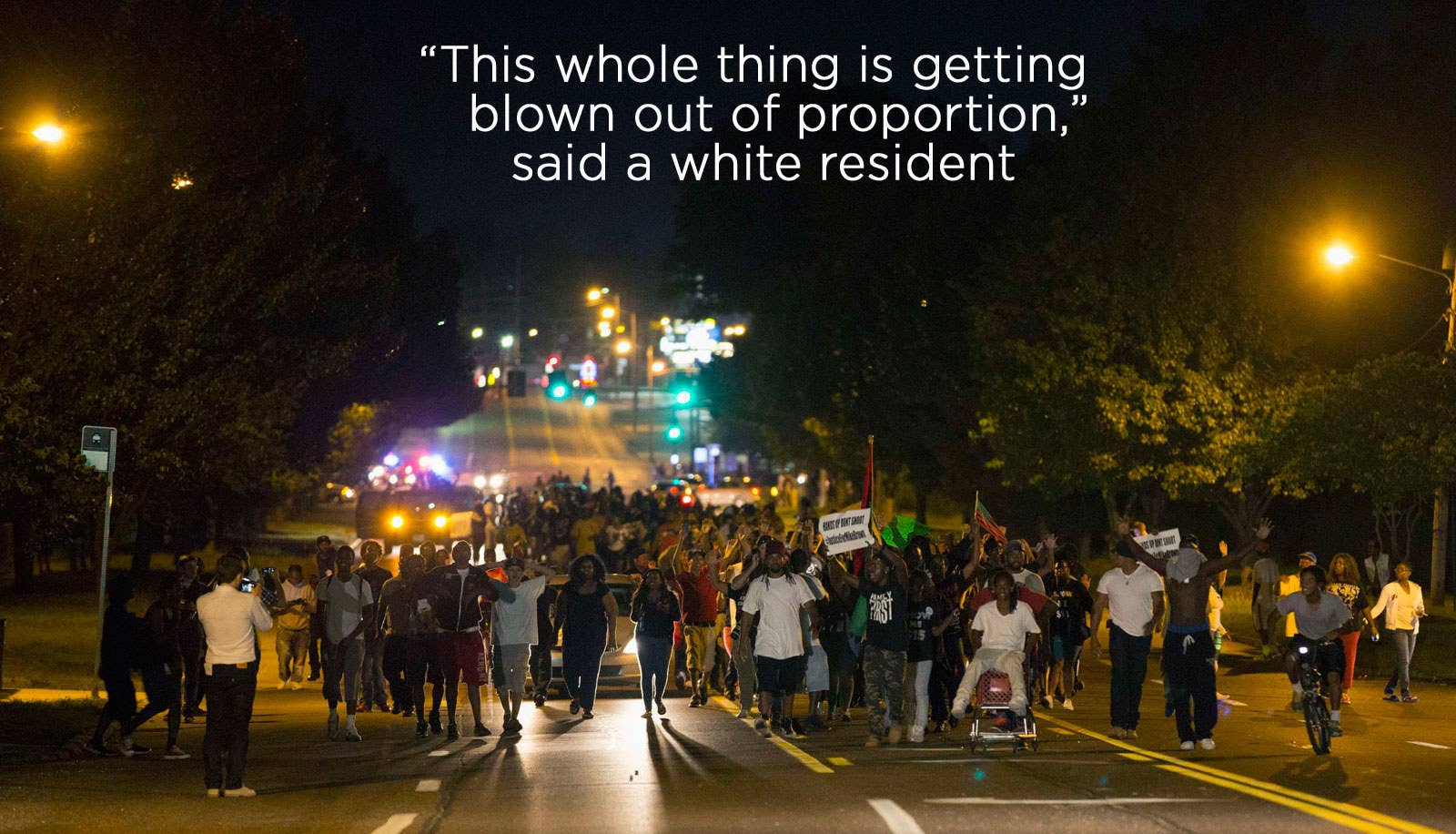

FERGUSON, Missouri — From his neatly manicured front yard, Peter Tries could hear sirens in the distance. But the armored vehicles bristling with officers wielding assault rifles, the large cable TV news trucks, and all the other scenes that flooded America from his hometown of Ferguson — none of that happened in his neighborhood. And he objects to the view of his hometown as a cauldron of racial tension.

“I think this whole thing is getting blown out of proportion,” said Tries, who is white and 35 years old. “There’s never been any kind of race thing here. It’s something I never even think about.”

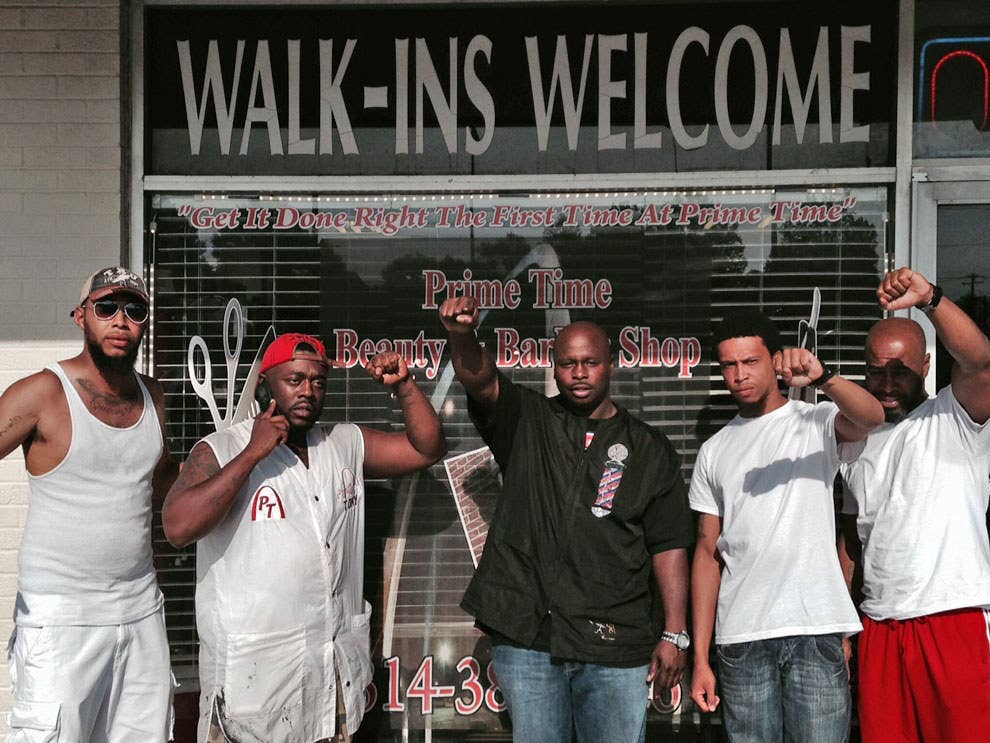

Over at the Prime Time Beauty & Barber Shop, a social hub in the black part of town, folks see it differently. “They treat us like criminals,” said barber Branden Turner, who’s worked at the shop for a few years. They described officers routinely waiting for customers to leave so they could give them traffic tickets, search for drugs, or ask them for identification so they could run a background check.

“Everyone knows the statistics,” said Turner, referring to the now well-known figures showing a disproportionate amount of traffic stops and arrests for blacks. “Ask anybody from the city,” he said, meaning St. Louis. “Don’t nobody come in from the city because they know this is one of the most racist places there is.”

In this city of about 21,000 people, the national spotlight has forced residents to grapple with dueling narratives of their relationship to each other and to their government. It’s a tale of two cities that happen to exist in one town: Ferguson. More largely, it’s a tale of two Americas, black and white, that seem to exist in totally different realities and have sharply divergent views on race.

Many black locals welcome the unflattering attention, hoping it might lead to change in a city where whites are only 29% of the population but five of the six city council members, six of the seven school board members, and — as repeated ad nauseam this week — 50 of the 53 police officers.

“We’re tired of being bullied,” said Jayson Ross, a 25-year-old native who has been a regular presence at the nightly protests.

Those demonstrations weren’t just a reaction to the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson. They were also a fiery response to years of grievances that were routinely ignored by most of Ferguson’s white residents and by its predominantly white government. It’s the same pent-up fury that sparked protests in small towns made infamous by previous race-related controversies that went national: Sanford, Fla.; Jena, La.; and Jasper, Texas, notable among them.

Regardless of the geographic region, the community response follows a predictable script: White residents almost always find themselves surprised by the simmering discontent of their black neighbors. And why wouldn’t they be? They usually live in a different part of town, no longer segregated by law but by history, custom, and sometimes policy. What’s more, the police and other arms of government treat them with respect. Many white residents don’t think there’s much racial discontent because they just don’t see it.

Ferguson sprouted to life in the mid-nineteenth century as a hub for freight and passenger rail traffic in a nominally Confederate state. After the Civil War, a small parcel of land, inside what is today Ferguson, was set aside for former slaves to build small cabins. The area was called “Little Africa,” according to Ferguson: A City and Its People, which was published by the Ferguson Historical Society in 1976.

In that book and a follow-up edition that focused on life in town after the 1920s, the black contributions to Ferguson receive only a few passing mentions: slaves freed by merciful plantation owners, a Baptist church founded by former slaves in 1880, and a school that opened for black students in 1885 — though high school-aged children were forced to travel nearly 20 miles because the local high school wouldn’t accept blacks.

Mostly, the books are a tribute to the prominent white families and business owners in town: the Schmidt Bros Confectionary on Church Street, Bindbeutel’s Market, Kienstra Coal and Feed Company, to name a few. Only three black people, none of them identified, none of them women, can be found on the pages of those books.

The town’s white majority didn’t begin to dwindle until the 1970s, when white residents fled St. Louis and its inner suburbs, including Ferguson. By 2000, blacks made up half of the city’s population, and whites had dropped to 44%. Those trends continued through the 2010 Census, which found that more than two-thirds of the city was black and that whites made up less than 30%.

“I grew up here, and it’s always been a very diverse community,” said James Knowles, mayor of Ferguson since 2011, who is white. “So for people to come out and say that there’s some long-standing anger or there’s a history of racial tension is absolutely ridiculous,” he said. “There’s not a black-white divide in Ferguson.”

The mayor and the rest of the local government epitomize the black struggle to have a voice. Ferguson has rarely had more than one black city council member at a time. In April, voters elected the first black school board member — but earlier in the year, the then all-white board had ousted the area’s first black superintendent.

“The power structure is run by pretty much all white people,” said Don Calloway, a former Missouri state representative who is black and whose district included part of Ferguson. “All of these black people are basically under white rule.”

But it’s Ferguson’s police department that has received the most scrutiny, in part because of its paltry number of black officers and documented racial disparities in traffic enforcement. Last year, Missouri’s attorney general found that blacks made up 86% of all traffic stops in Ferguson despite being roughly two-thirds of the driving population. That data also showed Ferguson police officers were twice as likely to search and arrest blacks during these stops as they were whites.

“It’s part of the overall system letting us know that there’s no love for black people here,” said Kerry Woods, who lives in nearby Jennings but came out for Wednesday’s protest. “It’s a good ole boys system.”

On the other side of town, along a street with only a handful of black homeowners, Don Chisholm empathized with the desire for justice in the investigation into Brown’s death but was pained by the racial tension surrounding the case.

“I think the race relationships have always been good here,” said Chisholm, who has lived in Ferguson since 1965. “There’s no strife between the races. And I think these protests are going to damage that.”

Chisholm then echoed a sentiment common among nearly a dozen white residents interviewed by BuzzFeed over the past few days: “I wonder, are these professional protesters or people who really live here in Ferguson?”

The protesters, Tries reasoned, “they aren’t Ferguson residents.”

To counter the image of Ferguson as a town beset with racial division, sisters Laura and Elizabeth Knight staged their own demonstration along North Florissant Road on Thursday. About a mile away from where Brown supporters were rallying outside of the city’s police station, they hoisted “I heart Ferg” signs at passing motorists.

“This isn’t directed at any person,” said Laura, a recent graduate of Knox College in Illinois who hopes to move back to Ferguson. “I just love my community, and I’m proud to come from here. We’ve seen a lot of things on TV, but we don’t see enough positive.”

“I think you can be angry at things going on in a place without being angry at the place you live,” Elizabeth said.

Mayor Knowles did acknowledge one division in his town: that between homeowners and renters. “We have a divide, unfortunately, between people who stay here and people who live here,” he said. “We’ve got to find a way to integrate those people into the fold.”

Brown was fatally shot at a large apartment complex, Canfield Green, just off West Florissant Avenue. Brown was on his way to visit his grandmother, who lives in an apartment there.

Back at Prime Time, barber Toriano Johnson and others remembered Brown — a regular customer — as a lumbering teenager who didn’t say much. But at 6-foot-4, and built like an offensive lineman, Brown was hard to miss when he came through the doors of the shop.

What did Johnson think would come of Brown’s death? “I think it’s going to lead to the dismantling of the police department and the city government,” Johnson said. “Then we can start over. That’s what’s got to happen for us to all come together.”