In his 2008 book Blood and Rage: A Cultural History of Terrorism, the historian Michael Burleigh observes in passing that jihadist martyrdom videos have a similar structure to porn movies. He doesn’t dwell on the point, although he does allude to the climactic “money shot”: in the jihadist case, the moment when the bomber detonates his explosives.

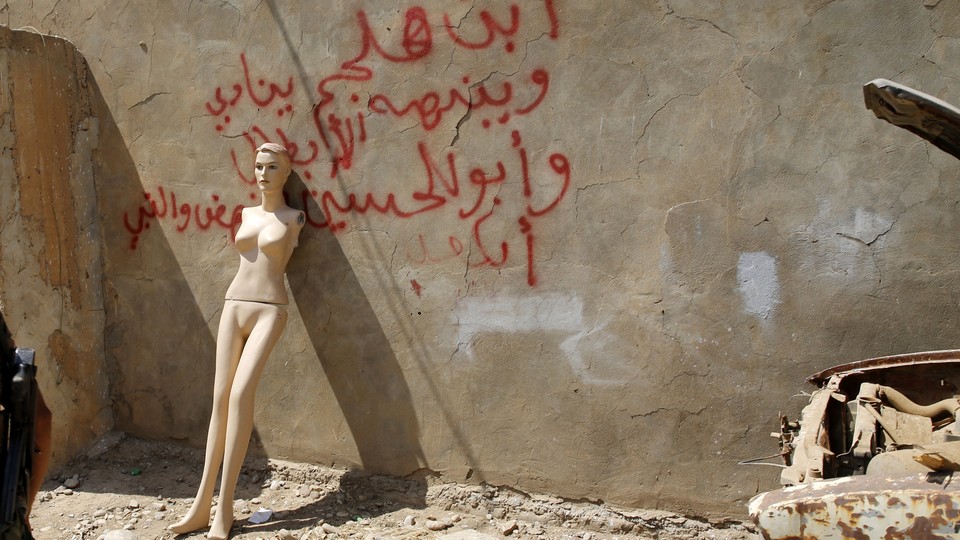

In light of the many ISIS propaganda videos that have circulated this summer, Burleigh’s point deserves further analysis and refinement. One of the most striking aspects of the more violent among these videos—especially the beheading videos of journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff—is their pornographic quality. They are primal and obscene and gratuitous. And, like most modern porn videos, they are instantly accessible at the click of a mouse. Indeed, ISIS videos have attracted such a large audience online that the State Department recently launched its own YouTube channel to counter their appeal, superimposing words of mocking condemnation over graphic images of ISIS’s brutality, entirely missing the point that ISIS appeals to potential recruits in part because of its exorbitant violence.

Jihadists proclaim a fierce opposition to Western modernity, condemning it as soulless, corrupt, materialistic, and depraved. But this has not prevented them from exploiting modern technological advances in fields from weaponry to communications. Nor, evidently, has it stopped them from watching porn. The stash of X-rated material recovered from Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad after his killing by U.S. commandos in May 2011 may have raised eyebrows among some Western journalists, but it was scarcely news in counterterrorism circles. C. Christine Fair, an assistant professor at Georgetown University, wrote on her Facebook page at the time that the U.S. government “has recovered terabytes of the stuff from terrorist computers.”

In any case, the conventions of jihadists’ hardcore film productions unmistakably resemble those of porn. And just as porn has evolved over time, so too has the jihadist propaganda video.

In a 2001 essay on the American porn industry, the novelist Martin Amis makes a distinction between two types of mainstream American pornography: features and gonzo. “Features,” Amis explains, “are sex films with some sort of claim to the ordinary narrative: characterisation, storyline.” Or, as a porn industry executive explained to Amis regarding features: “We don’t just show you people fucking. … We show you why they’re fucking.” Gonzo, by contrast, doesn’t: “It shows you people fucking,” Amis writes, “without concerning itself with why they’re fucking.” He concludes: “Gonzo porno is gonzo: way out there. The new element is violence.”

Violent jihadist propaganda videos can similarly be classified in terms of features and gonzo, with narrative-rich depictions of typically goal-oriented violence in the former category, and narrative-light displays of ostentatious destruction and killing in the latter.

The origins of jihadist features can be traced to the wave of martyrdom videos that came out of Palestine in the mid-1990s. These productions tended to be long—some running to more than an hour—and obeyed a narrative of revenge in which the weak and righteous ultimately triumph over the powerful and unjust. Invariably, the movie featured a bomber whose family had been killed by the Israelis and who plays the role of avenger and martyr. You knew where he was headed and how it would end, but you also knew why, because the bomber himself would tell you: He would look into the camera and read his scripted testimony.

These videos are commemorative and celebratory, focusing on the life and sacrifice of the martyr, who is lionized for his courage and honor. In The Road to Martyrs’ Square, Anne Marie Oliver and Paul F. Steinberg’s rich ethnography of Palestinian suicide bombing, the authors write, “You will never understand anything about the lure of martyrdom, the centerpiece of intifada cosmology, until you realize that someone who has decided to take that path as his own sees himself not only as an avenging Ninja, but also as something of a movie star, maybe even a sex symbol—a romantic figure at the very least, larger than life.” Martyrdom videos, which command huge audiences in Palestine, are instrumental in promoting and sustaining this whole illusion.

Gonzo productions are of a more recent vintage and appear to have their origins in Iraq just after the American-led invasion in 2003. These videos are short—some lasting no more than 12 seconds—and low-budget, making use of a single camera and only the most rudimentary editing skills, mirroring the rank amateurishness that is a hallmark of gonzo porn. They typically depict IED attacks on American or Iraqi government forces, but they don’t overly concern themselves with why those attacks are happening. Rather, the emphasis is on the spectacle of destruction itself, often replayed over and over, mirroring a technique utilized for the “money shot” in gonzo porn. Reviewing a random sample of videos produced by 10 insurgent groups in Iraq between 2004 and 2006, Arab Salem of the University of Arizona’s Artificial Intelligence Lab and his co-authors reported in 2008 that a large proportion showed IED or rocket attacks. These videos, they wrote, were “often filmed in real-time”—showing attacks as they happened—“instructive ... and low budget.” Nine of the 10 groups they examined produced these kinds of videos.

Like Palestinian martyrdom videos, gonzo “shorts” are in a sense celebratory, but the object of celebration isn’t a human life and its passage into paradise; it is a human death or several human deaths. There is an overtly sadistic element to these videos, a glorifying of destruction for its own sake. In some, you can hear the enraptured voice of the faceless cameraman, much like in point-of-view gonzo porn movies before and after the finale. These videos are designed to inspire both jihadist foot-soldiers and potential recruits. Much like porn, they also appear tailored to a mass audience with a limited attention span.

ISIS’s visual propaganda crosses, and in some cases combines, the categories of features and gonzo. There are features like the technically sophisticated “Eid Mubarak Greetings from the Caliphate,” where the emphasis is on brotherly solidarity, faith, and Islamic justice. The message in this and similar features centers firmly on the goal rather than the means of jihadist violence, yet all the while the promise of menace—many of the foreign fighters interviewed are brandishing machine guns—is never far from the surface.

In another video, which blurs the feature-gonzo boundary, there is some stunning aerial footage of the city of Fallujah and embedded reportage of ISIS’s recent road to power in northern Iraq. But there are also some truly jaw-dropping montages of executions filmed with the most basic hand-held cameras. This hour-long video fuses the high production values of jihadist features with the raw and anarchic spirit of gonzo.

And then there are ISIS’s out-and-out gonzo productions. These are short, low-budget, and decidedly thin on narrative. The Sotloff video released in September is the latest example of this shocking genre. In both this and the Foley video, the executioner gives a brief explanation for what he is about to do—“I’m back, Obama, and I’m back because of your arrogant foreign policy towards the Islamic State, because of your insistence on continuing your bombings”—but the focus is less on the rationale than on the grisly act itself. It is no accident that the killer in each video beheaded his victim with a short blade and deployed the sawing motion favored by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq who was killed in a U.S. airstrike in 2006: demonstrations of raw fanaticism, power, and unrestrained brutality. It is a paradigmatic example of what Mark Juergensmeyer has described, in his book Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence, as “performance violence”: a public, theatrical, “symbolic statement aimed at providing a sense of empowerment,” and not at achieving any strategic goal.

In recent months, there has also been a proliferation of amateur violent propaganda from ISIS and its supporters, ranging from photographs of bodily mutilation to grainy videos of executions filmed on cell phones. This visual and sickeningly macabre material is made and distributed by ISIS fighters themselves and represents a purer kind of gonzo. A few weeks ago, for example, Abdel Majed Abdel Bary, a 23-year-old British rapper from London whom British intelligence officials suspect may be the masked killer in the Foley and Sotloff beheading videos, uploaded to Twitter a picture of himself holding up a severed head. The caption read: “Chillin’ with my homie or what’s left of him.” Other jihadists have similarly made use of social media to publicize their atrocities.

Zarqawi was a pioneer of this particular brand of gonzo. His network, originally known as Tawhid and Jihad, publicly released more than 10 beheading videos between September 20 and October 7, 2004, in addition to the video, circulated in May of that same year, believed to show Zarqawi himself beheading the American businessman Nicholas Berg. Given ISIS’s promise to behead more Western civilians, these kinds of videos may yet become the group’s signature production.

Like gonzo porn, ISIS’s beheading videos are way out there. But the new element isn’t violence. The new element is degradation. Walter Laqueur, the esteemed historian and luminary of terrorism studies, writes of the “barbarization of terrorism,” where the enemy “not only has to be destroyed, he (or she) also has to suffer torment.” ISIS represents the apotheosis of this development, completing the degradation of the enemy by filming the whole process. But the group’s propaganda also signifies a new phase in how terrorist acts are communicated and disseminated to the wider world. Forty years ago, the international terrorism expert Brian M. Jenkins remarked that “terrorism is theater.” What Jenkins could not have envisaged at the time was the speed and ease with which images of terror can now be produced and distributed. Nor could he have imagined just how prevalent and grotesquely pornographic terrorist theater has become, and how radically gonzo the groups are who stage it.