Today’s White Paper for Schools contained two measures of its success.

By 2030, its ambition is that:

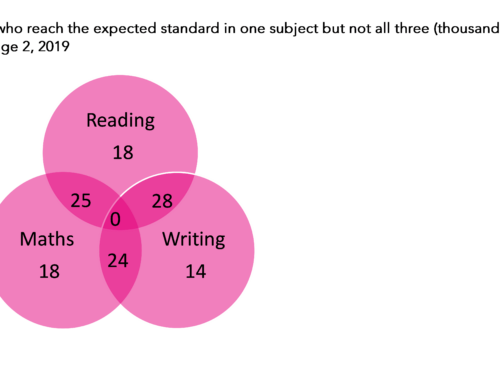

- 90% of pupils will achieve the expected standard in reading, writing and maths (up from 65% in 2019)

- The average grade in GCSE English language and maths will increase to 5 (up from 4.5 in 2019)

We previously looked at the implications of the Key Stage 2 target here.

The GCSE target is somewhat curious as this is not a measure that has hitherto been included in published Key Stage 4 statistics.

Although the White Paper references the 2019 Key Stage 4 Statistical First Release as the source of the 4.5 statistics, I cannot seem to find it. Most measures of attainment in English, including the Attainment 8 English score and the EBacc English score, are a composite measure of attainment in English language and English literature. In the days prior to the introduction of 9-1 grades, we found that this increased English scores by a third to a half of a grade compared that just using English Language.

(Updated 29th March. DfE subsequently published a methodological document outlining how the average grade in English language and maths could be calculated from published sources).

The current statistical first release already contains two composite English and maths indicators: the percentage of pupils achieving grade 4 or above, and the percentage achieving grade 5 or above, in both English and maths. Again, English is the highest of language and literature.

Prior to the reforms of GCSE, which saw the introduction of 9-1 grades, grade C (equivalent to grade 4) was considered the expected standard for 16 year olds. As John Jerrim wrote here, changing the expected standard to grade 5 brought it more in line with the international average in PISA. 43% of pupils achieved this standard in English and maths in 2019.

This raises the question of why the Department for Education has chosen to include in the White Paper a measure based on the average grade in English language and maths rather than the more familiar threshold measure based on grade 5 English (language or literature) and maths.

It suggests that it is trying to improve attainment across the attainment distribution, rather than focusing in one part of it. It also signals that it is downplaying attainment in literature from its attainment statistics for GCSE English. The Key Stage 2 target also aims to improve attainment in lower-performing areas by a greater margin but this is absent from the GCSE target.

According to published DfE statistics, 97.3% of pupils in state-funded schools entered GCSE maths in 2019 and the average grade was 4.53.

In 2021, the year of teacher assessed grades, the average grade increased to 4.9.

We know that results this summer will be lower than last year but more generous than 2019 as Ofqual try to return to pre-pandemic standards by 2023.

This then raises the question of comparable outcomes, the process through which Ofqual tries to maintain grading standards from one year to the next. Part of the process uses statistical predictions to set an indicative grade distribution that is comparable from one year to the next and from one exam board to another.

This sometimes leads to (perhaps unfair) criticism that grade distributions are fixed. This would certainly be a problem for the White Paper target if it were true. However, and in principle, grades can increase (or fall) if there is evidence of an increase in standards. This could include the National Reference Test in English and maths or senior examiner judgment.

So assuming that GCSE attainment falls back to 2019 levels in 2023, DfE is giving itself to 2030 to achieve results in GCSE maths that were slightly higher than in 2021. However, it will be with a cohort (currently in Year 3) that have had two of their early years of schooling disrupted by the pandemic.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment