Up against bad PR and a lack of awareness, reproductive health groups are leading the charge to make the IUD a first line of defense against unplanned pregnancy. It won’t be easy.

Most women have been there: sitting in their gynecologist’s office, having yet another unsatisfying conversation about yet another unsatisfying form of birth control, wanting to try something new.

Take Marlice House. By the time she was 17, she’d already cycled, as many women do, through various versions of the Pill, but the hormones gave her headaches, or caused her to gain weight, or she would forget to take her pill and be plagued with anxiety. She switched to the NuvaRing, a flexible loop that’s inserted in the vagina, where it emits hormones that prevent fertilization, but she hated the way it felt inside her.

House’s gynecologist referred her to the CHOICE Project at Washington University Medical School in St. Louis. CHOICE is an ongoing study of 10,000 women’s contraceptive use that also offers family-planning counseling. There, for the first time, House was told about the intrauterine device (IUD). Among its selling points were the fact that the IUD is hassle-free, lasting three to 12 years without maintenance or replacement, depending on the brand. It’s also practically fool-proof, on par with female sterilization or vasectomy at preventing pregnancy.

“I thought, ‘That’s it,’” says House, who is now 25 and a social worker in Missouri. She was sold.

Yet American women—and the doctors who counsel them on family planning—have been slow to adopt it. Today, just 9% of American women of child-bearing age use an IUD, the lowest rate of any developed country. And more than half of U.S. women surveyed have never even heard of the thing.

But there’s a growing push for women to consider one. Because as successful as health groups have been at reducing accidental pregnancies, particularly among teenagers, half of U.S. pregnancies are still unplanned.

“If you can eliminate a lot of them by taking out the human ability to screw up, you’ve done fabulous stuff,” says Dr. Mary Jane Minkin, a clinical professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive services at Yale School of Medicine.

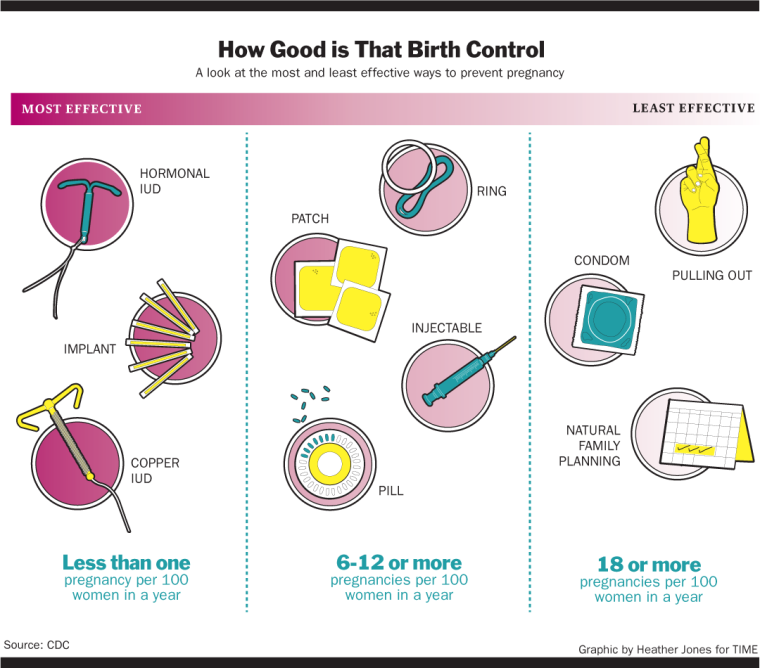

Some early signs are promising. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that many women try at least five different kinds of birth control and are unhappy with all of them—suggesting it may be a ripe time for alternatives. Meanwhile, Planned Parenthood reports a 75% increase in IUD use among its patients since 2008. But the dual challenges of terrible PR and a lack of awareness among the doctors who issue family-planning advice means that the shift away from the pill-a-day or condom approaches—and toward long-term contraception—won’t be easy.

The IUD is a very small T-shaped rod inserted by a doctor into the uterus, where it emits either the hormone progestin or copper, both of which are hostile to sperm. There are three FDA-approved IUDs available in the U.S.—Mirena and Skyla, which are hormonal, and ParaGard, which is wrapped in copper coils—and they are all extremely effective, with a failure rate of less than one pregnancy per 100 women—compared with 9 per 100 women on the Pill.

“Leading medical organizations now recommend them as a first-line choice,” says Megan Kavanaugh, a senior research associate at Guttmacher Institute, the reproductive rights nonprofit, who points out that while IUDs were historically recommended for women who had already had a first child, that’s no longer the case. In 2012, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, considered the authority on reproductive health, hammered home that message, concluding that IUDs are safe and appropriate for adolescents.

So why the slow rate of adoption in the U.S.? It’s largely due to the fact that the IUD is still the subject of widespread misconceptions. The device is plagued by a troubled history dating back to the ’70s, when an earlier version of the device called the Dalkon Shield was yanked from the market after being linked to infertility and infections. Current versions are smaller and far safer, with almost none of the risks, but the stigma is hard to erase—both among women and also among the physicians who prescribe birth control.

Until recently, the IUD could also be expensive—up to $900 upfront for the uninsured. But a provision in the Affordable Care Act requires coverage for all FDA-approved contraceptives, with the exception of women whose health plans are sponsored by religious employers. (The Supreme Court recently ruled that for-profit corporations whose owners say they run their business on religious principles do not need to cover emergency contraceptives. The IUD can act as emergency contraception if inserted after unprotected sex since it prevents fertilized-egg implantation in the uterus).

Another obstacle is a lack of awareness. The IUD is still virtually unknown to more than half of American women, according to numbers crunched by the Guttmacher Institute. Yet according to the CHOICE Project’s early findings, once women learn about the IUD, more than half will opt for it.

“We thought cost and accessibility were the only barrier,” says Gina Secura, an epidemiologist and CHOICE’s project director, who formerly worked at the CDC. “But when we asked the first participant, ‘What method would you like?’ she asked, ‘What are my options? The Pill?’ We realized we had a lot of educating to do.”

Trepidation about the IUDs of yesteryear is not unwarranted. IUDs started emerging on the U.S. market in the 1950s, and by the early ’70s, one particular brand, the Dalkon Shield, hit sales of 2.8 million, according to the CDC.

But the Dalkon had flaws. Unlike T-shaped IUDs, the Dalkon was shaped more like an insect with several legs sticking out on either side of it. That made it difficult to insert, resulting in it being placed incorrectly, and also resulting in IUD failure and pregnancy. Doctors and manufacturers also didn’t know that the IUD needed to be taken out if a woman got pregnant—but if it wasn’t, it could lead to serious infections. According to various reports, upwards of 15 women who became pregnant with a Dalkon IUD inside them died of infections after they miscarried.

The Dalkon Shield was besieged with lawsuits, and in 1974, the manufacturer, A.H. Robins Co., voluntarily pulled the product from the market. A few years later, A.H. Robins filed for bankruptcy, and by 1986, virtually all brands of IUDs had disappeared from U.S. shelves.

The Dalkon Shield was also linked to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), a painful condition in which the lining of the uterus, fallopian tubes, or ovaries can become inflamed and can lead to infertility.

But Yale’s Minkin, who was called in as a medical expert in one of the suits against the Dalkon Shield, says the downfall of the IUD was much more complicated than a single product. Minkin says that many cases of PID might have been due to STDs like gonorrhea and chlamydia during the ’60s and ’70s. “So you have a sexual revolution, burgeoning chlamydia, women not using condoms or birth control pills, and bingo! You have a problem,” says Minkin. “It was terrible because women lost a good method. People got hysterical.”

After the Dalkon Shield, “concerns were the same around the world, but no one had the same reaction as the U.S., where IUDs virtually disappeared,” says Dr. Carolyn Westhoff, the senior medical advisor for Planned Parenthood Federation of America. By the late 1980s, there was interest among some health groups to bring back the IUD, particularly outside the U.S. “The Mirena IUD got pioneered in Europe in the early ’90s and caught on like wildfire,” says Minkin. Today, 23% of French women using contraception have an IUD; 27% of Norwegians; and 41% of women in China. In the U.S., the percentage of women with an IUD still hovers around 9.

The IUDs on the U.S. market today are much safer than the IUDs of earlier generations, but not everyone is convinced. “These misperceptions are leftovers from 30 years ago,” says Dr. Laura MacIsaac, director of the family planning division at Mount Sinai Health System in New York. “They have no relevance to the devices of today. These myths persist mostly from physicians’ fears that today’s IUDs still have the same flaws as the old ones. That’s just not true.”

That’s not to say modern IUDs are without side effects, though for the overwhelming majority of women, they are mild. The copper IUD, for instance, can cause heavy periods and cramping in some women for the first few cycles after insertion. Some women with hormonal IUDs report cramping and abnormal bleeding. And in extremely rare cases, the IUD can migrate from the uterus or puncture the uterine wall—which is the subject of several lawsuits against Mirena. Mirena manufacturer Bayer says the company “has adequately disclosed all known risks associated with Mirena since the FDA first approved it in 2000.”

When asked about the risks, MacIsaac says: “Our data shows IUD users have the fewest amount of problems and complications and the highest continuation rate of any other category of birth control. … The women who are happy with their IUDs and have no problems are not the ones who get in the press.”

Reproductive health experts believe the time is right to re-educate doctors—and women—about the new generation of IUDs. According to the CDC, 30% of women will try at least five different kinds of birth control, and for women not happy with the Pill, who want a non-hormonal contraceptive, or who are concerned about its side effects, the IUD is an effective way to avoid pregnancy.

Launched in 2013, New York City’s IUD Taskforce is one of the first initiatives of its kind. It’s made up of about 50 people from major reproductive health organizations like the Guttmacher Institute, the nonprofit Public Health Solutions, and the New York City Department of Health. The taskforce trains physicians how to insert them, provides women with facts about IUDs, as well as information about where women can get them.

“IUDs help women work on other parts of their life before they’re ready to have kids,” says Louise Cohen, vice president of Public Health Solutions. “We want to increase the degree to which women learn about them—whether through a physician or social media—and we will have them readily available when they want them.”

Another initiative is the New York City Department of Health’s new smartphone app “Teens in NYC Protection,” which uses GPS to show teens where they can get IUDs and other forms of contraception, like condoms. “When we make teens aware, it creates a network, and that’s very powerful,” says Deborah Kaplan, assistant commissioner of the New York City health department.

One of the more viral campaigns comes from the irreverent website Bedsider.org. Bedsider is an online birth control support network operated by the not-for-profit National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. The campaign has an edgy social media presence on Twitter and Instagram with the hopes that tongue-in-cheek messaging will appeal to young adults.

The IUD is also gaining popularity among the group it was originally targeting: moms. When the Mirena, one of the two hormonal IUDs, was first introduced in the U.S. in 2000, moms were their main target group. “The thought was that moms were so busy, and when they finally found a few minutes of free time to have sex, the last thing they had to worry about was contraception,” says Minkin.

Among younger women, word of mouth is key to growing awareness, say experts. House, who wasn’t born when the original IUDs were pulled from the market, says none of her friends knew about IUDs before she got hers inserted at 17. “Now I’ve recommended it to so many of them. I think about three of them actually got it,” she says.

Even though data shows American women’s use of IUDs is the lowest in the developed world, the small but significant growth herald a sea of change. “I recommend the IUD for pretty much anyone walking into my practice wanting contraception,” says Sinai’s MacIsaac. “Most of us who have a lot of clinical experience with the IUD are hoping use in the U.S. will start to look like use in Europe. My goal is to help women plan their families, education and professional life. And IUDs help them do just that.”

Updated: June 30, 10:55 a.m.