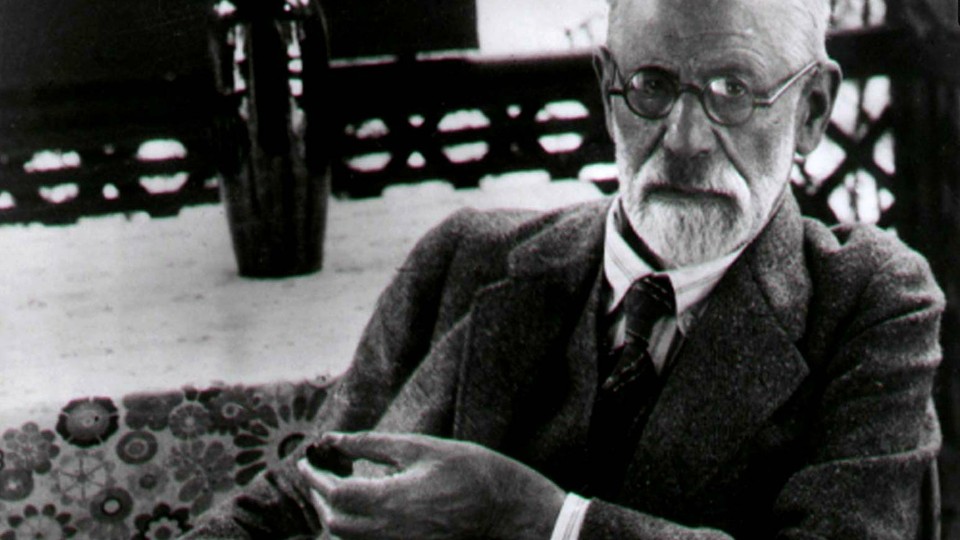

How Sigmund Freud Wanted to Die

Anecdotes from his doctors reveal that the famed psychoanalyst's request has echoes in today's assisted-suicide debate.

In 1956, Dr. Felix Deutsch was invited to Boston to address the American Psychosomatic Society and offer reflections on Sigmund Freud’s 100th birthday. He asked the assembly to consider the following question: “How much and when shall a patient be told about his condition, about the nature of his illness and the threat to his life he has to face?” Deutsch then described how in April 1923, his 67-year-old patient said to him, “Be prepared to see something that you will not like.” Standing at the podium, the doctor recounted what happened after he looked into Freud’s mouth.

“At the very first glance,” Deutsch told his attentive audience, “I had no doubt that it was an advanced cancer. To gain time I took a second look and decided to call it a bad case of leukoplakia, due to excessive smoking.”

It wasn’t leukoplakia, a pre-cancerous condition. Deutsch knew immediately that it was an epithelioma, a more dire, malignant cancer. Thirty-three years later, he addressed his colleagues and tried to convince them why he had prevaricated.

Deutsch began by explaining how physicians of his era feared doing more harm than good by using the dreaded word, cancer, and that concealment of a “bad” diagnosis was commonplace. At the time, physicians made unilateral decisions as to how much they would disclose and what course of treatment to provide.

Deutsch correctly identified the type of cancer, but he incorrectly sized up the man. He had recently witnessed Freud’s intense grief following the death of a beloved six-year-old grandson from tuberculosis, and he told his audience that he feared the truth might give Freud a heart attack.

Freud had also previously inquired about Deutsch’s willingness to help him if he was suffering to “disappear from this world with decency.” Freud was an admirer of the philosopher-physicist, Joseph Popper-Lynkeus, and Deutsch read to his Boston audience a few sentences from a Lynkeus book, The Duty to Live and the Right to Die: “The knowledge of always being free to determine when or whether to give up one's life inspires me with the feeling of a new power and gives me a composure comparable to the consciousness of the soldier on the battlefield …”

The physician blundered further when he involved six of Freud’s closest intimates in a conspiracy of silence. The men had assembled at Freud’s home to confer about psychoanalytic matters and Deutsch confided the diagnosis to them. In a letter, one of them, Ernest Jones, wrote, “The chief news is that F. has a real cancer, slowly growing and may last years. He doesn’t know. [It] is a most deadly secret.”

Deutsch concluded his speech to the American Psychosomatic Society by saying, “I believe it paid not to have told him the diagnosis ‘cancer’.” He then grudgingly admitted, “Freud, however, did not share this opinion when we talked about it in later years.”

Helene Deutsch recounts in a memoir that her husband came home following Freud’s first surgery and remained alone in his study until 4 o’clock in the morning, when he finally emerged to speak with her. She wrote, “Felix resigned from his position as Freud’s personal physician with the explanation that a doctor’s most important possession is the full confidence of his patients and that he had obviously lost Freud’s ... Freud was angry because he believed my husband had underestimated his strength.”

Later, when Jones finally confessed to Freud that their small group had discussed the cancer with Deutsch and agreed to not disclose the diagnosis, an enraged Freud demanded, “Mit welchem Recht?”—“With what right?”

It was not until 1969 that Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross would write about the harm done to patients with cancer by healthcare professionals who do not honestly address the severity of the disease. Patients often know the extent of their health and whether or not they are dying, she wrote. Kubler-Ross made her observations at a moment in which American society began to reject the paternalism of previous generations and to question false reassurances by medical authorities. Freud had arrived at these same conclusions decades earlier. After Deutsch’s firing/resignation, the news was rapidly broadcast among Freud’s intimates that the professor needed a new doctor.

* * *

In 1926, a young internist named Max Schur began providing medical care to Princess Marie Bonaparte, who had come to Vienna to be analyzed by Freud. The princess later suggested that Schur would be an excellent replacement for Deutsch. Afterwards, Schur wrote in considerable detail about his interview with Freud.

During that meeting, Freud informed the young internist (40 years his junior) about two elements of the doctor‑patient relationship that he considered essential. The first was that they always tell each other the truth. The second was “that when the time comes, you won't let me suffer unnecessarily.” Schur readily agreed to these conditions.

Over the next few years, Schur supervised Freud’s medical treatment and arranged his various surgeries. Schur and his patient spoke often about the international financial depression and the rise of Nazism in Germany. Freud was aghast to see what was happening to “the home of Goethe and Kant.” Shortly after Hitler came to power in March 1933, all Jewish analysts, including Freud’s sons, had to flee Germany or face extermination. Austrians began to worry that the Nazis would take over their country, too.

On May 6, Freud’s birthday, Schur came for a house call. Schur’s wife, Helen, was pregnant and uncomfortably overdue with their first child. Freud urged him to hasten back home, and remarked, “You are going from a man who doesn’t want to leave the world to a child who doesn’t want to come into it.” Three days later, Peter Schur was born, and Freud gave the parents a gift of several gold Austrian coins.

On May 10, the newspapers reported widespread burning of Freud’s works by crowds of Nazi sympathizers. As books were fed into fiery pyres the mob loudly chanted, “Against the soul-destroying overestimation of the sex life─and on behalf of the nobility of the human soul, we offer the flames the writings of Sigmund Freud.”

Freud’s cancer remained relatively stable until 1936 when new malignant tumors spread on his palate and required aggressive surgery. 1937 was punctuated by more cancer and further procedures. In 1938, Freud’s surgeon determined that part of the carcinoma was now inaccessible.

In February 1938, Hitler issued an ultimatum to the Austrian chancellor to capitulate or be invaded. Schur went to the U.S. embassy and applied for a visa, and he urged Freud to leave the country immediately. Freud ignored his advice, and on March 11 the German army invaded and rapidly annexed Austria. Nazi flags fluttered in front of many residential homes. Thugs clad in brown shirts and marauding hooligans wearing swastika armbands assaulted Jewish stores, synagogues, and homes, and there ensued a wave of attacks and murders. This was followed by a virtual epidemic of suicides, and during the spring, some 500 Austrian Jews killed themselves in order to avoid further humiliation and assaults.

Shortly following the Nazi occupation of Austria, Anna Freud asked her father, “Wouldn’t it be better if we all killed ourselves?”

Freud replied, “Why? Because they would like us to?”

Anna feared that she and her brother, Martin, would be arrested. The two younger Freuds quietly met with Schur, who gave them a sufficient amount of a barbiturate to be able to choose suicide over torture or internment in a concentration camp. He promised them that he would take care of their father as long as he could.

The Gestapo believed psychoanalysis was part of a Marxist leftist and Jewish conspiracy, and that Freud and his family were potential ringleaders. The Gestapo searched Freud’s home twice and on the last visit insisted that Anna accompany them to their headquarters. She was escorted outside to a big black touring car that had two heavily armed officers in front and two in the back. Martin recalled, “Far from showing fear, or even much interest, she sat in the car as a woman might sit in a taxi on her way to enjoy a shopping expedition.” Concealed amidst her clothing was the barbiturate obtained from Schur.

The Gestapo drove away with Anna at noon. Seven “endless” hours later, she returned, shaken, but unharmed. Schur was with Freud throughout that terrifying time; the two men talked and paced around the house while Freud smoked cigar after cigar. When Anna safely walked into the house, he wept and declared they must all flee Vienna.

* * *

Following Anna’s release from Gestapo headquarters, Freud prepared a list for the British Consul in Vienna of the 16 people, including four members of the Schur family, that he wanted to accompany him to England. Through the combined efforts of Ernest Jones, Marie Bonaparte, and others, they were able to arrange exit visas and permit papers, and the group was permitted to travel to London.

The British government allowed Schur to act as Freud’s physician even before he passed the required national medical examinations. In February 1939, Schur discovered another malignant lesion and deemed it inoperable. Freud started radiation therapy.

Although Freud continued to see a few analytic patients, his condition markedly deteriorated, and Schur moved into his home. Freud adored his pet dog, a chow named Lün, but now the smell of necrotic bone from his jaw was so repulsive that the animal howled and refused to stay in the same room as the master. During the final six months, Anna attended her father constantly, and she woke several times each night to apply a local anesthetic. He was confined to bed and entirely dependent on her care.

Over a span of 16 years, Freud had undergone 30-some operations and several courses of radiation therapy. During much of this time, Freud was reduced to wearing a hideous, denture-like prosthesis to keep his oral and nasal cavities separated, and this device prevented him from eating and speaking normally. Following the first series of surgeries in 1923, he became deaf in his right ear and shifted his analytic couch from one wall to the other so that he could listen with his left ear. Nevertheless, he continued to see patients. In London, he had four patients in treatment, and he only disbanded his clinical practice two months before his death. During the final days, Freud requested that his bed be brought down to the study so that he could be near his books, desk, and beloved collection of antiquities.

On September 21, according to Schur’s first-person account, Freud reached out, grasped him by the hand, and said, “My dear Schur, you certainly remember our first talk. You promised me then not to forsake me when my time comes. Now it's nothing but torture and makes no sense any more.”

Schur said he had not forgotten. He wrote that Freud “sighed with relief, held my hand for a moment longer, and said ‘I thank you,' and after a moment of hesitation he added: ‘Tell Anna about this.' All this was said without a trace of emotionality or self‑pity, and with full consciousness of reality.”

Schur continued, “I informed Anna of our conversation, as Freud had asked.” She reluctantly agreed, thankful her father had remained lucid and able to make this final decision.

Schur wrote, “When he was again in agony, I gave him a hypodermic of two centigrams of morphine [approximately 15 to 25 mg]. He soon felt relief and fell into a peaceful sleep. The expression of pain and suffering was gone. I repeated this dose after about 12 hours. Freud was obviously so close to the end of his reserves that he lapsed into a coma and did not wake up again.”

Freud quietly died at three in the morning of September 23, 1939, 75 years ago. Three days later, his body was cremated. Freud’s ashes were placed in an ancient Greek urn that had been a gift from Marie Bonaparte. Freud bequeathed to Schur his pocket watch, which in turn was passed along to Schur’s children and their children in perpetuity.

The world that Sigmund Freud left behind became increasingly tumultuous as the German blitzkrieg tore through Europe, and both of Freud’s doctors immigrated to America. Max and Helene Deutsch settled in Massachusetts and became faculty members and training analysts at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute. Felix Deutsch died in 1964.

Max Schur and his family booked passage on the S.S. President Harding for New York City, where he reestablished a private internal medicine practice. A cardiologist, Dr. Steven Wittenberg, describes Schur as being, “an avuncular figure, who not only cared about his patients’ health but also offered them and their families a remarkable degree of emotional support and counseling.” Schur and his wife became training analysts at the New York Psychoanalytic Society and faculty members at the State University of New York’s Downstate psychoanalytic program in Brooklyn. He developed a cardiac condition, but refused to be hospitalized and died in his home in 1969.

His son, Dr. Peter Schur, is now 81 years old, a Harvard Medical School professor of medicine and senior physician in medicine and rheumatology at Brigham & Women’s Hospital. “Euthanasia,” he explains, “was not uncommon, but nobody talked about it.” In a recent interview, Peter Schur said he was proud of his father’s treatment of Freud and believes, “You should give patients the opportunity to explain just how they want to die.”