At the center of Tara House – a wood-framed compound nestled between a tropical wildlife sanctuary and the Arabian Sea – a verdant garden surrounds an azure pond. Tall palm trees above and slender, vertical wooden slats around the house lend the otherwise-demanding Indian sun a misty quality.

But as soothing as this interior garden space is, the heart of the home – or the “belly button”, as it has been described – is below, down a shadowed stairway. There, a stone-lined chamber has been tightly built around a tidally influenced pool. Rings of light dance upon the water courtesy of air holes that puncture the garden above.

With the sound of the ocean beyond and the pulse of the aquifer below, this cavern seems hewn out to serve as a powerful reminder that, like our bodies, our livelihoods are premised upon water. An estimated half of all Indians lack plumbing.

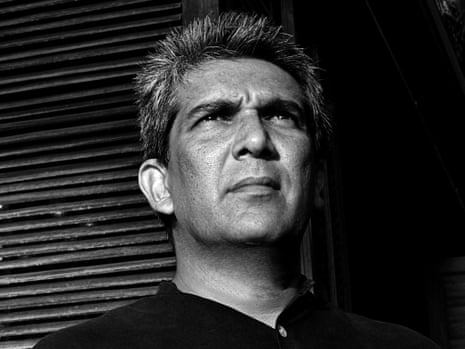

“You develop a relationship via sight, smell and condition, which in turn becomes a way of caring,” Bijoy Jain, the compound’s architect and founder of the increasingly influential Studio Mumbai, said recently.

Jain is US-trained and spent the early years of his career in Los Angeles and London. He recalls those years as a time of personal pain, when he began to see everything that was possible but as yet remained beyond his ability to realize.

Upon returning to India to practice architecture, Jain found he needed a better way to communicate with the stone masons and carpenters, who often could not read an architectural plan. He added the construction of large-scale mockups to the design-build process, creating an inclusive, collaborative way for workers in different trades to handle materials, sketch out ideas and negotiate obstacles together.

“That’s why our studio was initiated,” Jain says. “There will always be the limitations, the question is how does one find the space to operate within that.”

Jain opened Studio Mumbai in 1995 and quickly gained attention, receiving the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture from L’Institut Francais D’Architecture in 2009 and the third BSI Swiss Architectural Award in 2012.

Presenting the Swiss award, noted Swiss architect Mario Botta praised the elevation of craft skills within Studio Mumbai at a time when the forces of globalization are so often interpreted as “a form of standardization rather than an opportunity for interaction and enrichment”.

In fact, it is just this elevation of those skills, using traditional labor pools and methods, that may best showcase Jain’s commitment to sustainability by avoiding the carbon cost of shipping in experts from abroad or even from across the country.

His interest in local materials is another manifestation of this commitment. Palmyra House, for example, was constructed with traditional building methods and all materials are locally sourced, from the foundation’s stone and sand to the joinery made from an Indian hardwood called ain wood and the ever-present palmyra louvers filtering the light and allowing rich air circulation.

The palmyra palm is considered one of the most important trees on the subcontinent, with as many as 800 documented uses. Not only does it tolerate a variety of climatic conditions, but it provides fruit, medicine, weaving and writing materials, as well as a sturdy trunk for construction that may reach as long as 30 meters.

As well, the house was built on a coconut plantation in a way that avoided the loss of income- and shade-generating trees. (While Western architects must struggle to bring light into a building, Jain’s challenge is frequently just the opposite, to cut the light.) It reflects Jain’s ethic of creating structures that deeply inhabit their environs – rather than seizing space from a landscape – a reflection of his belief that humans don’t enter a space from outside of nature but exist within the matrix.

“When I’m referring to nature, I’m referring to man and nature as being reversible or part of the same entity,” he said. “It’s very personal.”

Jain has told the Wall Street Journal that architecture must be ethical and display empathy, but what that means in practical terms isn’t easily prescribed. Each individual must discover their own “unit of measure”, he says.

“It’s not just a technical measure, it’s also an emotional measure. To find that, you sort of set certain frames that you can then operate within and these have to be carefully adjusted. It’s more of a way of life.”

Italian architect Nicola Scardigno might have been referring directly to Jain’s philosophy and practices when he wrote in the Arts journal earlier this year that “traditional architecture was already sustainable” and that it is “unrealistic to entrust terms like zero-energy development, bioclimatic architecture, eco-buildings, and low carbon footprint with the responsibility of solving the environmental agreement between man and nature”.

There are other lessons to be found in the collaborative approach of Studio Mumbai.

Embracing change, for starters.

Architecture, according to Jain, must first of all “contain life”, and accomplish that in a way that recognizes that landscapes change, people change. Life itself stretches from before birth and reaches forward beyond death into decay.

In fact, a conversation with Jain at his studio space just south of Mumbai, interrupted several times by a strengthening rainstorm, seemed an homage to Jain’s obsession with flux.

Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy has noted that good design must serve the “humble everyday needs” of people. “Indeed,” Fathy wrote in the book Architecture for the Poor, “if these designs are true to their materials, their environment, and their daily job they must necessarily be beautiful.”

Jain’s work achieves both that functionality and a deep reverential beauty.

Conversations continue on how sustainable design and construction in the West can serve those of least means, as an overall reliance on high-end materials and costly green-building certifications frequently price out would-be homeowners with more limited incomes. At the same time, some Westerners are hesitant to relinquish climate control even in the milder months.

Jain dismisses questions about what message architects working in the West can take away from his ideas and designs, however, whether its about social justice or the response to climate change. “The only thing one can do is do the work,” he said. “Whether the change occurs or not is not in one’s hands. One does the work just because it needs to be done.”

Greg Harman is an independent journalist based in San Antonio, Texas.

The sustainable design hub is funded by Nike. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion