheets to be set at once, gave publishers the opportunity to reach new populations of readers through magazines and newspapers and also to expand the world of book-buyers. Their “Yellowbacks” (in Britain) and dime novels (in America) started off as affordable reprints of older books, not least because that meant not having to pay authors. But in time the publishers came to experiment with new types of content that reflected readers’ interests and demography, such as Westerns and guides to practical knowledge. A similar pattern arose with the introduction of affordable and portable paperbacks in the middle of the 20th century.

Experiments with form have been complemented by experiments with business models. Publishers in the 17th and 18th centuries often sold books by “subscription”, which meant that consumers would agree in advance to buy a book after seeing a prospectus. It acted as a market test. If not enough people were interested, the project could be dropped.

In the 18th century another new model arose in Britain, tailored to the needs of a literate class that wanted to read more than it wanted to buy: “circulating libraries” sold annual memberships that allowed readers to always have a book on the go. The most powerful of them, Mudie’s, was the Amazon of its day in terms of market power, says Leah Price, a professor of English at Harvard University. It would often buy up as much as half of a book’s print run for its network of borrowers; if Mr Mudie chose not to stock an author’s book, it could become an immediate dud. The circulating libraries’ business model encouraged publishers to put out books in three volumes, so three people could be reading one book at once; novelists would write to the form, fleshing out their prose to fill the “triple-decker” format. The development of magazine and newspaper serialisation further encouraged some novelists towards length, as well as setting up a distinctive rhythm of cliffhangers at the end of each instalment.

People tend to think of new genres as inferior to those that preceded them. Novels were particularly popular among circulating libraries’ patrons, much to the chagrin of the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who harrumphed that he “dare not compliment their pass-time, or rather kill-time, with the name of reading”. But history has been kinder to Walter Scott’s triple-deckers and the serialised doorstops of Alexandre Dumas, as it has to self-published oddities such as Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” or Marcel Proust’s “Swann’s Way”. Publishing technologies have replaced each other; business models have come and gone. But the various forms of book that have been encouraged along the way have almost all, like the texts of the greatest themselves, persisted.

OF THE various ways in which technology is expanding what a book can be, one of the most successful so far has been to add to books something that children have enjoyed for ever, and that most people required until the 20th century: another person to do the reading. The cost of recording audiobooks has fallen from around $25,000 in the late 1990s to around $2,000-3,000 today, says Donald Katz of Audible, an audiobook firm owned by Amazon. Books that lend themselves to performance or seek to inculcate self-improvement do particularly well as readings; commuting provides a perfect time for partaking of them. Audible, which is headquartered in New Jersey, says it is the largest employer of actors in the New York area. They do their spirited recordings from texts read off iPad screens—which they prop up on piles of books.

Information technology could provide new ways of getting words from the page to the brain, as well as old ones. Spritz is an application which beams words to a reader one at a time. Like a treadmill, readers can set their own speed and read more quickly, because their eyes can stay in one place instead of scanning a page. Its most immediate application is to allow longish texts to be read on smallish screens, such as those of watches. However Frank Waldman, Spritz’s boss, thinks people will consume whole books this way, as well as poetry, allowing poets to set their poem’s cadence for readers. (You can use spritz to read this chapter »)

The syncopated spritzing of sonnets and sestinas may or may not turn out to be a big hit; but new sorts of book that use the capabilities of technology for more than just recreating pages are, in time, a sure thing. And so is the decline, even possibly the demise, of some old sorts of book. Matt MacInnis of Inkling, an e-book company, says that the key question is “What are the things books used to do for us that software will now do for us?” Presenting people with procedural information they need in order to take on a simple task or fulfil a well-stated goal is one of those things. Books that simply tell people how to fix their Toyota, how to cook tarte tatin or how to find a place to stay in Tokyo would seem to have a limited future unless they can become objects that meet aspirational, not just informational, needs. On the other hand, books which actually teach, rather than simply inform, could have a very bright future, their pedagogy enriched by embedded media and software that adapts them to the user’s pace and needs.

And if publishers find that some sorts of book no longer make money, they will be able to do a better job selling the ones that do thanks to the far greater amounts of data that can be gathered when books are sold on the internet or read in electronic form. HarperCollins, for example, has found that when it discounts backlist books, around 10% of consumers buy another title from that author. “That’s information we never had before in the print world,” says Brian Murray, the boss of HarperCollins. Another big publisher is experimenting with “dynamic pricing” on around half of its e-books.

Data can also help decide what sort of content to acquire, particularly in the fields of academic, business and science publishing. Safari Books Online, a sort of database for book content owned by O’Reilly Media, uses data about subscribers’ reading habits to improve its offerings in this way. And Amazon has a trove of data about how people read, including how much time they spend on each page and when they abandon books. As yet, publishers do not have much access to these data; Amazon keeps them to itself. If or when publishers gain more, and start to think about them more deeply, data may be one of the aspects of the electronic world that change their business most.

This may not be to the advantage of authors seeking to make a living at their trade. One of the reasons dud books get published is that no one is quite sure what will sell. Publishers spread their bets on the basis of instinct, taste, friendship, hunches and stubbornness—for all of which a more data-rich world has less room. While there will be more books, there may be fewer people who can make a full living as writers and publishers, says Mike Shatzkin, an industry analyst.

This too could in part be seen as a return to previous eras, when people did not expect to earn a living by writing books, but used books as a means to advance their career or as a creative outlet. It is clear that most self-published authors are not doing it for the money they can reasonably expect to get—they are doing it to leave a mark, if only a digital one. Those who make a living too may increasingly be the ones who become marketable personalities online, on the festival circuit and elsewhere, rather than being just faded pictures on the inside back cover.

And writers who are not also performers may find that new opportunities arise. People with an idea for a book they cannot afford to take the time to write no longer have to go to a publisher. They can offer something like old-fashioned subscriptions to prospective readers, either on generalist crowdfunding sites, such as Indiegogo, or through specialist firms such as Pubslush and Unbound. Many will not get funded; some will succeed beyond their dreams. In February a young woman raised $380,000 through Kickstarter for “Hello Ruby”, a children’s book that teaches programming skills. Some will go on to greatness. Unbound, founded in 2011, has already helped produce a novel, Paul Kings north’s “The Wake”, which was long listed for the 2014 Man Booker prize in fiction.

Such funding is just another way in which the functions previously all wrapped up in publishing are being unbundled, and in which books are becoming more social. Those who use e-reading devices can see which passages were highlighted by other users, and there is talk of expanding offerings so people can discuss books in the margin at the same time. Bob Stein of the Institute for the Future of the Book predicts that some e-books will start to be sold with a “gloss” of commentary from their authors or other well-known critics, sort of like the director’s cut version of films.

There will be new experiments in storytelling, new genres born of the electronic age, and new authors who never would have been discovered in a print-only world. But there will also go on being lots of books in print—many of which may be more pleasant to hold, feel and own than ever before. In the face of the e-book there is “an imperative now to make the entire physical package itself special”, says Scott Moyers, an editor at Penguin Press. At the extreme is Arion Press, which sells sumptuous copies of classics that have been printed on letterpresses. Its two-volume Don Quixote with goatskin binding and lush illustrations sets readers back a bit more than $4,000.

Books will evolve online and off, and the definition of what counts as one will expand; the sense of the book as a fundamental channel of culture, flowing from past to future, will endure. People may no longer try to pass on wisdom to their sons and daughters through slave-written scrolls, as Cicero did in de Officiis, or even in print. It may even be that Voltaire was right, and that none of them will ever write anything more wise than what was set down 2,000 years ago. But it will not be for want effort, or of opportunity, or of an audience of future readers ready to seek out wisdom in the books that they leave behind.