Redacted from “Detecting Diseases Early,” spring 2016 UNCG Research Magazine

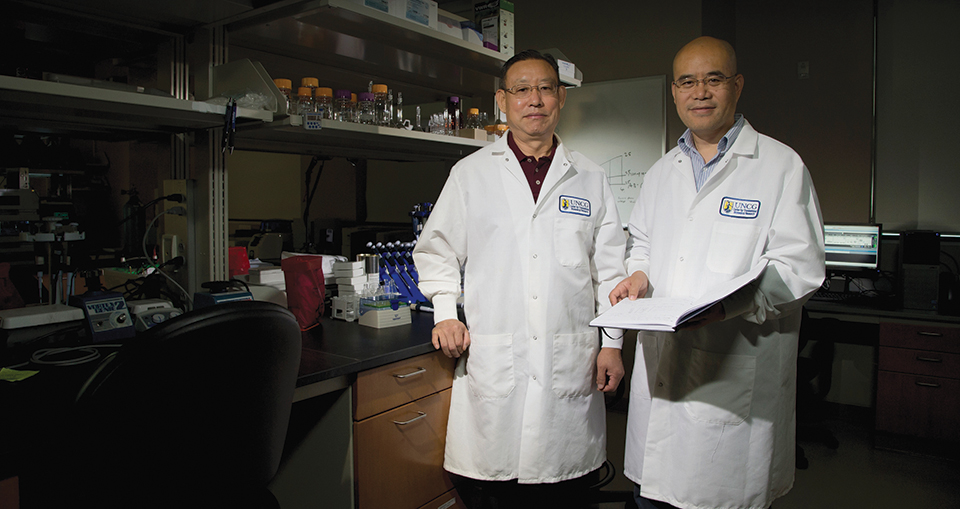

From their lab at the North Carolina Research Campus in Kannapolis, Dr. Zhanxiang Zhou and Dr. Qibin Zhang enjoy a commanding view of both the past and the future.

In the distance sit the modest, low, red-brick buildings of downtown Kannapolis, the city a little north of Charlotte that was once a key player in the state’s textile industry. Immediately below their fourth-floor lab sprawls the bright green front lawn of the gleaming new North Carolina Research Campus.

Built on the site of a massive Pillowtex plant that closed in 2003, creating the largest mass layoff in North Carolina’s history, the 350-acre research campus is the brainchild of David H. Murdock, chairman and CEO of Dole Food Company. The result of a public-private partnership seeking to spur innovation in biotechnology, nutrition, agriculture, and health, the campus involves eight universities and numerous industry partners.

They are all invested in the same dream — that a new era of economic development in North Carolina can arise from the ashes of an industrial past grounded in textiles, furniture, and tobacco.

And UNCG’s Drs. Zhou and Zhang are helping lead the charge.

The research campus is home to UNCG’s Center for Translational Biomedical Research, the 5,500-square-foot lab that Zhou and Zhang co-direct. Both men lead five-member research teams that are funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. They also share a common goal: finding new ways to detect, prevent, and treat devastating human metabolic illnesses that are on the rise globally.

“When you’re talking about something as complex as diabetes and fatty liver disease, it is a lot more challenging to make any progress if the principal investigators work in silos,” says Zhang, who moved his family cross-country to team with Zhou. “There’s a lot of room for collaboration to break new ground, and that’s what has brought both of us here.”

Zhang joined the Center for Translational Biomedical Research in late 2014 after working in the state of Washington for nearly a decade as a researcher at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Biological Sciences Division. With a PhD in analytical chemistry from the University of California, Riverside and a BS in chemistry from Shandong Normal University in China, Zhang also serves as associate professor in UNCG’s Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

Zhou has served five years as a professor in UNCG’s Department of Nutrition. The co-author of a number of articles in prominent scientific journals and the principal investigator of two major NIH projects, Zhou joined the Center for Translational Biomedical Research in 2010 after working as a faculty member in the University of Louisville’s School of Medicine for 12 years. He holds a PhD from Japan’s University of Ehime, having also earned an MS degree at Beijing Agricultural University and a BS at China’s Hebei Agricultural University.

The ultimate research goals of both men are ambitious — and could contribute to major advances in health care. Zhang is pursuing a groundbreaking approach for detecting and treating Type 1 diabetes, which typically impacts children and young adults. It has grown by about 3 percent annually over the past 20 years and now affects nearly 1.5 million Americans. The disease can cause disabling problems, ranging from eye and kidney damage to heart disease and pregnancy complications. The longer it goes undetected, the worse its toll can be.

“Often, by the time you get a clinical diagnosis, a lot of the damage is already under way,” Zhang says. “We need to find out how to spot it and treat it early.”

Zhou feels an equal sense of urgency in his study of alcohol-induced fatty liver disease, which can lead to hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver failure.

In fact, 30 million Americans have some form of liver disease, which is the eighth-leading cause of death in the U.S. according to the Mayo Clinic. “There is no federally-approved treatment for any stage of alcoholic fatty liver disease right now,” Zhou says. “We want to be the first team there. We hope to make a ‘cocktail’ to work on different organ systems to protect against this deadly disease.”

For both Zhang and Zhou, the path to the major breakthroughs they envision is grounded in shared, sophisticated scientific instruments and a collaborative commitment to exploring the biomolecules and mechanisms behind diabetes and fatty liver disease.

Type 1 diabetes stems from the autoimmune destruction of insulinproducing beta cells in the pancreas — and typically begins with asymptomatic periods that can stretch for months or years, allowing the disease to take root unannounced. Currently, there are only limited ways to identify people who are at increased risk for T1D, as the disease is known by researchers. There’s a desperate need to identify more specific biomarkers that can tip off medical professionals to the presence of T1D and how it develops.

Using mass spectrometry-based measurements of human blood samples, Zhang and his team have zeroed in on a panel of unique serum proteins that are linked to immune response and can distinguish T1D from healthy controls with high accuracy. The Zhang team’s next move: extending its biomarker discovery effort to human pancreatic tissues obtained from T1D organ donors. The team is examining blood samples collected during different stages of T1D to comprehensively identify proteins that correlate to the progression of the disease. If they can identify which proteins show up in the earliest stages of T1D, one day doctors may be able to identify T1D so early that therapeutic strategies could be administered in time to reverse the condition entirely.

Zhou, meanwhile, has garnered more than $4 million in federal research grants — and his team gets results that earn attention in top scientific journals. The team contributed an article this year in the Journal of Hepatology about a potential treatment for alcoholic liver disease. Last year, Zhou published a piece in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research that established a connection between niacin supplementation and lowering the lipid levels that correlate with liver disease. His research has also explored the positive impact of zinc supplements on reducing liver lipid levels.

Zhou and his team are also exploring alcohol-induced fatty liver disease from the perspective of the gut-liver axis, specifically looking at the effects of alcohol on other internal organs such as the intestines and how that could lead to inflammation and fat accumulation in the liver. Their work investigates, too, how to stimulate specific enzymes responsible for detoxifying the liver, part of an effort to search for dietary and pharmaceutical approaches to treating liver disease.

“Our findings strongly support a novel concept — that accumulation of free fatty acids in the liver can produce lipotoxicity, which is a metabolic syndrome that is very damaging and potentially fatal,” Zhou says.

Currently pursuing a second five-year grant from the NIH, Zhou and his team want to build on those findings. Their goal is to understand how chronic alcohol exposure leads to the accumulation of free fatty acids and how those acids can induce toxic reactions in the liver.

As their teams delve ever deeper into these research projects, Zhang and Zhou continue to learn from each other, sharing not only their spectrometers, centrifuges, and other high-tech instruments but also their hard-won expertise in chemistry, biochemistry, and nutrition. They both hope to take their work to a new level in the next few years — collaborating with clinical research centers and biotechnology companies on developing medicines with the potential to make a difference in the lives of millions of people globally.