Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles has been a ghetto for the impoverished, marginalised and substance-addicted for a century. This small neighbourhood has a homeless population of about 4,500 and a fearsome reputation as the place you end up when you hit rock bottom. Perhaps surprisingly, it also has an early morning running club. As the sun rises and turns the sky pink, the group can be seen bobbing past the tents and supermarket trolleys of personal effects, offering a glimmer of hope.

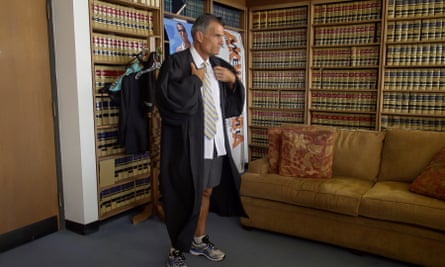

The Skid Row Running Club meets three times a week at 5.45am and members include recovering addicts and local workers. Rain or shine, the club’s leader, a judge called Craig Mitchell, will be among them – a pillar of strength, empathy and community-mindedness, and the star of a rousing new documentary, Skid Row Marathon.

The film charts the progress of club members such as Ben Shirley, who made a dizzying descent from promising heavy-metal musician to Skid Row alcoholic. He came to LA in 1990 with, he says in the film, “a signed band, working with a monster producer. I got to meet all my heroes, everything I’d wanted – and I’m not happy.” Soon, he was getting the DTs. One day, he says: “I totalled three cars on the way to the liquor store.” He was arrested, “then got out of jail and drank as much as I could, just hoping to die”. On his early outings with the club, he barely has enough puff to run, but he keeps showing up (vaping furiously before and after) and gains the confidence to go after his dream: to study at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Fellow Skid Row runners David Askew, a gentle soul whose former life as a crack addict is hard to imagine, and Rebecca Hayes, whose heroin and alcohol dependency led to her sleeping rough with a young son, also start to get back on their feet, fortified by the camaraderie, structure and physical exercise the club provides.

The powerful impact of exercise on people in recovery is well documented, with research uncovering complex ways in which, beyond endorphin highs and boosts to fitness, it helps reset the brain systems that are derailed by addiction.

“We’re learning that exercise is a type of medicine that has broad effects on the brain,” says Wendy Lynch, associate professor of psychiatry and neurobehavioural sciences at the University of Virginia. “Initially, when somebody starts using a drug, it’s pretty much about dopamine and that is linked to euphoria. But, after a while, you get less and less of a dopamine response. Drug addiction becomes more about the need to relieve the negative symptoms – the craving, the withdrawal symptoms.”

Lynch started looking at how exercise can normalise systems that have been thrown out of balance and ease those cravings. “So far,” she says, “the evidence suggests all types of exercise – even in small amounts – lead to beneficial effects. From my research, it’s more about the timing of exercise than how rigorous it is, or how long it occurs for.”

Even modest exercise for someone still in the withdrawal phase will, she says, “relieve withdrawal symptoms and prevent some of the brain changes that underlie cravings”. While it may not seem a great idea for very ill people to exert themselves, if a brisk walk is possible, they will reap benefits.

In 2014, Dan Blomfield entered rehab in Cornwall. He had always been a work-hard, play-hard type, but the balance eventually tipped the wrong way. “I’m a teacher, and I was working in front of a class of teenagers with a Lucozade bottle with vodka in it on my desk. I was drinking two litres of vodka a day,” he says. While hospitalised for a third time with alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis, he emailed Addaction Chy, a residential rehabilitation centre run by the drug, alcohol and mental health charity Addaction.

A month or so into the programme, on Christmas Day, he went for a run, something he had never enjoyed before, being more the snowboarding and wakeboarding type. “I wanted to do something celebratory,” he says, “and I got an instant feeling of connection in my body. My mind was getting clearer and I felt connected to nature.”

From then on, he ran for at least 20 minutes most days; in the past year, he has completed two marathons. At first, however, he ran alone, and he believes there is “a massive hole in the market” for running and sports groups for people with addictions. “In rehab, one of the facilitators would voluntarily run an exercise course on a Friday, and we were told in various meetings that we had to exercise, and we did have a heavily reduced membership to a gym in town, which we were encouraged to join. But a club for people in recovery wasn’t on offer.”

Back in the US, Mitchell says that as well as the physiological gains, the Skid Row running club provides “the benefits of getting to know people in a setting that allows you to have very meaningful interactions. If you run 10 or 15 miles with somebody, at some point along that course the conversation is likely to turn serious.”

At a time when someone might feel unworthy of friendship, this social element is valuable. Even addicted hamsters starved of company will chose social interaction over drugs. Lynch mentions a study in which the rodents could press a lever to get drugs or another that would bring a second hamster into their cage. “Regardless of their drug exposure, how long they’ve been using it, how addicted they are, even the severely addicted animals by all these different measures will chose the social peer.”

John Milligan is a senior addiction worker for the South Glasgow Community Addiction Team and has led the club Recovery Runners on a voluntary basis since 2014. His members do two weekly evening runs, along with a longer outing on Saturdays for about 30 of the more experienced runners. The club’s WhatsApp group is bubbling with “banter, kidding and joking”. Many of the Recovery Runners, he says, “have never had that closeness where you can have that laughing and joking”. And even when people really don’t feel like running: “When they get going they talk about what’s been bothering them and they get peer support.”

The Recovery Runners also organise 3k, 5k and 10k races, which anyone can join free, and if the people with addictions he works with don’t want to run, or aren’t able to, they can help to manage the events instead. “There are medals, marshals, official times along with registration,” says Milligan, and by helping with these, “they are inspired by being useful – but also, because they cheer people on, they get something back from the runners.”

Another big issue that Milligan sees is concern over physical appearance. When addicts are using, he says: “They’re almost like a pack of wolves, constantly on the go, foraging for more money to get more drugs. So, when they stop being chaotic they tend to start eating better, moving less and piling on weight. One of the side-effects of turning your life around is that you put on a stone or two.” This perceived fatness can lead to relapse, so running is a way to keep the weight down and improve body image. “A lot are smokers, too,” Milligan adds, “and the ones that persevere with running usually stop smoking or cut down.”

While he says the initiative is effective enough, there is more that could be done. But in the current financial climate: “There isn’t that level of funding to dedicate a salary to encouraging people to run.”

Mitchell sees his work on Skid Row as “a micro-solution to homelessness and addiction. It’s very much a one-on-one, intensive enterprise. Policymakers need to create opportunities and mechanisms where one human being can have a meaningful, supportive and nurturing relationship with another.”

His hope is that the film will show people how: “For ordinary folks like myself, being able to get up early, go out and run and talk and maybe have a little breakfast afterwards, that’s where the human investment begins to pay dividends.” People elsewhere in the US have told him they are starting similar clubs.

Mitchell says he gets as much out of running on Skid Row as the other members. “Not only do I care deeply about the other runners but I know they care deeply about me. And when the runners who make good choices get off the streets, it’s incredibly rewarding for me.”

It benefits wider society, too. “You look at someone like Rebecca, a heroin addict.” he says. “She is now a surgical technician working in a hospital setting. Every patient she deals with is reaping the benefit of her having been able to reclaim her life. Ben Shirley, who was in the gutter, what is he doing now? He’s composing full symphonies for us. I have understood by involving myself in this programme the untapped human potential that is out there in some of the most unlikely places.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion