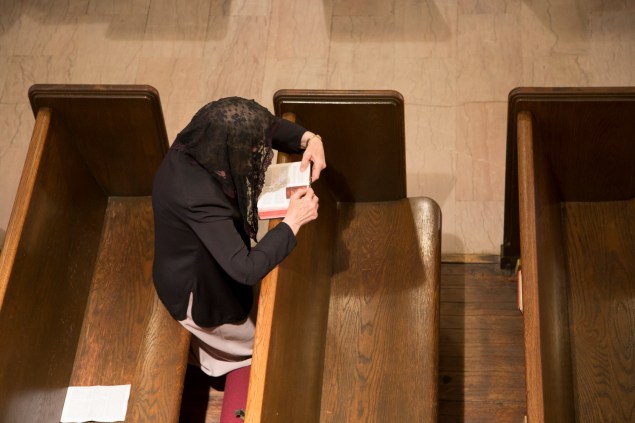

Down the street from the lights and sounds of Times Square stands the oldest building in the Garment District, the Church of the Holy Innocents. Over the decades its neighborhood has evolved into the tangle of chain stores and litter that it is today while the almost 150-year-old church has remained mostly the same since the day it was built. Step inside and the din is somehow lost, replaced by the last quiet, peaceful haven for New York’s traditional Catholics.

Yet what makes Holy Innocents truly unique is that it is the last Catholic church in the city to offer the Mass in Latin. The Latin, or Tridentine, Mass has been performed since the 6th century, and this rare service seems to have the effect of transporting one backwards through time. In the same way that the Mass is a testament to the past, the building itself is a landmark in New York history: giving last rites to those in the plane that crashed into the Empire State Building during WWII, baptizing Nobel laureate Eugene O’Neill, officiating the marriage of performer Jimmy Durante, and overseeing the conversion of poet Joyce Kilmer.

Nowadays, however, the very thing that makes this place so extraordinary is also the thing putting it in danger. Despite the artistic, cultural and financial strengths of Holy Innocents, the church was recommended for closure in April as part of New York’s “Making All Things New” initiative (a title one parishioner called “Orwellian”) to consolidate superfluous church spaces.

The reasons cited for the potential closure were that the church is not considered by the advisory board to be “an active, vibrant community of faith,” according to a letter from Timothy Michael Cardinal Dolan, Archbishop of New York, sent in response to concerned parishioner and Frick Institute employee Valeria Kondratiev. “A parish church is meant to be a center of worship and not a museum,” he went on to say, addressing her concerns for the enormous, exquisite and priceless Constantino Brumidi mural affixed above the altar that would, in her opinion, most likely be unsalvageable if the church were closed.

This comes right on the tails of an immense $700,000 renovation project undergone just last year with most of the money going to restore the Brumidi mural. The project was paid for in major part by donations from parishioners and partly overseen by the same Archdiocese that may have known far in advance of the church’s potential for consolidation. “Some people … gave until it hurt,” parishioner Ron Mirro said. “It’s just very upsetting.”

The puzzling thing about the cardinal’s claims of a lack of vibrancy in the community, however, is that Holy Innocents seems to have exploded in popularity since starting daily Latin Masses in 2010. Total Sunday Mass attendance is now 250-275, nearly triple the average attendance of 100 people in 2009. The church is nearing 75 percent of its ordinary seating capacity of 350-400. In addition, it is currently completely debt free with donations on track to double in the current fiscal year from the last.

Explanations for an inexplicable closure range. Some, like Mark Froeba, volunteer co-coordinator of the Holy Innocents Latin Mass, believe it’s an issue of misinformation and miscommunication. Mr. Froeba told the Observer that priests who were trained after the Second Vatican Council grew to harbor an animosity for the Latin Mass and the old, problematic ways of the church that it came to represent for them.

“[To] a certain generation of priests, this is … the culture of the church they rejected in their youth … They’d come to believe that it was the source of all the problems in the church: it was paternalistic, it was rubrical and not spiritual … all these sorts of condemnations that they came to believe in a heartfelt way, for them to now see it coming back is shocking to them,” Mr. Froeba said. “They’re hostile to something they fought 50 years ago that doesn’t really exist anymore and this is a whole new thing, very much a product of the things that they fought for.”

Others claim that the reason for closure lies in monetary gain from its prime real estate location—a five minute walk from all subway lines. Edward Hawkins was for years the leader of Holy Innocents’ chapter of the community service and fundraising philanthropic group, the Traditional Knights of Columbus. “I’m worried that it’s being devalued and blinded by the real estate. That’s what’s really happening,” Mr. Hawkins said. “If they take this away from us … we’re never gonna get this community back. The people should be valued and they are not; it’s real estate that’s valued.”

Unfortunately, Holy Innocents has little recourse to save itself. “As Catholics we are called to be obedient to our clergy and that’s what we accept about our faith,” said Con O’Shea-Creal, a regular commuter to the church from Queens. He and his wife Paige were recently married at Holy Innocents. The young couple agreed that they trusted in the Archdiocese’s final decision but that sometimes it can be difficult to do so.

This attitude is reflected in many of the parishioners of Holy Innocents. They are left with a feeling of helplessness and fear, making change.org petitions and writing pleading letters to the cardinal, but incapable of doing much else besides their daily Mass, to which they have added a prayer for the health and heart of Cardinal Dolan to spare their church.

The Latin, or Tridentine Mass, was abandoned in favor of the preferred New Mass, or Novus Ordo, after the second Vatican Council in 1970. The Council sought to make worship services less alien to modern worshipers and bring in new Catholics by making the church more accessible. They hoped to bring about more enthusiasm and community involvement.

Holy Innocents was built for the Latin Mass in the mid-19th century, but the Tridentine fell out of favor for about a generation after the Second Vatican Council ruled the New Mass as the preferred form. This New Mass became, with few exceptions, the only form of the Mass allowed until Pope Benedict XVI gave his permission in 2007 for wider use of the Latin Mass. In 2008, the Latin form came back to Holy Innocents, and it has contributed to the church’s current flourish. Founded in 1866, the parish will celebrate its 150th anniversary in two years—if it survives that long.

Parishioners are made up of a diverse cross-section of races, ethnicities, and, surprisingly, ages. It is a common misconception that traditional Catholics are predominately elderly, but the Latin Mass is seemingly burgeoning in popularity among young Catholics, such as Eric Genovese, who recently turned 17. “Young people are looking for a bigger sense in tradition … and I guess they find that more… in the Latin Mass,” he said.

Mr. Froeba had some insight on why this might be. “Authenticity [is] the zeitgeist of our time. People don’t want the copy, they want the original,” he told the Observer. “For some people, especially young people, that’s what [the Latin Mass] represents. It’s something that has a history that stretches not just a few decades but centuries, even millennia.”

The two main issues that Holy Innocents rallies for are the protection of the Latin Mass and, with its Shrine of the Unborn, the pro-life movement. The latter concern is a testament to the widespread question of whether the Latin Mass is inextricable from the more problematic elements of the traditional church that many believe should become more socially liberal including acceptance of female priests, gay marriage, transsexuality, and many other issues, abortion included.

Mr. Froeba maintains that the Mass, Tridentine or Novus Ordo, “should reflect whatever the church teaches and whatever the church teaches should be embodied in the Mass.” Social change has happened before in the church, he said, and it may well happen again. Mr. Froeba cites church stances on usury, the death penalty and slavery while going on to mention the Archdiocese’s recent support for the Church of St. Francis Xavier in Chelsea, a parish that caters to the LGBTQ community. “There’s precedent for development of doctrine,” he said.

Judge Andrew P. Napolitano debates such issues on television most of his days as the Senior Judicial Analyst for Fox News Channel, but many of his nights are spent at Holy Innocents. “The cardinal … [is] a terrific human being … He has a very, very big heart. I am confident that in that very big heart of his, there’s a place for [Holy Innocents],” he said. “One of the church’s truisms is ‘sacred then means sacred now,’ ” he told the Observer. “The church teaches that if something was sacred, it was always sacred and it always will be sacred. Well, this Tridentine Mass was sacred for 1,400 years. It is sacred still.”

A reason stated for the creation of the phasing out of the Latin Mass was a desire to unify the church. The belief was that doing the mass in the vernacular would make it more approachable and more appealing to Catholics as attendance numbers continued to dwindle on the whole. This sentiment is not shared by many members of Holy Innocents, however.

“We pray the same prayers that have been prayed since time immemorial,” regular parishioner Adam Fera said. “When we sing hymns it not only unites us with Catholics throughout the world who are singing these hymns, but generations of Catholics before us … it’s a unifying force.”

The cardinal’s final decision on the status of the closure will be revealed sometime in September.