When Labor Day Meant Something

Remembering the radical past of a day now devoted to picnics and back-to-school sales

Labor Day online specials at Walmart this year “celebrate hard work with big savings.” For brick-and-mortar shoppers near my home in Chicago, several Walmart stores are open all 24 hours of Labor Day. Remember, this is a company so famously anti-union that it shut down a Canadian store rather than countenance the union its workers had just voted in. The fact that Walmart “celebrates” Labor Day should draw laughter, derision, or at least a few eye-rolls.

But it doesn’t—or at least not many. Somewhere along the line, Labor Day lost its meaning. Today the holiday stands for little more than the end of summer and the start of school, weekend-long sales, and maybe a barbecue or parade. It is no longer political. Many politicians and commentators do their best to avoid any mention of organized labor when observing the holiday, maybe giving an obligatory nod to that abstract entity, “the American Worker.”

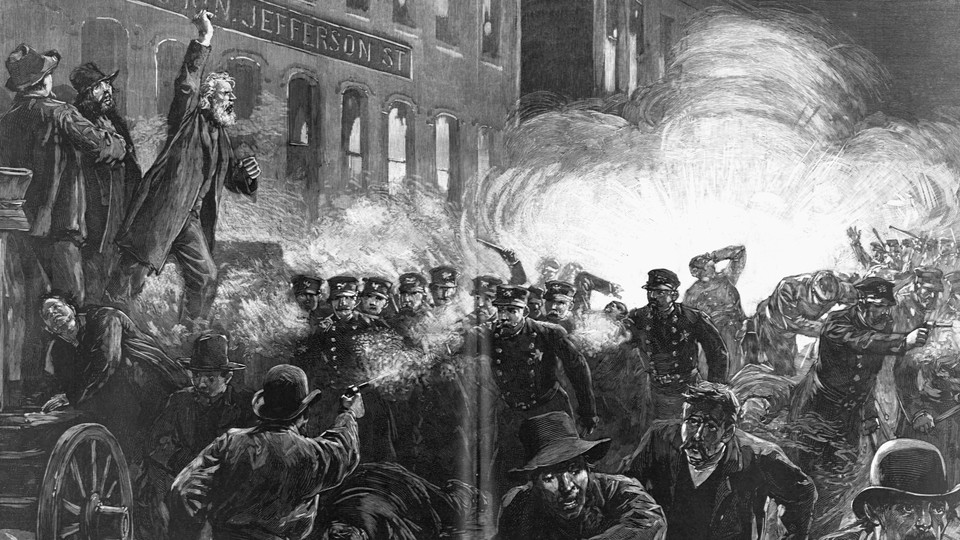

Labor Day, though, was meant to honor not just the individual worker, but what workers accomplish together through activism and organizing. Indeed, Labor Day in the 1880s, its first decade, was in many cities more like a general strike—often with the waving red flag of socialism and radical speakers critiquing capitalism—than a leisurely day off. So to really talk about this holiday, we have to talk about those-which-must-not-be-named: unions and the labor movement.

The labor movement fought for fair wages and to improve working conditions, as is well known, but it was its political efforts that did nothing less than transform American society. Organized labor was critical in the fight against child labor and for the eight-hour workday and the New Deal, which gave us Social Security and unemployment insurance. Union workers sacrificed in America’s historic production effort in World War II and pushed for Great Society legislation in the 1960s. Michael Patrick, a former local Machinists president from Galesburg, Illinois, where I’ve done research, cites his union’s support for Medicare and the Civil Rights Act, now celebrating its 50th anniversary, as among his local’s proudest moments.

These were victories that went well beyond the bread-and-butter issues of union members. They were shared achievements worthy of a national holiday for all. As Samuel Gompers, the founder of the American Federation of Labor, wrote in the New York Times in 1910, Labor Day “glorifies no armed conflicts or battles of man’s prowess over man… no martial glory or warlike pomp signals Labor Day.” Rather, “Of all the days celebrated for one cause or another, there is not one which stands so conspicuously for social advancement of the common people as the first Monday in September.”

Those shared victories came at a cost. Agitation for anti-trust legislation, shorter workdays and workweeks, and the right to organize was often portrayed as un-American and violently repressed. In 1914, John Kirby, president of the National Association of Manufacturers, called the trade union movement, “an un-American, illegal, and infamous conspiracy.” Anti-labor employers fought against what they saw as incipient communism with strikebreaking, blacklisting, vigilante violence, and by enlisting government force to their side. During the Red Scare of 1919-1921, many states passed blanket sedition laws against radical speech and banned the flying of the red flag. The fiery but pragmatic president of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis, spoke to the overwhelming patriotism of union men and women when he said to a Senate Committee in 1933, “American labor stand[s] between the rapacity of the robber barons of industry of America and the lustful rage of the communists, who would lay waste to our traditions and our institutions with fire and sword.”

Labor Day began not as a national holiday but in the streets, when, on September 5, 1882, thousands of bricklayers, printers, blacksmiths, railroad men, cigar makers, and others took a day off and marched in New York City. “Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Rest, Eight Hours for What We Will” read one sign. “Labor creates all wealth,” read another. A placard in the following year’s parade read, “We must Crush the Monopolies Lest they Crush Us.” The movement for the holiday grew city by city and eventually the state and federal authorities made it official.

The national holiday emerged 12 years later in the face of a federal crackdown on labor. In 1894, at the behest of railroad companies and industrialists, President Grover Cleveland deployed more than 10,000 U.S. Army troops to break the Pullman strike in Chicago—the first truly nationwide strike, which involved more than 150,000 workers from coast to coast. Protesters were jailed, injured, and killed. Amid the turmoil that summer, and as an olive branch, Cleveland signed legislation to make Labor Day a national holiday.

Eugene Debs, the leader of the Pullman strike, dismissed the corporate paternalism of industrialist George Pullman, who sought to take care of “our poor workingmen.” The real issue, Debs said, was “What can we do for ourselves?” This—the labor movement's foundational values of self-determination and self-reliance—is what makes Labor Day a quintessentially American celebration.

Perhaps the main reason Labor Day’s meaning has been lost amid picnics and holiday sales is the decline of unions. Union membership across the country has shrunk to less than one in eight (35.3 percent among public-sector workers and just 6.7 percent among private-sector workers in 2013) from nearly one in four throughout the 1970s. As membership declined, so did public support. According to a just-released Gallup tracking poll, a slim majority of Americans approve of labor unions—down from as high as three out of four in the booming postwar years.

In the global, post-industrial era, industrial unions have less clout, and public-sector unions face well-resourced attacks from the right. In some cases, unions have left themselves open to criticism by retreating to the bread-and-butter concerns of its membership like wages and benefits, and by not embracing change, continuous reform and accountability, and an expansive vision of shared progress. Important new campaigns, though, are underway in retail stores like Walmart, in the tobacco fields and slaughterhouses where immigrants toil, and in charter schools where idealistic young teachers soon enough realize that they need a collective voice in the workplace to be treated and paid like professionals.

Shoppers this weekend could hardly be blamed for going to Walmart for the latest feather-light flatscreen television from China or Mexico—I’ll admit I’m dazzled by the low prices and pixel counts too. Or, better, people could go to Costco, where workers make about twice the Walmart wage, and don’t have to rely on federal benefits like food stamps and Medicaid (which, according to Americans for Tax Fairness, cost taxpayers $6.2 billion a year). In addition, Costco lets its workers unionize while Walmart instructs managers to report union activity or grumblings about wages to the company’s “Labor Relations Hotline.”

Holiday shoppers will have to wait until Tuesday, though, because Costco is closed on Labor Day. Its workers are where they should be—at the family barbecue or the parade, celebrating our national holiday.