Leandra Ramm is a survivor of a crime that has been called "psychological terrorism". A mezzo-soprano by training, the New Yorker spent most of her 20s trying to escape from the clutches of a cyberstalker thousands of kilometres away in Singapore.

Posing as a director of a music festival, Colin Mak Yew Loong first contacted Ramm in the United States in 2005 and promised to help further her music career. Initially, she was grateful, but when she stopped replying to his messages, realising that he was a fraudster, Mak resorted to threatening e-mails and phone calls. He sent her around 5,000 emails. He also created hate groups on Facebook and Twitter about her, created a blog about her and made rape and physical threats against her and her family members, along with bomb threats against opera companies that engaged her. He also stalked her by proxy; unsurprisingly her promising career quickly collapsed.

Armed with reams of evidence, Ramm went to the FBI, the New York Police Department and other government agencies. All of them said they could do nothing, as the crimes were committed in Singapore. The police in Singapore showed no interest, as the crime of cyberstalking did not exist in that jurisdiction. There is no such thing as an international cyberstalking treaty and so Mak continued to destroy not only Ms Ramm's career, but also started to stalk other women and those linked to them, unchallenged by law, in Singapore and Europe, both physically and in cyberspace. He harassed a Ukrainian musician, Veronica Sakhno, physically and in person, and a Singaporean businesswoman, Liew Hwei Ken, in 2010, to whom he sent death threats, containing images of executions. He cyberstalked Siegfried Geyer, the German boyfriend of a Hungarian musician, Krasznai Tuende Ilona, threatening to castrate him for the crime of being in a relationship with Ilona, in 2011 and 2012. He also issued death threats to them and Geyer's children.

Three women of different nationalities and one man were named in the court papers. The real number of victims may be much higher. Eventually, Mak's stalking cost Ramm her opera career. She contemplated suicide and was diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder. It was only in 2011, when Ramm gathered a team around her and hired a cybercrime expert, A J Fardella, with links to the US Secret Service, who could navigate the American and Singaporean legal system, that things started to shift in her favour. She had to work on a cruise ship for two years to pay the legal bills to mount the case.

Mak pleaded guilty to sending Ramm 31 threatening emails and admitted to 11 other offences, including intentional harassment (of two other women and one man) and criminal trespass, in December 2013. He was jailed for three years. District Judge Mathew Joseph called the matter an "abhorrent case of cross-border cyberstalking", telling Mak: "The virtual internet in your criminal hands became a lethal weapon. It was used as a weapon of massive personal destruction in the real world of your hapless victims." Ramm's case is the first successful conviction of international cyberstalking.

STALKING ACROSS BORDERS

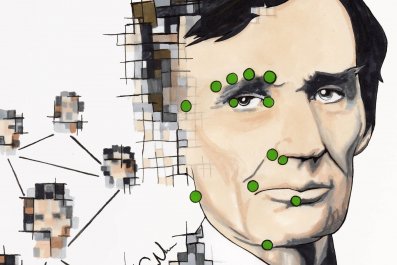

Police and prosecutors say that cyberstalking – the persistent use of the internet, e-mail, social networks, instant messaging or related digital devices to annoy, harass or threaten – is growing, and that they still lack the legal tools to combat it. Cyberstalking falls into three main categories: direct communication, indirect communication, which is circulated or posted online, and misrepresentation online. Cyberstalking cases – especially those across borders – are difficult to prosecute, as countries have different laws on stalking. But even those where both the victim and the perpetrator are in the same country are proving difficult for police and prosecutors to understand, as they play catch-up with tech-savvy perpetrators.

Many stalkers threaten their victims from nations without stalking laws. US-based internet service providers (ISPs) and companies such as Google, Yahoo! and Facebook, require a court order for information about stalkers to be served in the country of their headquarters. That can be costly and time-consuming. The Crown Prosecution Service in the UK has noted that such requests can mean delays of up to three months, compared to a real-world stalker who can be arrested within hours. ISPs often delete e-mail data after 30 days. If the victim has also deleted the distressing e-mail, the evidence may be gone for good. Other ISPs insist on notifying their customers (the perpetrators) that the police are investigating, giving them time to delete crucial evidence. Technical dodges give stalkers flexibility. Special software allows them to send untraceable e-mails from concealed addresses, and investigators say that they are unable to monitor instant messaging.

Stalking has always been a highly gendered crime. It is estimated that around 80—90% of stalkers are male and 80% of victims of physical stalking are female (although men may have been more reluctant to report crimes like these). More men experience cyberstalking than physical stalking, but women remain disproportionately affected both on and offline. Victims fall into three groups – most people are actually stalked by strangers, followed by acquaintances, with ex-intimates making up the last category.

The Fundamental Rights Agency carried out a survey of over 42,000 women across the European Union's 28 countries in 2012, only 11 of which have specific anti-stalking laws. It found that 18% of women had experienced stalking since the age of 15 and 5% had experienced it in the year running up to the survey – nine million in the EU within a period of 12 months. Across the EU, three quarters of women did not report the crime to the police – even in the most serious of cases. The agency concluded that the police needed to do more to publicise their work in stalking. They also felt that internet service providers needed to do more themselves to support stalking victims to report abuse, and address perpetrators' behaviour.

One woman, who took the law into her own hands instead of going directly to the police in Germany – where the reporting rate to the police of stalking cases is just 21%, was a sometime police officer herself. Ariane Friedrich, who was also a prominent Olympic high-jumper, was horrified to open her Facebook fan page, just months before the London Olympics, to find that a man had sent her a picture of his genitals. Friedrich did not click on the link. Instead she published his name and address on Facebook. The man confessed to having harassed her with an obscene message, but the action she took to defend herself created a public debate about how to combat stalking and cyberharassment in Germany. She was asked why she pursued a "vigilante" approach and was accused of using the internet to "pillory" the man.

Germany's strict laws around online privacy state that no one can post another person's personal information without their consent. Birgit Becker, a German cyber crime expert in the Frankfurt police force, believes that confidence in reporting stalking must increase, but she also acknowledges that the low conviction rate in Germany – just 2% in stalking cases – is unhelpful.

With victims often denied justice, it is not surprising that few have confidence in the legal system to protect them and take action themselves. The Electronic Communication Harassment Observation (ECHO) project, which reported the experiences of self-defined victims of cyberstalking in the UK, found that attacks violated all aspects of an individual's online presence. Dr Emma Short, who co-authored the study, found that the attacks affected all aspects of victims' health. Frequently, because of anonymity, the harasser was not identified, and the victim lived in anxiety and fear. A study from Australia suggests that many stalking victims display at least one symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder, whether or not they have been physically assaulted. Others show that victims become more fearful, distrustful of others, can develop physical illnesses and can even become suicidal. Many also suffer financial harm.

TROLLING OR STALKING?

Cyber-harassment and trolling – repetitive abuse on social media – has become a persistent problem across all platforms. Last summer the journalist Caroline Criado-Perez, who was campaigning to put Jane Austen's face on a bank note, became the target of vicious attacks on Twitter in the UK, including rape and death threats. A number of women who defended her were similarly hounded. Twitter was accused of being slow to respond. Following the threats, Twitter reformed its "report abuse" function, but the emotional damage to the victims had already been done. Two perpetrators later pleaded guilty to sending menacing messages and received jail sentences of 12 and eight weeks respectively.

Earlier last year, the Cambridge University classics professor Mary Beard also came under fire on Twitter and under social networking sites – the first time after appearing on the BBC in early 2013 and mildly defending the benefits of immigration. The next day, commenters on the now-closed Don't Start Me Off website, which encouraged anonymous posters to vent their wrath on targets chosen by the administrator, launched an attack on Beard. The trolls posted sexual and other taunts. Beard was soon defended – by supporters who included, she says, stand-up comics, who posted reams of Latin poetry on the site, but she was shaken.

Beard was targeted again during the Criado-Perez assault. Some comments were just nasty, she says, but others were more serious and were reported to the police, although they did not result in a formal complaint. Unlike others who were targeted, she found Twitter relatively responsive, but she did not want "some poor complete idiot to end up in court" and decided not to pursue the issue further – Beard went on to deliver a ground-breaking lecture, Oh Do Shut Up Dear, examining how the public voice of women has been silenced since classical times, in March 2014.

She has thought long and hard about those who targeted her and why.

"In some ways, social media has reinforced the access to a public voice, but then they do not get a response, so some people get angry and write themselves out of the public debate by tweeting threats like 'I want to rape you and I am outside your house', which is both scary and silly," she says. "It is important to note that this is trolling, not stalking. When the going got really rough for me, I searched for my name on Twitter and I would talk back to them and ask them not to do this and, at that point, I had more apologies than further threats."

However, Beard also feels that women and other users of social platforms do have to be resilient to some degree of disagreement. "We might want a user-friendly female culture but the world isn't like that. We have to be able to withstand some degree of resistance."

THE CYBER MOB

The Task Force on Cyber Hate is an increasingly influential international body, that brings government officials, industry representatives, law enforcement officials, academics and a small number of activists (among them figures from the Center for Democracy and Technology and the Anti Defamation League) together to discuss how best to challenge the worst excesses of online hate. It stemmed from groups opposed to online anti-Semitism but has widened its remit to include all online hate.

Police Superintendent Paul Giannasi, an expert in hate crime from the UK, serves on the task force: "When we first met I was surprised to find that key personnel from the social media operators had never been in the same room before and we had to introduce them to each other," Giannasi says. "They are competitors and not natural partners, but they are under the same pressures to protect the competing rights of free speech and protection from harm, and I believe their attitude has changed positively during the time of the group."

Giannasi wants to see the same attention to illegal online hate speech as has been applied to other forms of hate crime in the UK, where British police have pioneered a user-friendly online reporting system, True Vision, which allows victims to report hate crime online to the police. Facebook, for instance, which went public last year, has become more responsive to misogynist pages because Nationwide and Nissan threatened to remove advertising space – partly under pressure themselves from a coalition of influential women's groups. Twitter, too, which has also floated, has become more responsive to pressure.

Professor Danielle Citron, of the University of Maryland, has studied cyber crime, and serves on the Task Force on Cyber Hate. Her new book, Hate Crimes in Cyberspace, will be published by Harvard University Press this autumn. It is the first systematic account of the problem, and how to counter it. Professor Citron proposes practical and lawful ways in which to punish online harassment and also demonstrates the emotional, professional and financial damage incurred by victims.

She describes some attacks as rape fantasies – others as persistent reputation-ruining lies. Others have become known as "revenge porn" – usually men posting sexually explicit photographs or videos of their ex-partners, sometimes with names and addresses attached. This can, she notes, incite strangers to stalk their victims in turn, or create group cyber-mobs, whereby more than one person is involved in online harassment. It can, as she puts it, "become a team sport".

Sometimes online abuse has resulted in just what victims dread – real life rape and stalking. One woman was raped and seriously abused in Maryland in the US by a stranger in 2009, after her address was posted on Craigslist by an ex-boyfriend. And if dealing with a single attacker's "revenge porn" were not enough, harassing posts that make their way onto social media sites often feed on one another, turning lone instigators into cybermobs.

Citron does not see the internet as a Wild West, where those who venture online must endure assault in the name of free speech. She believes that we must use civil rights law, and legal protection, as well as social norms of decency and civility to stop it. She has found that around 60—70% of online harassment is targeted at women and much is sexualised and demeaning.

Although her work has documented online misogyny, she acknowledges that men also get targeted online (as well as lesbian, gay and transgender people, and those from minority ethnic groups). "Men are targeted and are either 'reduced' to being gay or are demeaned and threatened with rape. Then there was the well-known case of the writer, James Lasdun, who was cyberstalked for several years. The abuse was riddled with anti-Semitism and he was also falsely accused of having raped his stalker – so again you see the sexualised nature of the abuse, but it is turned on its head."

So what are the best strategies for countering online stalking and harassment? Citron does not believe that answering back, however tempting, is valuable, particularly if the attacker is sheltering behind the veil of anonymity. "Even if it is physically valuable, what is there to say? There is no meaningful counter-narrative – they get hit back even harder . . . self help is a risky proposition." In her view: "You don't fight mob justice with mob justice. We are not in Clint Eastwood land – or I hope we are not." Instead, she proposes an attack on many fronts to change the rules of engagement on the internet, including education, changing community norms and engagement with social media operators. On the latter front she is cautiously optimistic: "The intermediaries are fast becoming virtuous players in this. The commercial internet has only been around since 1995. I have seen enormous change in just six months."

HATE CRIME 2.0

Twitter in the UK, in 2013 and 2014, has become a febrile, angry place, with cyberharassment rife on many fronts. For example, one prominent transgender activist, who would prefer not to give her name, while praising most feminists says that most harassment they get online comes from a community known by them as "Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists". Some run a number of websites that "doxx" or publish the names, photographs and addresses of transgender people. This can place them at risk of offline physical attack and is an invitation to stalking by proxy, whether intended or not. One site weaves the details of transgender people, not convicted of any criminal offence, among the details of convicted sex offenders.

When it comes to disabled people and the internet, a small number of people have used social platforms as an online modern freak show. In February 2010, three executives for the internet service provider Google were convicted of violation of privacy laws in Italy. The case had been brought by a disability charity, which claimed that Google was culpable for not gaining the consent of all parties in a video before it was uploaded to Google Video.

The clip showed a young boy with autism being beaten, humiliated and insulted by a group of youths at school in Turin. It was, briefly, rated as the funniest video in Google Italia. In another incident, in Melbourne, at around the same time, a group of high school students assaulted a disabled girl, urinated on her, set her hair on fire, sexually assaulted her and then posted their exploits on YouTube.

Sue Marsh, who has been one of the leading voices of Spartacus, the online protest group leading the opposition to the British government's disability benefits cuts, says that online harassment has not been as hostile as she was expecting – and that engaging with opponents has, on the whole, been beneficial.

"I can see people living in a state of permanent upset on Twitter, but perhaps it isn't the place for them in that case. It is really best not to engage with trolls because they are just trying to get a rise and we just ignored it or replied tongue in cheek. Of course cyberstalking – the persistent and targeted abuse – is different, and we have also had that experience with our campaign. But even there, the way that the dislike was expressed online probably helped the campaign, although it was frightening at the time."

EU PROTECTION

There has been some real progress for the victims of cyberstalking, both in Europe and internationally. On August 1st, the Istanbul Convention became binding in the European countries which have ratified it, meaning that there is harmonisation of laws regarding violence against women across Europe – including stalking. The stalking harmonisation in the Convention has been drafted so that it is gender neutral to protect both men and women.

Johanna Nelles, head of the Violence against Women unit at the Council of Europe, says that the Convention is highly significant. "It introduces the offence of stalking across all countries that ratify the Convention and also stalkers can be given a restraining order." Such orders (called European Protection Orders in the Convention) have been used for stalkers in the British situation but are not standard across the rest of Europe.

Fourteen countries have ratified the treaty thus far (not the UK). It does not distinguish between on and offline stalking, Nelles says. "We have left it at a general level so that each state can develop its own legislation." But, she stresses, Article 62 places an obligation on states to increase co-operation across borders, including the enforcement of protection orders. This could boost the safety of stalking victims across Europe.

That the treaty came about at all is partly because of sustained campaigning on the part of two British charities led by survivors of stalking – Alexis Bowater, the chief executive of the Network for Surviving Stalking, and Ann Moulds of Action Scotland Against Stalking. Moulds, for her part, says that the directive restores the voice of the victim to the process and she has argued for countries to use Scottish stalking law as the European template. Crucially, Moulds also linked up with Victim Support Europe across the continent. "Systems on their own don't listen to or tolerate victims. This got us into Europe. At one point I was holding down three jobs so that my voice as a victim wasn't lost."

The work of survivors like Moulds and Bowater has been pioneering. Britain has led the way in assessing the risk of violence in stalking cases; prosecutors have issued guidance on how to handle cases. The UK has the only stalking helpline in the world and funds limited treatment for some stalkers, the only such programme in Europe (apart from one walk-in clinic in Berlin). A new high profile stalking service, Paladin, is now advocating for high-risk victims and offering bespoke training for professionals assessing the danger of perpetrators. Another step forward is Ramm's fledgling organisation in the US, the non-profit Alliance Against Cybercrime. Its first project, the Ramm Initiative, focuses on cyberstalking and attempts to tie it to cybercrime generally.

Currently, Europol's cybercrime unit does not even mention cyberstalking on its website. Ramm is calling for the Council of Europe's Convention on Cybercrime, to which the US is a signatory and which is the gold standard for tackling all forms of crime relating to the internet, to be amended so that it includes cyberstalking as a punishable offence. At the moment cybercrime units concentrate on terrorism, cybertheft and computer security. The financial and emotional cost of cyberstalking impacts individuals, rather than corporations or governments, so has not been a priority for governments. Time, victims argue, for a change.

Leandra Ramm lost one career and a decade of her life. A cyberstalker tried to destroy her. But she's now married, with a child on the way. "This happened for a reason," she says. "I'm not just going to forget about the other victims because I won my case.