Recently I had the incredible fortune of facilitating a Theatre of the Oppressed institute for teenagers. Working with young people is a particular joy of mine, especially with their capacity to reach for concepts usually reserved for academics. I’ve been studying Theatre of the Oppressed for years, participating in workshops and master classes. But explaining my views on theatre to these young people, I learned that Theatre of the Oppressed provides a great (and simple) model for improving the theatre community at large and reversing many of its inherent injustices. What is Theatre of the Oppressed, you ask? I should start at the beginning.

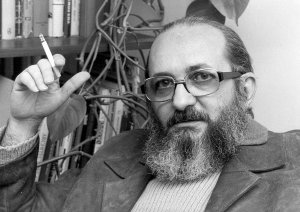

Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the landmark work by Brazilian educator Paolo Freire, was first published in 1968. It is the the work credited with jumpstarting the critical pedagogy movement, a movement which would question the assumptions of not only the content of our educational system, but also the very techniques used. Among other conjectures, the book argues that the way we teach and what we teach (and therefore how and what we learn) is the reflection of a colonial history. In turn, those educational modes colonize the minds of the oppressed. This was highly relevant to Freire, who understood the experience of many Brazilians as continuing to represent the racial and economic structures of Portuguese colonization. The book is a courageous and radical criticism of the oppression inherent to society in Brazil, and around the world. So challenging were the ideas within that “most totalitarian states—risked cruel punishment, including imprisonment, if they were caught reading Pedagogy of the Oppressed.”

But perhaps the greatest contribution that Freire made was the notion that the most effective way to counteract oppression in education was to stop treating students like empty piggy banks waiting to be filled, or like the teacup in the zen koan. Rather, he opined, learners should participate in the creation of knowledge. They should have agency in what it is that they learn, so that they cannot be forced to swallow ideas that would lead them to believe that they are lesser than others, or somehow deserving of oppression. This is the idea that Brazilian theatre artist Augusto Boal used to develop the Theatre of the Oppressed, which, more than an international organization or ideology, is a collection of techniques and perspectives that aim to bring this idea to theatrical practice.

Likely the most notable element of Theatre of the Oppressed is Forum Theatre. Forum Theatre is a staging technique wherein the audience, as “spect-actors”, can stop a performance and change a choice or the path of the narrative by interjecting themselves. This can be particularly demanding because it requires actors who are open to being interrupted, to trading places, and to taking direction from sources external to their original process. This allows the audience to deconstruct situations and change their outcome, allowing them to develop their own strategies for combating/resolving whatever oppression is evident in the narrative. It also gives them a participatory insight into how hard it is to change even momentary oppressions. Usually, this process is guided and interrogated by a neutral facilitator which Boal refers to as the Joker, who asks questions but never comments or intervenes.

Envision, if you will, a stage raised only eight inches from the rest of the room, where three actors strut and fret through a scenario: Ernest and Karina (an interracial couple) walk down a busy street hand-in-hand where a catcaller harasses them, commenting with vulgarity on Karina’s dress. Ernest, to Karina’s chagrin, confronts the man. This confrontation ultimately ends in violence. A fourth actor climbs onto the stage, and arrests Ernest for his part in the violence. End scene. Here, the Joker, stepping out from his place beside the stage, asks questions like:

1. What about this scenario is representative of oppression?

2. What did you think of the choices that were made?

3. Why did the police officer arrest Ernest?

4. Was anyone in the wrong? Was anyone in the right?.

5. What is the root of the problem?

The questions can vary widely, as long as they do not openly indicate judgement. The audience responds, and the Joker acknowledges their responses without agreeing or disagreeing.

Then, the Joker invites the audience to watch the scene again, but this time, they may raise their hands and stop the performance, take the place of any one of the actors, and take choices that they believe will change the outcome of the scenario. Then, Ernest and Karina walk down a busy street…

It’s easy to ask “what’s the value of that?” It has to do with the general nature of theatre in the modern Western canon. Most theatre the average viewer will see will be a narrative played out on a stage where the audience is physically and ideologically separated from the actors. The viewers, engaged in artistic voyeurism, receive the message portrayed by the actors. As anyone who works in theatre knows, the content of that message is often determined by the people or organizations which fund plays. While theatre-goers actively participate in funding through the purchase of tickets, in traditional theatre they have no way to actively participate in the content of a performance.

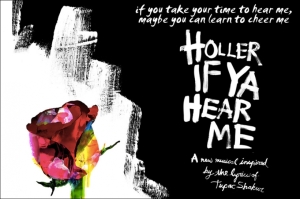

I’m not suggesting that this is always a bad thing. God forbid that every audience member be invited on stage during Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and I can feel my blood pressure rising at the thought of the average Broadway audience member on stage, changing the narrative of Holler If Ya Hear Me or attempting to rap along. But I see theatre as largely a tool for social change, something that can present ideas on emotional and intellectual levels simultaneously, and so, the same old same old doesn’t really cut it in that regard. Even if the techniques of Theatre of the Oppressed aren’t always called for, the approach practically always is.

I’m not suggesting that this is always a bad thing. God forbid that every audience member be invited on stage during Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and I can feel my blood pressure rising at the thought of the average Broadway audience member on stage, changing the narrative of Holler If Ya Hear Me or attempting to rap along. But I see theatre as largely a tool for social change, something that can present ideas on emotional and intellectual levels simultaneously, and so, the same old same old doesn’t really cut it in that regard. Even if the techniques of Theatre of the Oppressed aren’t always called for, the approach practically always is.

How often when watching a television show, or a movie, do we wish that we could step in and change some action? Keep Supernatural’s Dean Winchester from making another self-destructive choice? Stop someone from going in to a room because you know there’s a murderer in there, or keep Ned Stark from trusting Petyr Baelish, because Petyr told him not to trust him? Isn’t that why we write fanfiction, to envision something differently and better? Forum Theatre is designed to give the theatre-goer exactly that kind of agency, allowing them to question the choices and the structures that lead a certain situation to go a certain way. That’s powerful in and of itself. But the idea is even more powerful.

The fundamental question is: what are the ways that theatre artists and theatre audiences can give voice to those typically excluded from the narrative process? The first step is to ask “who gets to write the stories, and why?” Of course, then we have to ask “who doesn’t, and why not?” Finally, we must ask “how do we change that?” This is probably the most important argument currently being had in theatre circles, and it’s not academic. Conjectures are being made and questions asked every time a theatre company endorses colorblind casting, and every time a playwright rails against it. It happens every time a theatre chooses to stage Suzan-Lori Parks’s Venus or her upcoming show Father Comes Home from the Wars instead of their tenth production of My Fair Lady. It also happens every time the opposite occurs. That’s the lesson we get from Forum Theatre’s approach: to critique who is and isn’t a part of our storytelling.

Storytelling is everything. How we talk about our history and what goes into history books is storytelling. Who gets to act in which movies and in which plays is a question of storytelling. Who gets elected, or becomes the leaders who make choices about our future, has a direct effect on what will one day be storytelling. So, by engaging people and peoples who have traditionally been discounted or excluded from the storytelling, we change the story. Better yet, we make an opportunity for new and better stories to be told.

Follow Lady Geek Girl and Friends on Twitter, Tumblr, and Facebook!