The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which now controls a vast swath of both countries and is at war with nearly every government in the region as well as the United States, did not come from nowhere. Its rise is rooted in history, in the wars that have torn apart governments and societies in the region, and in a series of disastrous choices made by the very forces now fighting ISIS. These maps tell that story and hint at what may come next for a group that President Obama called a "network of death."

-

Religion and ethnicity in the Levant

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria is a result and a driver of sectarianism, not of diversity itself, but to understand how the group works and where it comes from you still have to understand the religious and ethnic composition of the region. You can immediately see two key facts on this map. First, big parts of Syria and Iraq are ethnically Arab and religiously Sunni Muslim, marked in yellow; so is ISIS, and they principally operate in those yellow areas. Second, much of the region is quite diverse: a big chunk of southern Iraq is Shia Muslim and Arab. And there is an ethnically Kurdish minority stretching across both countries, while western Syria is a super-diverse mix of Shia, Christian, Druze, and other groups. Those non-Sunni, non-Arab groups are running the governments of both countries, which is a source of real unhappiness among Sunni Arabs who feel dispossessed. But now ISIS is also brutally oppressing, and in many cases massacring, all other sectarian groups. The fact that national borders don't line up with ethnic and religious lines did not cause ISIS or the larger conflicts, but it has become a major part of the violence.

-

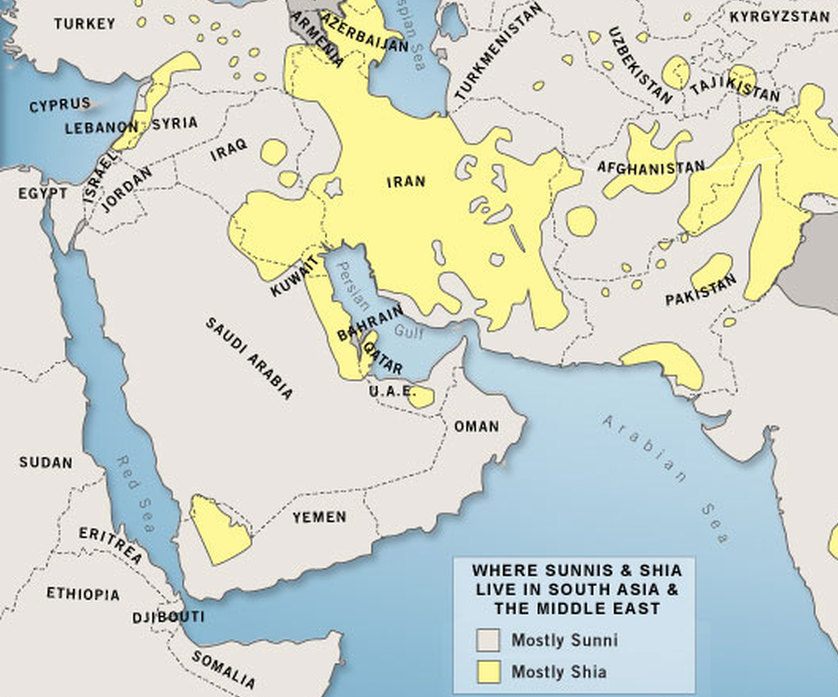

The Sunni-Shia divide

Now let's zoom out and look at just the concentrations of Sunni and Shia Muslims across the Middle East. Sunnis and Shias have not, despite what some people say, been at conflict with one another for centuries; this sense of sectarian hatred is recent. But it does matter a great deal today, particularly for ISIS, and that has to do with where Shias, the smaller of the two sects, are concentrated. They have a large enough majority in Iraq to rule, and the post-Saddam Shia government has not respected Sunnis. In Syria, meanwhile, the Shia minority in power has long abused the Sunni majority. So there is a sense of Sunni dispossession in both countries. Meanwhile, the governments in the region have divided between Shia governments and Sunni governments, driven in part by Sunni-led Saudi Arabia and Shia-led Iran, which see themselves as being in a regional struggle for hegemony that has fallen along sectarian lines. That has played out especially in Syria, with Iran backing the government and Saudi Arabia backing the rebels, which eventually gave rise to ISIS.

-

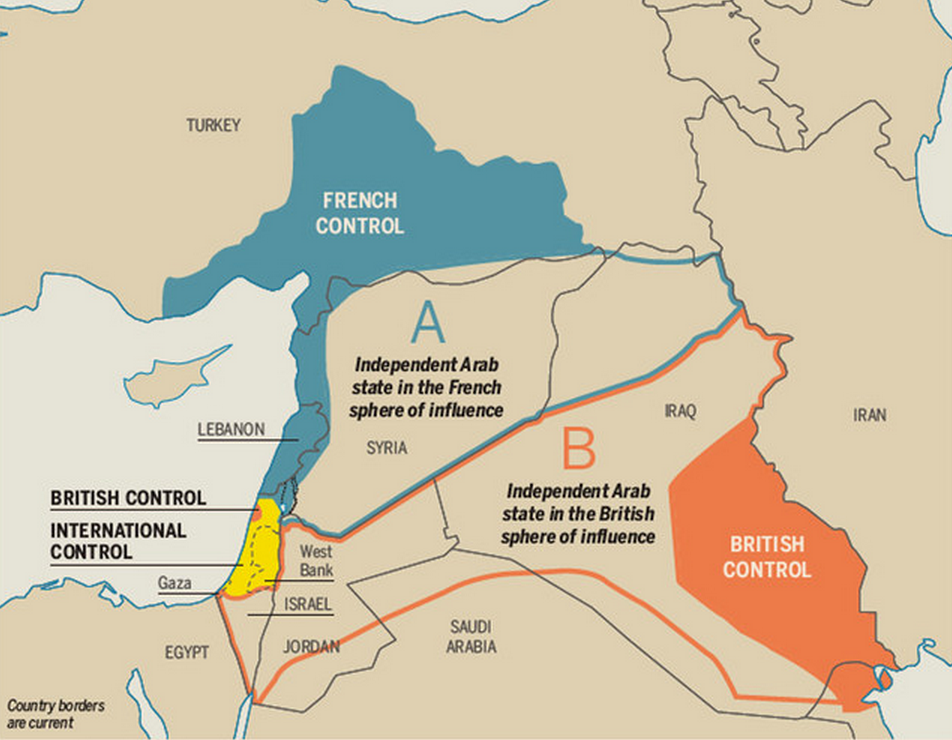

The Sykes-Picot agreement that set Iraq and Syria's borders

You hear a lot today about this 1916 treaty, in which the UK and French (and Russian) Empires secretly agreed to divide up the Ottoman Empire's last Middle Eastern regions among themselves. Crucially, the borders between the French and British "zones" later became the borders between Iraq, Syria, and Jordan. Because those states had largely arbitrary borders that forced disparate ethnic and religious groups together, and because those groups are today in conflict with one another, Sykes-Picot is often cited as a cause of warfare and violence and extremism in the Middle East. Scholars are still debating this theory, which may be too simple to be true. But the point is that the vast Arab Sunni community across the Middle East's center was divided in half by the European-imposed Syria-Iraq border, then lumped in to artificial states with large Shia communities. Compounding the problem, the Europeans often promoted a minority leader, who would then be reliant on outside support, which created legacies of unstable minority rule.

-

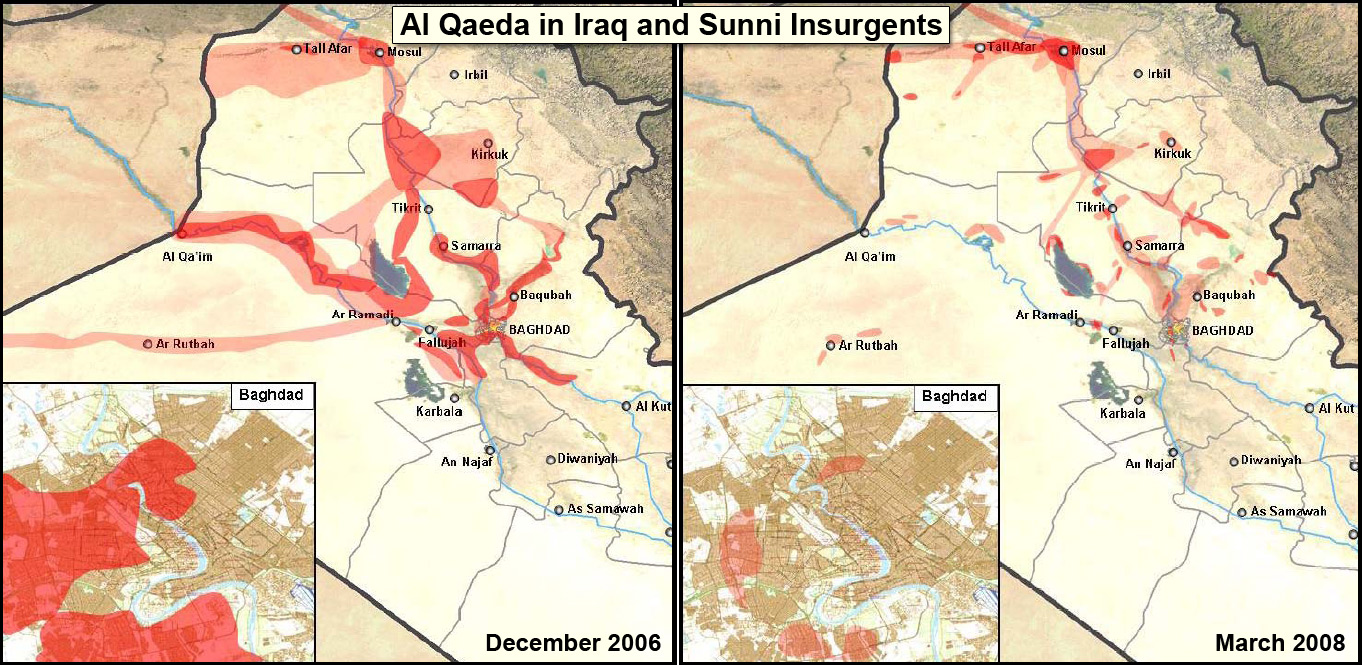

Al-Qaeda in Iraq's rise in 2006 and decline in 2008

ISIS was formerly known as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), a name that originates with its 2004 pledge of allegiance to al-Qaeda. At its peak in 2006, AQI controlled significant chunks of Sunni Iraq, and even set up a quasi-government in some of the land it controlled. However, Iraq's Sunni population turned on AQI — partly out of anger with its brutal rule and partly out of political interest. This Anbar Awakening, named after the province in which it began, resulted in former Sunni insurgents and tribal militias partnering with American and Iraqi militaries. AQI was roundly defeated: it lost effective control over almost all of its previous domain and nearly 95 percent of its personnel. The fall of AQI illustrates just how much ISIS depends on support from Sunnis in Iraq. If it angers the population, they can provide critical intelligence and cooperation that would allow the Iraqi military to crush them, or tribal militias could fight ISIS outright again. That's why Iraq's new Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi, is so critical: his heavily Shia government could attempt to address Maliki-era Sunni grievances. Or it could double down on sectarian policies, as some of Abadi's coalition partners want, thus handing a major weapon to ISIS in the war over Sunni public opinion.

-

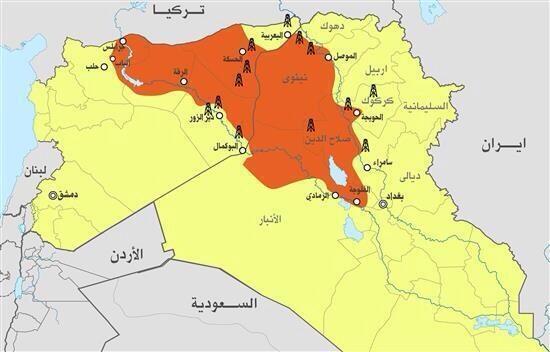

ISIS's 2006 plan for Iraq and Syria

This map is hypothetical, but the fact that it exists at all speaks to the ambition of ISIS. Aaron Zelin, an analyst at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, found this 2006 map produced by ISIS, showing the areas it hoped to control and overlapping oil sources. The correctness of the map aside, it shows that the group has been thinking about the economics of its war and how to self-fund. It currently controls much of this desired territory, and some reports indicate ISIS has some oil production and refinery facilities, a big step toward being able to fund its own war.

-

The Arab Spring

The Arab Spring protests seemed, early on, to promise a new, more hopeful Middle East. After the fall of the Tunisian, Egyptian, and Libyan dictators, it looked like Syria's Bashar al-Assad was next. Once the Syrian protesters armed in response to Assad's crackdowns, he waged an intentionally sectarian war, designed to pit Shiites and other religious minorities against Syria's majority-Sunni population. This allowed ISIS, a radical Sunni group, to move into Syria and flourish. Meanwhile, Iraq experienced its own version of the Arab Spring in late 2012, when Sunnis took to the streets to demonstrate against perceived slights by the majority Shia government. The failure of the Sunni protest movement, as well as harsh government repression, caused many Sunnis to turn to insurgency. The failure of legitimate protest to resolve political problems in both Iraq and Syria sparked the violence in which ISIS flourishes.

-

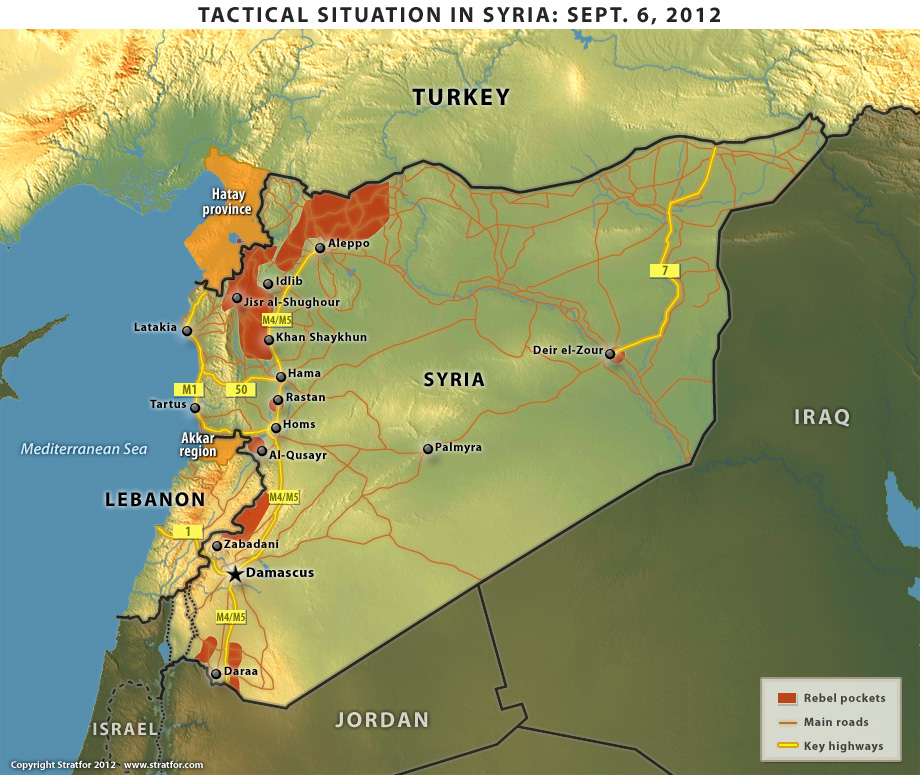

The Syrian civil war, late 2012

This shows the war in its more optimistic early stages, when it was mostly fought between the Syrian government and a homegrown uprising of Syrian rebels who wanted to topple it. ISIS and other extremist groups, composed heavily of foreign fighters, had not yet emerged as major forces. You can see the initial uprising was mostly in the West, where the big population centers are, especially in areas just outside of major cities like Daraa and Aleppo. This is important because these rebels are still in a lot of these areas, while ISIS is concentrated in the east and the north, and the two groups are in competition — and sometimes at war. It's also important to see just how much the lines of battle have changed since 2012, and to get a reminder that ISIS began as an invading army in Syria from Iraq.

-

Iraq's 2012-2013 Sunni protest movement

Former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki did a lot to assist in ISIS's rise. Since becoming Prime Minister in 2006, he centralized a great deal of power in his office, and ran the Iraqi government along Shia sectarian lines. Naturally, this infuriated Sunnis, who organized a series of protests around the country in 2012. These continued into 2013, and the Maliki government began to see them as a serious problem. Unable or unwilling to resolve the protests politically, Maliki turned to force. His security services killed 56 people alone at a protest in the northern town of Hawija in April 2013. The forcible breakup of the protest movement convinced some Sunnis that their only solution was military, helping militant groups like ISIS and the more secular Jaysh Rijal al-Tariqa al-Naqshbandia (JRTN) recruit from and curry favor with the Sunni minority.

-

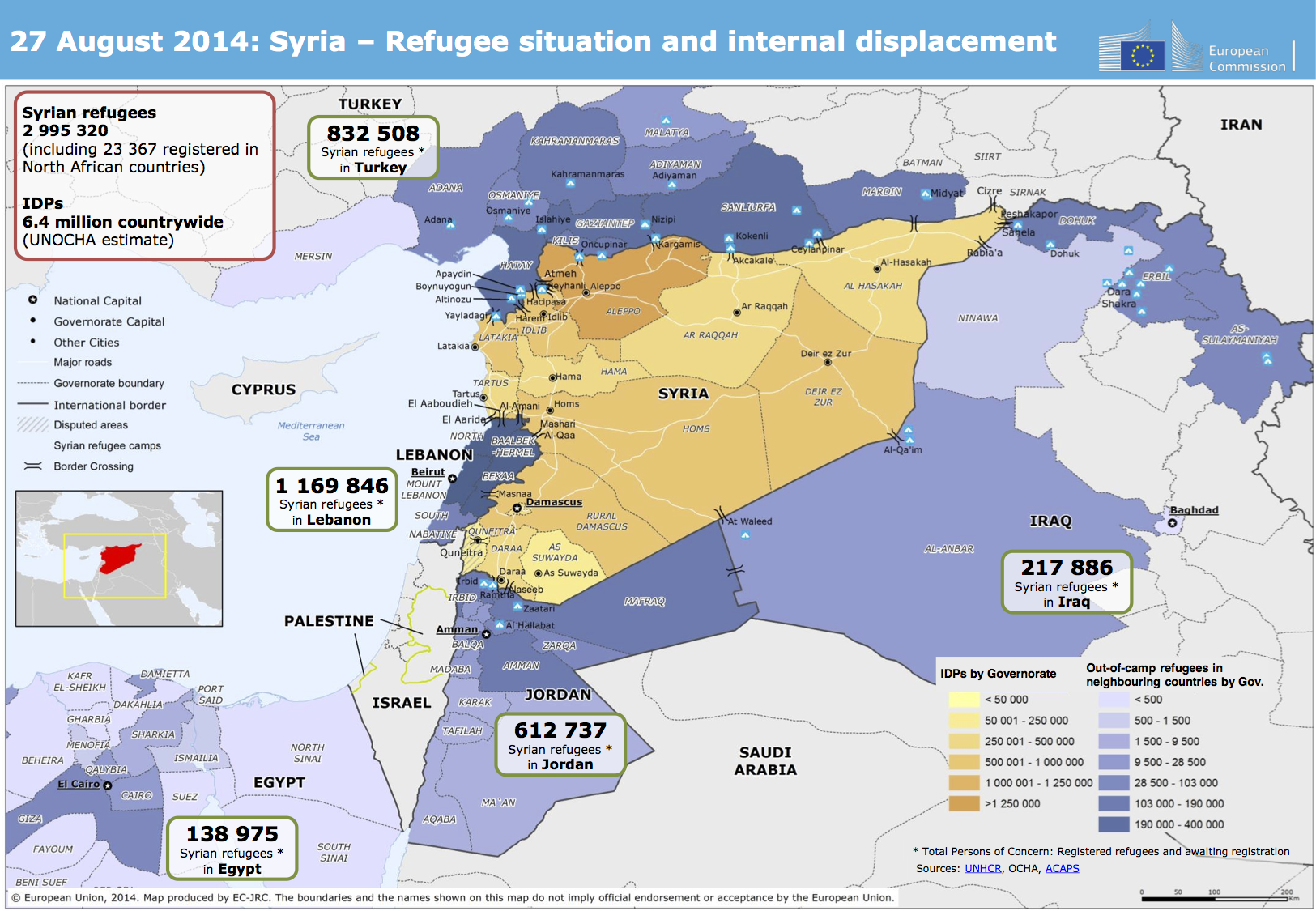

Refugees and internally displaced Syrians

The Syrian civil war, in only three years, has destroyed Syrian society down to its very roots, a fact that is illustrated by this map of its three million refugees and six million internally displaced persons (IDPs). To put these numbers in context, Syria's entire population is only 23 million. The chaos has opened a vacuum that ISIS can fill. Syrians inside the country who would otherwise abhor ISIS and its brutality might be willing to accept just about any group that can provide some measure of stability, which ISIS reportedly has in some places. And the flows of refugees out of Syria are accompanied by flows of foreign fighters and foreign arms in. Even if ISIS disappeared tomorrow, the IDP and refugee crisis would remain, bringing not just suffering but instability and unrest for at least a generation.

-

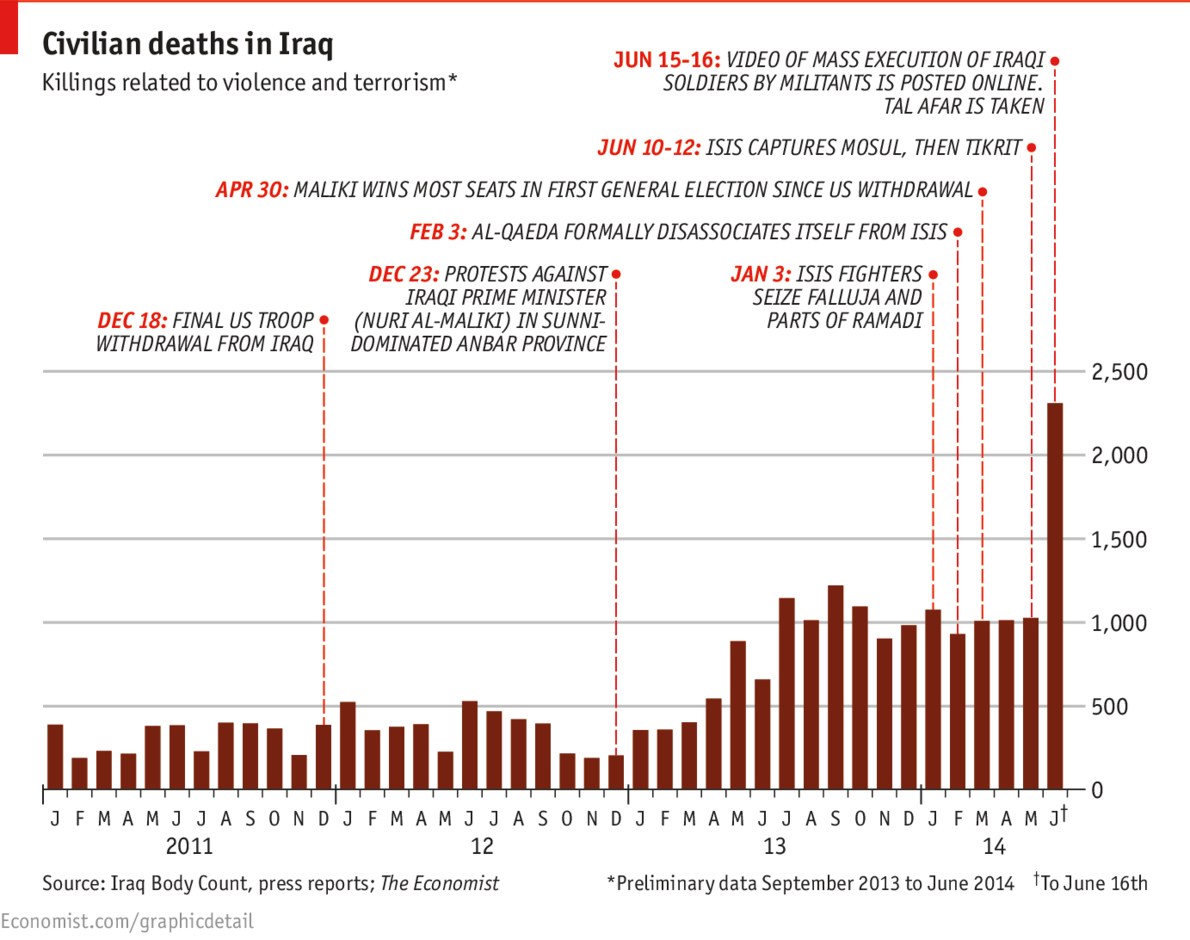

Casualties in Iraq from 2011-June 2014

This chart of civilian deaths shows just how violent the ISIS uprising has been. Until about May of 2013, civilian deaths from violence were pretty stable. Then, after the government crackdown on protesters in Hawija, near Kirkuk, violence began increasing as ISIS launched more lethal terrorist attacks, and support for a Sunni anti-government insurgency grew. The next big spike in civilian deaths is June 2014 — when ISIS launched the offensive that conquered Mosul, Iraq's second largest city, and major chunks of northern and western Iraq. Since June, casualties in Iraq have remained relatively stable at this high point, which rivals the post-American invasion insurgency in intensity. That's how serious the current, ISIS-driven crisis is.

-

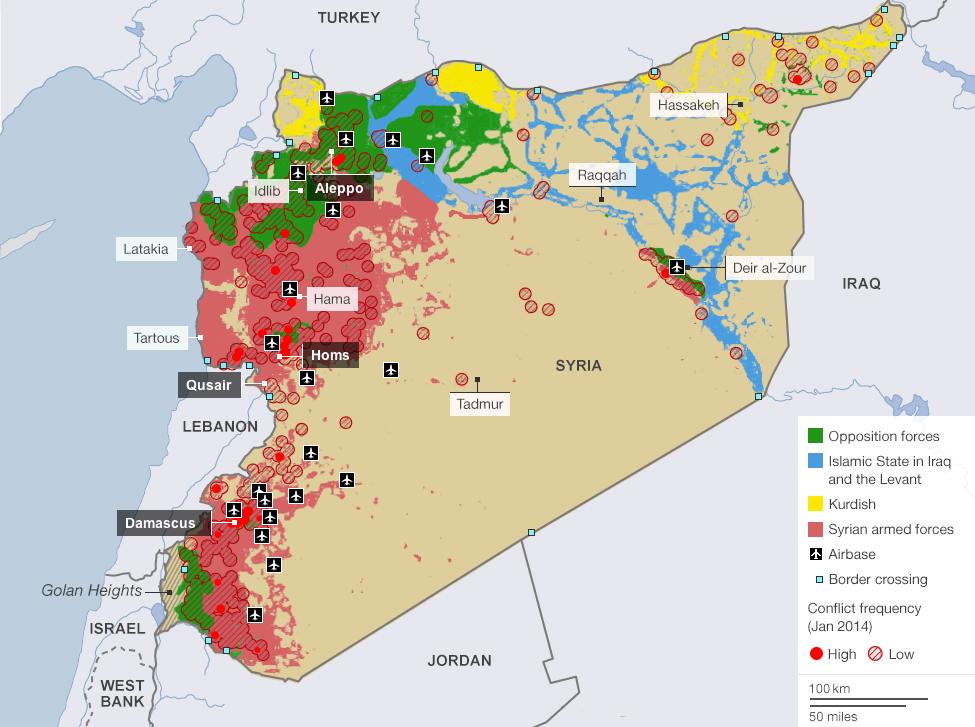

Syria's four-way civil war, March 2014

By early 2014, Syria's war had changed into something very different, with regime forces (in red) fighting against the preexisting rebellion (green) as well as the new and more capable force of ISIS fighters (blue), who are also fighting against the Syrian rebels and the Kurdish militias (yellow). This has happened in part because extremists have received funding from Gulf countries, in part because they are better at attracting foreign fighters, and in part because Syria's government has refused to target ISIS, correctly believing that foreign powers like the US may hate Assad but would ultimately prefer him to ISIS. All of that helped give ISIS a staging ground, territory, and battlefield training for its rise and expansion.

-

ISIS territory in Syria and Iraq, Sept. 2014

With its base secure in eastern Syria, this summer ISIS launched a massive invasion of Iraq's Sunni regions, its original home as AQI. It now controls a vast stretch of territory the size of Belgium, from the edges of Syria's dense western cities all the way to the outskirts of Baghdad, creating an unofficially autonomous Sunni zone that has effectively erased the Syria-Iraq border. The group's headquarters are in Raqqa, a Syrian city, but it also controls Mosul, one of Iraq's largest cities, and many others. To control and govern these cities is an astounding feat, one that provides ISIS with a revenue base and plenty of operational centers, but it's also a weakness as it leaves ISIS reliant on the acquiescence of this population. Should Sunnis in these cities rise up en masse, as the US is hoping they will, it could drive back the group.

-

Energy resources in ISIS territory

Syria is not a super-oil-rich country, and most of Iraq's oil is in the south beyond ISIS's reach. But the group still controls an awful lot of land with not just oil but important oil infrastructure, especially pipelines and refineries. This has plugged ISIS directly into the global energy market, allowing them to develop a mini oil economy, with which they can fund their rampage as well as buy off locals who felt that the Iraqi and Syrian governments were depriving them of their fair share. The US and others are bombing this infrastructure, hoping to stem ISIS's income, but the fact that there is even any oil income to cut off is astounding and, in itself, a sign of ISIS' scope.

-

US air stikes against ISIS

These are the early US air strikes against ISIS in Iraq, which began in August, and then in Syria in September. They're meant to accomplish three things: to drive ISIS back from Baghdad, from important Iraqi dams, and other places the group has not yet taken; to destroy some of the energy infrastructure funding the group; and to destroy some of its infrastructure and heavy weapons in major cities like Raqqa. But these strikes alone will not defeat ISIS, and everyone knows it. The group rose to power before it had any of that infrastructure in the first place. Defeating the group will require a ground invasion force of some kind to re-occupy all that territory, and it will require Sunnis in Syria and Iraq to shift their support from ISIS to whoever replaces them. In Iraq, the hope is that the country's new prime minister will reach out to Sunnis and build up the Iraqi military enough to re-take the territory. In Syria, there is simply no good and viable option, which means there is as yet no foreseeable way to end this.

Credits

- Developer Yuri Victor

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/40007952/453396050.0.0.jpg)

/cdn1.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/1396420/isis_control_0922.0.png)