Editor’s Note: Ghaffar Hussain is managing director of Quilliam, a think tank formed to combat extremism in society. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely his.

Story highlights

We must examine why ISIS narrative has resonance and appeal, writes Ghaffar Hussain

Hussain: Groups like ISIS restore collective pride to Muslims feeling victimized, humiliated

Blame can be shifted to perceived enemy and sinister anti-Muslim conspiracy theories, he adds

Mainstream Muslim commentators must promote positive role models, Hussain says

In recent months, much ink has been spilt exploring why some young British Muslims abandon a comfortable life in the UK to join one of the most brutal and blood-thirsty terrorist groups in recent history, namely the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Sadly, much of this commentary has struggled to move beyond clichés that revolve around hate preachers and extremist websites.

In order to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of why a group like ISIS is able to attract hundreds of young British Muslims, we must examine a wide range of factors that contribute towards creating a ISIS narrative that has resonance and appeal.

This involves facing up to some uncomfortable truths about contemporary Muslim political discourse and coming to terms with the negative impact of the recent lurch towards vacuous literalism within British Muslim communities.

There is a fundamental cognitive dissonance in the minds of many young Muslims in Britain today. On one hand a conservative religious upbringing informs individuals that they alone have the true holy book, the true God and, of course, the true religion. This gives rise to lofty expectations for Muslim societies globally. However, the reality of contemporary Muslim societies, mired in poverty, illiteracy, violence and corruption as they are, stands in stark contrast to such grand expectations.

This perturbing juxtaposition requires an explanation that neither denies the perceived reality nor challenges Muslim exclusivist tendencies. Such an explanation or narrative needs to take into account the sense of victimhood and humiliation some Muslims feel and seek to externalize. It also needs to offer a program for restoring much-needed collective pride.

In essence, groups like ISIS are filling this gaping void, a void other post-colonial nationalist movements have failed to fill. In the eyes of the jihadists, Muslim societies around the world are struggling today because they have been systemically undermined by western neo-colonialism and strayed from the true Islam. The solution, therefore, is to expel any semblance of western influence, along with their local stooges and puppets, and introduce a strict and harsh interpretation of Islam.

The attraction for some is then obvious since by this narrative a struggle to understand complex geo-politics is replaced with a simplistic “one size fits all” framework. It does not require one to expend energy in difficult and searching introspection since all blame can be shifted to the perceived enemy and sinister anti-Muslim conspiracy theories.

It replaces the quest for a firm sense of identity in an increasingly globalized and, at times, disorientating world with a militant and aggressive Muslim identity that seeks conflict rather than co-existence in order to distinguish itself, be relevant and create tribal cohesion.

Some Muslims who don’t subscribe to the tactics and ideological world-view of groups like ISIS still buy into the broad narrative such jihadist and Islamist groups purvey. The adoption of this broader narrative has become the default anti-establishment politics of today. It is a means of expressing solidarity and asserting a bold new identity while being a vehicle for seeking the restoration of pride and self-dignity.

Of course, for most British Muslims the ISIS narrative has no resonance whatsoever and alternative narratives to ease the cognitive dissonance are sought. However, the steady increase in ultra-conservative Islamic mores in recent years, backed by petro-dollars from Gulf Arab States, has meant the number of young Muslims that do sympathize with the ISIS narrative is alarmingly high. After all, the ISIS reading of scripture deviates very little from the Wahabism aggressively promoted by certain Gulf States.

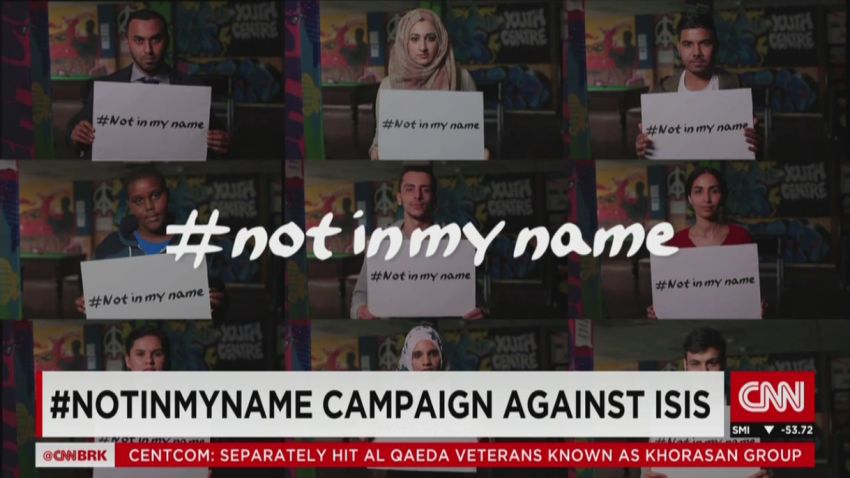

The hundreds of British nationals did not abandon their families in the UK to join ISIS in a vacuum. The proliferation of literalist and austere strands of Islam combined with the inability of mainstream Muslim commentators to articulate a political narrative that does not reinforce the victimhood status and perceptions of grand anti-Muslim conspiracies have paved the way for ISIS propagandists. In the meantime, the over-reliance of Western states on law and war as a means of combating what is ultimately an ideological threat has meant extremist recruiters have yet to encounter a direct ideological challenge.

As things stand, British and other Western-born Muslims will continue being recruited to groups like ISIS as long as we fail to diagnose the problem correctly. A correct diagnosis needs to be followed by a direct and robust ideological challenge that is accompanied by alternative models and narratives for explaining the decrepit state of Muslim societies. Of course, positive political models that young Muslims can aspire to also need to be articulated in a fashion that does not alienate or patronize.

In the absence of this, dark forces that rely on unprecedented levels of brutality will continue to rise and fill a void we failed to identify.