Atlantic editor Scott Stossel: "I'm platform agnostic"

Scott Stossel, editor of The Atlantic, has reason to be nervous. That’s partly because of his personality—detailed in “My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind” published earlier this year—but also because the venerable print magazine over which he presides is just barely in the black. Stossel, who describes himself as “platform agnostic,” is on his second tour of duty with The Atlantic. After joining the staff in 1992, he helped launch The Atlantic Online, the title’s initial digital venture. He worked at the American Prospect from 1996 to 2002, when he returned to The Atlantic.

Founded in Boston as The Atlantic Monthly in 1857 and now based in Washington, D.C., the magazine is successful both online and in print. While print circulation has grown to nearly 500,000, the number of unique monthly visitors to TheAtlantic.com hit a high of 16 million this spring. Parent company Atlantic Media has launched two successful spinoffs, CityLab (formerly The Atlantic Cities) and The Wire (formerly The Atlantic Wire). Stossel spoke with Rachel Emma Silverman, a 2014 Nieman Fellow, during a visit to Lippmann House earlier this year. Edited excerpts:

On getting to profitability

When David Bradley, a Washington guy who had built consulting companies and sold them for hundreds of millions of dollars, bought the money-losing Atlantic in the late ’90s, he thought, “Oh, I’m a business genius. I’ll now do this with media.” And as many business geniuses learn when they turn to media, it’s a lot harder to make money in that than in just about everything else, except maybe restaurants.

To his credit, he invested an enormous amount of money very early on. The magazines got fatter. We got nationally prominent writers writing for us. We started winning more National Magazine Awards, and we were hemorrhaging millions and millions of dollars a year. Then he hired Justin Smith, a relatively young media veteran who had worked at The Economist in Asia and had developed The Week’s business strategy. David sold him on, “Look, what we have is this venerable tradition, but we can reinvent it.”

Justin did two things that were very, very smart. The first thing—that was painful—was he radically cut costs. When advertising dried up—and this was in the teeth of what was already a major decline in print advertising—we had to tighten our belt, but it was less dramatic than at a lot of publications. Two, he said, “We need to in this age be digital first.” And that meant investing in technology, investing in Web editors, hiring bloggers.

“The print magazine and online are both profitable, but the digital revenues are growing much, much faster”

Concomitant with all of that was we refined the brand. We brought in a brand consultant and all these marketers. At the time, it felt a little bit squishy and bogus, but I have to say it was a useful exercise to think very deeply about what is our core DNA. For us, it’s ideas journalism, covering the world of ideas. We extracted this core DNA and then thought, How do we carry it into events and online? In 2010, we actually did break even, very narrowly. We’re not making a huge profit, but we have managed to keep our heads above water every year since then. The print magazine and online are both profitable, but the digital revenues are growing much, much faster.

On the economics of print

My hope is that we’ll continue to get enough print advertising to invest in the print product. But I’m platform agnostic. In fact, if we could suddenly convert our 500,000 print subscribers—all of them pay, even though all the content is free on the Web—to digital subscribers and scrap the print magazine, our bottom line would be so much better. We could pay writers more because we wouldn’t be paying for printing and mailing. But we can’t force the issue because we’ve got $10 million worth of print subscribers.

On paying writers

Our pay rates for the magazine have come down in recent years, but they’re still considerably higher than our standard rates on the Web. What justifies that? At some point, Web pay rates have to rise and print rates will come down. We have plenty of native digital pieces that are hugely important and really well done, but so much more time goes into the writing, the reporting, the editing, the factchecking, and the design of the print magazine pieces.

If you’re sitting on the corporate floor and you look and say, “We have a 22-year-old kid we’re paying not very much money who can write a post at nine in the morning that goes totally viral and gets all the ads … Or we have these experienced journalists who we’re paying much larger salaries for, and it costs much more money to subsidize their reporting and the whole apparatus around producing that piece. Gee, shouldn’t we get rid of all those expensive ones and just do more of that?” Sometimes there has been that tension, but I think there’s a realization that you need both. Again, this gets back to brand, that our brand is associated with rigor, length, and careful curation. These are questions we struggle with.

On cover stories

The cover story is the most important thing we do in the magazine because it drives newsstand sales, which aren’t necessarily the most important, but it drives mindshare, and people remember “The Organization Kid” or “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All.” There’s a weird vestigial thing even as we’ve moved into the digital age. A lot of what drives attention to a cover story is whether you get broadcast media, NPR or the morning shows. For the producers of “Meet the Press” or “Good Morning America” or “Morning Joe,” what’s on the cover matters. The mere fact of being on the cover means that producers book our writers on shows. Again, that’s probably a lagging indicator, left over from some old version of the journalistic system, but it matters a lot.

On brand-name bloggers

We brought in a bunch of superstar bloggers, Andrew Sullivan being the most prominent, but also Ross Douthat, who then migrated to The New York Times, Marc Ambinder, Matt Yglesias, and various others, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, who’s still around. We’ve realized that it’s cost-effective to do so. We really want people to exist within The Atlantic brand. They can have their own brand but it needs to be aligned, we all need to be moving in the same direction. The problem we’ve had lately is we’ve hired some 22-, 23-, 24-, 25-year-olds who become so good that they immediately start getting poached and their salaries get higher and higher so we try to strike a balance there.

On verticals

We try to grow TheAtlantic.com organically by building up these verticals and doing things that bring in more traffic. When we changed the name of The Atlantic Wire to The Wire, traffic plummeted because it changed how Google ranked us. We’ve now gotten it back up to where it was but it took six months. What The Wire does is very different from what TheAtlantic.com does. There’s not a lot of original reporting, but it gives you everything succinctly with a little bit of voice and some edge.

I’ve talked to foreign journalists who say that when they are trying to figure out what stories to put in their broadcast in Colombia, they’ll just read The Wire. And they’re covering the coverage, too, so they’re telling you this is what The Washington Post and The New York Times are saying, this is what’s in the gossip pages. That’s an experiment of launching a sub-brand that we think will prove to be successful.

We’re trying to expand Atlantic Cities [now called CityLab] out of wonky urban policy stuff into lifestyle and restaurants and that kind of thing. We saw this as a smart advertising play, but we’re never sure. We’re always debating: Is this better housed as a vertical within The Atlantic.com or should it be hived out?

On gender and racial parity

All of the senior editors who have been promoted or hired over about the last year and a half were women. In each case, I can sincerely say they were the best candidates for the jobs. They’ve all worked out terrifically. On average, I think, the typical female editor has somewhat more female writers in her Rolodex than the typical male editor does. And I think that having more senior female editors has been good for us, both culturally and in terms of the magazine.

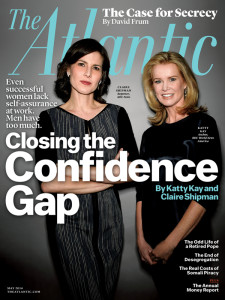

Every year we get dinged, along with our peers, in VIDA reports about male versus female bylines. To some degree, we can exert change on the world, but if you take the world as we receive it, the reality is—I’m making this number up, but it’s not crazy wrong—the number of submissions we get probably skews 8:1, male to female. For every submission from a woman, we get eight from a man, which may suggest that—Katty Kay and Claire Shipman talk about this in “The Confidence Code”—men are much more willing to bloviate about things they don’t know anything about. There’s a pundit gene where they feel like they have something to say.

We have a similar issue, which is in some ways more acute across the industry, with racial diversity. We happen to have one of the best African-American journalists writing today, Ta-Nehisi Coates, but also we have three people of color in the entire organization. There’s a whole host of reasons why that is, and we have for some years done aggressive outreach to try to rectify that. But it matters not just in terms of equal opportunity and justice, but in terms of the perspective that you bring to different stories.

We do think about it. It is improving, but we’re still confronted with this 8:1 ratio. We can change that by actively seeking out more. Our last two cover stories were by women. There’s also the problem of, well, why are all of your female byline cover stories about women’s issues? And yes, we’re guilty of that. Again, not by design, but it tends to turn out that way.