In a way, ecosystems are like markets—ones with perfect competition, where the struggle to eat and avoid being eaten long enough to breed is so intense that no market participant can dominate. Evolution, in other words, makes ”disruptive innovation” impossible.

Until the rise of global trade, that is. Transporting a given species to an alien ecosystem that had never adapted to its traits is similar to what tech writers might call ”creating new markets,” by changing how technology—i.e. those traits—could be applied.

Sometimes this disruption has been so stark that it created a monopoly—placing a species in an ecosystem with plentiful food and no natural predators. Without any competitive threats, the species takes over.

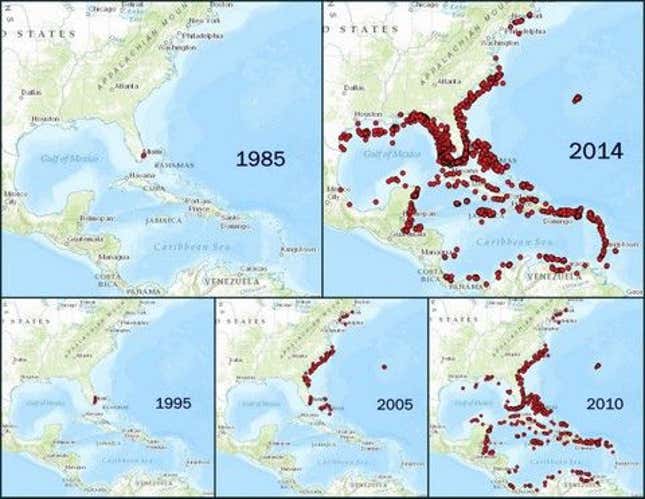

If that sounds a touch apocalyptic, consider the lionfish. Native to Indo-Pacific coral reefs, these venomous creatures have long been admired by aquarium fanatics for their toffee coloring and frilly halo of fins and quills. The global explosion of the aquarium made them common in living room seascapes everywhere. Then in 1985, someone released 10 or so female lionfish in south Florida waters. DNA analysis traces the entire Atlantic population back to those females.

And it’s an extensive lineage. In less than three decades, lionfish have colonized a swath of the Atlantic Ocean that’s roughly the size of the US.

How have they spread so far, so fast? Their focused savagery explains a lot. Recent research shows that instead of moving on to more fish-abundant waters, they will continue to hunt target prey until they’ve eaten every last one of them, pushing the species to local extinction.

They’re also gluttonous. Upon opening some specimens up, marine biologists off the coast of North Carolina were shocked to find something they’d never seen before: waxy lumps of fat. Lionfish are getting not just overweight but downright obese—gorging themselves so violently they were destroying their own livers.

Fish don’t get fat in their natural habitat. For one thing, surviving involves a lot more cardio exercise, since their prey know to avoid them. And while chasing down dinner, lionfish also have to dodge their own natural predators, mainly groupers and moray eels (oh—and themselves; when food is scare they’ll eat their young).

But the Atlantic Ocean’s “market participants” have never before faced this disruptive new competitor. The lionfish’s new prey aren’t evolutionarily primed to flee from them, and no bigger predators have adapted a taste for them, says Carl Safina, founder of the Blue Ocean Institute.

This is why, in five weeks, a single lionfish can wipe out four-fifths of a reef’s small fish. Worse, they’re also prolific breeders; they hit sexual maturity within a year and start cranking out 40,000 eggs every few days after that.

The outlook is grim, though not entirely hopeless. Studies show that native fish rebound by up to 70% of original numbers when lionfish are eliminated. And there is still one market participant powerful enough to take on lionfish: humans.

A slew of areas now have lionfish-catching diving derbies. And it turns out lionfish is actually pretty tasty. Though some fear they contain a toxin called ciguatera, no incidents have ever been reported, and the science isn’t certain. That might mean the only way out of the US’s lionfish catastrophe may be to create a new market—for lionfish ceviche.