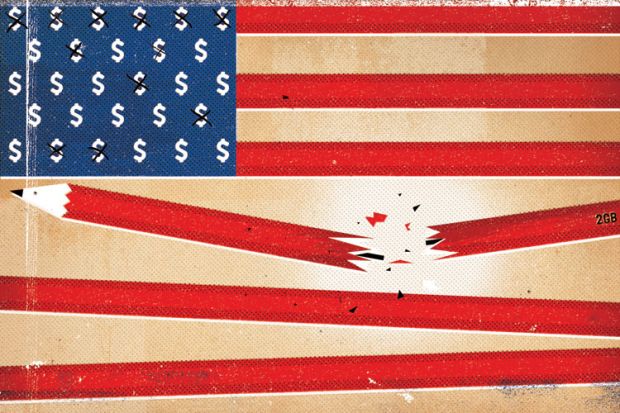

Source: Dale Edwin Murray

To English eyes, the US loans system feels excessively tough. To American eyes, the English system looks excessively generous

Critics of English higher education policy condemn the sowing of American seeds on English soil. But some of these criticisms are so off-target they are counterproductive. No one in their right mind would seek to replicate the US system of funding, and inaccurate rhetoric lets policymakers off the hook.

The narrative of student finance in the two countries may have some parallels, but a closer look reveals that the differences eclipse the similarities.

In the US, federal student loans were an answer to a middle-class problem: how to pay for university when only a few people could afford to go. They were targeted very much at those in the middle, since poorer students were to have scholarships and “work-study” opportunities, while richer students were expected to pay their own way.

In the UK, student loans were introduced much later, in 1990. They were not designed to fund a greater number of middle-class students so much as to make life more tolerable for those already at university. That’s why they were restricted initially to living costs.

A second issue is that of “first-mover disadvantage”. When colour TV was rolled out across the US, the broadcasting standard, NTSC, was so patchy that it became known as “Never Twice the Same Color”. As with TVs, so it was with student loans: America suffered from being first. With private banks as lenders and taxpayers subsidising the interest, the financiers had politicians over a barrel. As recounted in The Student Loan Mess: How Good Intentions Created a Trillion-Dollar Problem (2014) by Joel and Eric Best, when interest rose, they redirected their business elsewhere until politicians raised the subsidies.

Repayment terms were fixed, not income-contingent, and there was no write-off date. Hard-up graduates declared bankruptcy to escape, until this was barred in 1998.

The system also suffered from weak regulation. Slack controls on student loans for vocational education caused considerable leakage during the 1970s.

In the UK, banks have not played the same role at undergraduate level, and repayments have been sensitive to graduates’ incomes. Loans have been more tightly regulated, too. Scandals have occurred but, for once, Brits have had more weapons in their armoury than their US cousins.

Despite these differences, there are clear transatlantic lessons.

The first is on tuition fee inflation. Some argue that fees in England should be allowed to float until they find their natural level. But the US experience suggests that that level is always higher tomorrow than it was yesterday. Tuition fees at not-for-profit institutions in the US have doubled in real terms since 1980.

Those English universities that say it costs much more than £9,000 a year to teach their students have not yet made a sufficiently compelling case. Indeed, the evidence for uncapping fees in England is weaker than that for cost control in parts of the US sector. At present, neither is politically likely.

The second lesson concerns entitlement to loans. The US data show a clear correlation between the likelihood of a student loan being repaid and college type. The three-year loan default rate is 22 per cent at for-profit institutions, 13 per cent at public institutions and 8 per cent at private non-profit institutions. This partly reflects their student bodies, but it is also a result of lax regulation. America could usefully consider how England and Australia have managed to open up student loans to a more diverse range of providers while avoiding the same level of concern about a “bubble”.

But there is also a lesson for England from the US. The coalition famously expects to write off 45p in every £1 loaned to undergraduates. But it expects to write off even more (at least 65p in every £1) of the new loans for further education. Those who worry that the system is unsustainable may have a point, but they ignore the area where the problem is greatest.

The third lesson is on repayments. In the US the preference has been for shorter, sharper repayments. In recent years slower repayment plans, with elements of income contingency, have been offered, but intriguingly have not always proved popular. Longer repayment may limit you when you are trying to buy a house or start a family, and generous income-contingent systems can sometimes seem inferior to borrowers. Student loan systems should incorporate a range of repayment options: it now seems bizarre that the coalition once formally consulted on penalising people who want to repay early.

In the US, graduates who do not repay their loans are sometimes labelled “deadbeats”; in England, they are respected for choosing low-paid work, or pitied for being unable to find a graduate-level job. To English eyes, the US system feels excessively tough. To American eyes, the English system looks excessively generous. The end result is the same: a system that costs more than intended. That is why both countries are now looking to hold institutions to account for graduate performance.

Both loan systems face a similar challenge: how to ensure that student loans are affordable for graduates and for taxpayers.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login