The Day ‘Stop the Bleed’ Entered Civilian Life

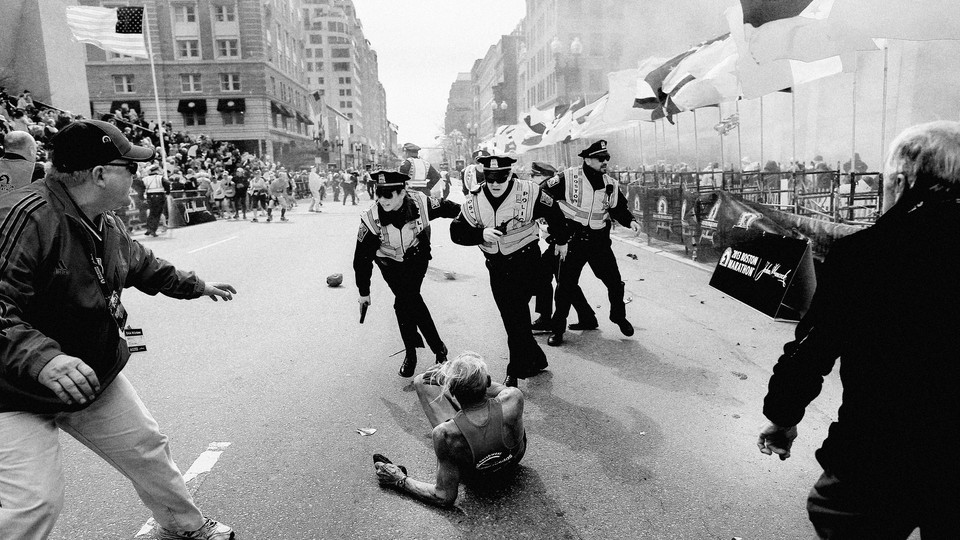

The Boston Marathon bombing changed disaster management.

In a crisis, the best measure of how well a community reacts isn’t the number of lives lost. It’s the number of people who survive. When two homemade bombs went off at the Boston Marathon finish line a decade ago this month, three people died on the scene. But the number of spectators and runners who were treated at local hospitals for injuries, some of them quite severe, was much larger: 278. Improbably, every single one of them survived. The success of any disaster response always hinges on advance preparations—yet those measures can take a wide variety of forms.

The 2013 bombing was a turning point for civilian adoption of a military-inspired technique known as “stop the bleed”—the use of a tourniquet, or a shirt, towel, or some other improvisation, to halt excessive blood flow and buy time until professional medical care is available. More than two dozen of the most seriously injured patients received life-saving field tourniquets on the scene in Boston before being transported to the hospital.

Fortunately for the hundreds of people injured in the explosions, Boston and surrounding municipalities have a high concentration of hospitals that had trained for a mass-casualty event; 26 such institutions received patients after the explosions. Of the victims, 127 were evaluated at Level I trauma centers—the premier emergency-hospital category—on that Monday; 54 of them went into surgery that day. The median time from the explosions to the hospital for an injured patient was 11 minutes.

Although 12 patients underwent leg amputations either above or below the knee, the outcome could have been far worse. Massive bleeding is the most urgent risk to many bomb victims, especially if the devices are placed on the ground and affect victims’ legs and larger body areas. “Stop the bleed” was not always the standard response, not even in war. By 2013, medical procedures had fundamentally changed in the battlefield. When the Iraq War started in 2003, many experts feared that using tourniquets too quickly would lead to unnecessary amputations and mixed results. Early in the war, treatment for some injured U.S. soldiers was delayed until they could be moved to medical facilities. But the military came to understand the need to prevent blood loss on the scene of an injury, and the Pentagon began to modify its training not only for medical personnel but for field soldiers. Over time, the Pentagon invested in blood-clotting medicines, foams, sponges, and even clothing.

“You’ve got four minutes to get someone oxygen so their brain doesn’t start to die. But you really only have a few pumps of the heart before they’ve lost so much blood they’re not going to live,” Colonel Patricia Hastings, a physician and combat-medicine expert, told Medical Xpress in 2011. The effective administration of a tourniquet prevents that. When military officials later reviewed tourniquet use in 499 injured soldiers in Iraq, they found that nearly 90 percent survived, and almost none required an amputation.

These findings began to influence civilian medical and emergency-response training in the United States, and returning former soldiers brought home expertise they had learned in the field. At the marathon, some spectators were medical personnel and veterans who understood that the injuries sustained would not be life-threatening if victims’ blood loss could be quickly limited. These efforts in Boston in 2013 helped fuel new public- and government-awareness initiatives—including a formal Stop the Bleed campaign—about the importance of curbing blood loss, whether from a car accident, a gunshot wound, or any other cause. California just passed a law that requires “trauma bleeding control kits” in all new public and private buildings.

The Boston Marathon and its aftermath transformed disaster response in other ways. The Boston Police Department’s immediate focus on family unification to match runners and their families who were separated in the chaos has become a model for many active-shooter incidents too. Although the FBI, through its most-wanted list, has long sought the public’s help in catching known suspects, the bureau’s appeal for photo and video footage helped launch a new era of crowdsourcing investigations. Then–Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick’s stay-at-home request on the Friday after the bombing, when one of the two suspects remained on the run, foretold the shutdown orders prompted by the coronavirus pandemic seven years later. That frenetic week in Boston left behind some cautionary tales too—including a command-structure breakdown, during the final moments before the bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s capture, that likely led to a friendly-fire shooting of a police officer.

Yet the Boston Marathon’s most enduring legacy is the democratization of “stop the bleed,” which—like the Heimlich maneuver and CPR before it—gives regular people the ability to save lives with a modest amount of training. We can and should be outraged that so many civilians face the kinds of injuries—whether from IEDs or, more often, from mass shooters—that produce sudden blood loss. But being prepared for such events is better than the alternative. You don’t need a medical degree to tie a knot.