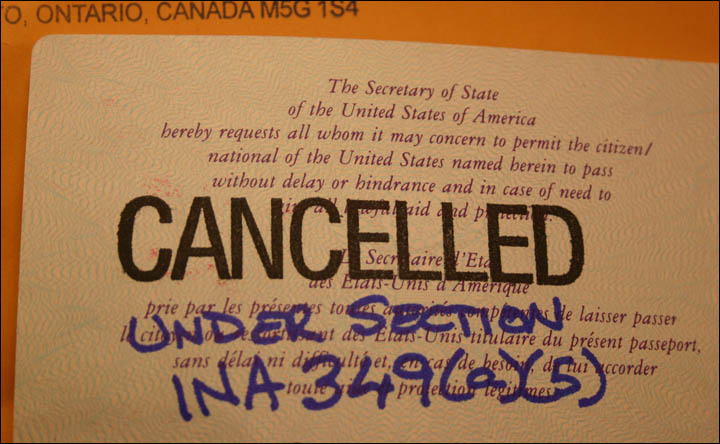

A controversial tax deal with the United States, under which Canadian banks agree to try to find U.S. citizen clients and report them to the IRS, using the CRA as an intermediary, took effect July 1.

But many dual citizens in southern Ontario aren’t waiting to be found – they’ve decided to shed U.S. citizenship. In the process, they’ve created a backlog at the U.S. consulate in Toronto that stretches into the third week of January 2015.

Dundas-based tax and immigration lawyer David Lesperance said on Twitter yesterday that he booked 2014’s last renunciation appointment at the Toronto consulate for a client on Tuesday.

In an e-mail Tuesday, the Toronto consulate said the earliest date they could book for a renunciation is January 22, 2015.

Until recently, appointments to renounce U.S. citizenship in Toronto could be made within three to six weeks, said Toronto-based cross-border tax accountant Kevyn Nightingale, who specializes in tax advice for people giving up U.S. citizenship.

His clients are driven to divorce Uncle Sam less because of actual U.S. taxes and more because of the costly demands of the tax bureaucracy, he says:

“Almost none of them have to pay any tax – it’s just the hassle and expense of dealing with the paperwork.”

Nightingale says he charges $1,000-$1,500 for “very simple” U.S. returns.

“Filing U.S. tax returns is complex, and the reason is that everything that happens to a U.S. citizen in Canada is foreign. People who are able to do their Canadian tax returns easily and relatively cheaply, once you add the foreign layer on to it, ordinary people have problems that need to be dealt with sophisticated tax people.”

Earlier in August, two dual citizens sued the federal government, arguing that the intergovernmental agreement (IGA) to implement the U.S. Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act in Canada violated the Charter.

For U.S. diplomats, people renouncing citizenship are a lot of work compared to other consular tasks, Lesperance points out:

“They are, from a consular officer’s point of view, a fairly labour-intensive exercise. It doesn’t take the four minutes that it takes to register your child as a birth abroad.”

Until recently, U.S. officials required people wanting to renounce to visit the consulate twice – after the first meeting, would-be ex-citizens would be sent away to reflect.

In 2011, the Toronto consulate held the first meeting in a group format to cope with demand.

READ MORE: Dual citizens sue feds over FATCA tax deal with U.S.

The process has since been simplified to one meeting. “I think it’s just pressure of numbers,” Lesperance says.

Update, 4pm: “With the increase in the number of persons wishing to renounce, wait times have at times increased at some posts,” a U.S. State Department official wrote in an e-mailed response. “Some posts in Canada are currently experiencing wait times of five months or longer to execute the Oath of Renunciation.”

Pushing the appointment into next year doesn’t just frustrate the impatient, however – it adds an entire year to U.S. tax reporting. Someone making an appointment now to renounce in Toronto in January wouldn’t be able to log out of the U.S. tax system until June 2016.

However, people can work the phones and find a U.S. consulate that can give them an earlier appointment, Nightingale says:

“If Toronto is booked up, you can go somewhere else. You can go to the Montreal consulate; you can go to the embassy in Ottawa.”

The U.S. State Department estimates that about a million people considered American under U.S. law (who may also be Canadian citizens) live here. In theory, all of them, unless their income falls under minimum levels, are supposed to file tax returns with the IRS, and report their bank accounts to an arm of the U.S. Treasury Department called the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, on pain of heavy fines.

In practice, few did until recently.

- Life in the forest: How Stanley Park’s longest resident survived a changing landscape

- ‘They knew’: Victims of sexual abuse by Ontario youth leader sue Anglican Church

- Carbon rebate labelling in bank deposits fuelling confusion, minister says

- Buzz kill? Gen Z less interested in coffee than older Canadians, survey shows

“The U.S. has always had citizenship-based taxation on the books, but the compliance rate with that was always one hundred per cent voluntary on the part of the person who took it upon themselves to comply,” explains McGill University law professor Allison Christians.

“We know for sure that residence-based taxation is enforceable, and citizenship-based taxation is not enforceable unilaterally. You cannot do it unless the other country steps up to say, ‘We agree. We are going to find people in our country who are of your nationality, and we are going to show you where they are, and we’re going to point you to their accounts.’ That’s what Canada has done with the IGA.”

Canada’s 2006 census found about 300,000 people in Canada self-identifying as U.S. citizens. (The difference may be accounted for by Canadians who were born in the United States, or who have an American parent, but don’t consider themselves American.)

In the meantime, Nightingale warns, the tax side of renouncing U.S. citizenship can be expensive:

“If somebody comes to us and says, ‘I’m a U.S. citizen, I’ve never filed tax returns, I’ve got a pretty ordinary life, but I’ve got an RRSP, an RESP, a TFSA and some mutual funds, and can you prepare all my returns and get me ready for expatriation?’, by the time we do all that, it’s not hard to spend $15,000 or $20,000 for a fairly ordinary person.”

Comments