If you want a symbol of Britain’s benefit system, Jaki would be it. The 36-year-old spent her 20s in Essex grafting – taking on any job to provide for her four children, even shelf-stacking for 60 hours a week. By 25, she started to get sick – the joint condition Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and the constant pain of fibromyalgia, on top of epilepsy – until she could barely walk.

Watching her life change was hard. “It’s like a grieving process for the person you could have been,” she says. But it was the welfare state that helped her get by: when she started to need a mobility scooter, the council adapted her two-bed bungalow – a wet room so she could wash, with lowered kitchen surfaces to help her cook – while disability benefits meant she could pay the bills for her and the kids when she had to give up work.

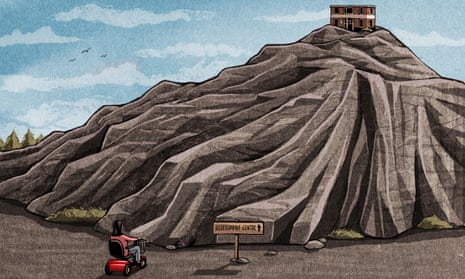

Then, exactly a year ago this month, Jaki was summoned to Colchester for “reassessment” – a two-hour round trip from her home in her scooter, to prove she was still disabled enough to keep her benefits. When she got there, she found herself staring up at the building: the entrance had a 5in step and no ramp. The slightest jolt in her scooter means pain for Jaki; each bump of the road shoots a spike up her spine. Besides, her scooter engine won’t lift her up the step – even if she holds her breath and rams it, the wheels just spin futilely.

A film-maker looking to document this decade’s punitive “welfare reform” might reject such an image as lacking subtly: a person with disabilities literally blocked from her benefits because the test centre isn’t accessible for wheelchairs.

And yet, for Jaki, it’s all too real. Forced to go home, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) told her she’d have to go to another assessment centre, this time miles away in Chelmsford – easy to get to if you’re healthy but if you can’t walk or drive, an ordeal. It’s an hour in a scooter to the train station, one change, and then another trek across town to the benefit centre, Jaki explains. “My scooter battery would run out by the time I got there.”

Q&ATell us: have you recently gone through a similar situation?

Show

Have you been sent to an inaccessible benefit centre or experienced something similar you would like to discuss with our journalists?

You can share your experiences by filling in this encrypted form – anonymously if you wish. Your responses will only be seen by the Guardian and we’ll feature some of your responses in our reporting. You can read terms of service here.

Unable to physically get to either assessment building, Jaki was promptly found fit for work “in her absence”. “Logic that Kafka would be proud of,” she sighs. That was August 2017. She hasn’t had a penny of her disability benefits since.

Look through piles of Jaki’s paperwork as she begs for help and it’s like reading a cruel game: the DWP ask her why she’s failed to attend her assessment, and in ink she writes, in block capitals: “I keep telling you … because I can’t get in the building.”

That our disability benefit system is broken is now beyond doubt. A government committee finds assessors so incompetent they ask a claimant with Down’s syndrome when they “caught” it. Whistleblowers leak that private companies are offering £50 “incentives” to assessors to squeeze extra tests into their day, while local papers run yet more stories of people being found “fit for work” just before they die.

But what’s happening to Jaki is perhaps the ultimate sign of a warped social security system: disabled people refused benefits because their disability means they can’t physically get to their assessment.

Jaki’s is not an isolated incident. In 2016, research by the charity Muscular Dystrophy UK into personal independence payments (PIP) found that two in five people with disabilities were being sent to an assessment centre that wasn’t accessible. I’ve since become aware of evidence that this has continued over the last two years for both of the government’s flagship disability benefits.

A wheelchair user in East Sussex who contacted me was sent to a centre that had only one assessment room on the ground floor; because there were “too many wheelchairs”, all but one person was sent home. A deaf man in Southend-on-Sea told me he had been sent to an assessment building where the only entry was through an intercom. When he eventually got inside, a booking error meant the interpreter left before the assessment was over.

A friend of Jaki’s, Ali, who uses a wheelchair, was also told to attend her assessment at either Colchester or Chelmsford benefit centre this year – and promptly found “fit for work” when she couldn’t get into the building. The 48-year-old had her benefits reinstated only when she repeatedly asked her local MP to intervene. Ali’s petitioning the minister for disabled people to make the test centre accessible, and is unflinching about what’s going on: “This is deliberate. They know they’re inaccessible appointments. They know we can’t access the building.”

I asked the DWP if it knew how many centres being used by them for disability benefit assessments aren’t fully accessible for disabled people, and the department had no comment. I asked the DWP whether there had at least been any improvement since the 2016 research and it had no comment.

Instead, the department said it is committed to ensuring “everyone gets a fair assessment”, adding that all their centres meet “legal accessibility requirements” and that disabled people can arrange to meet at more accessible sites nearby or ask for a home visit. But ask Jaki and the reality may as well be a parallel universe. A home assessment is like gold dust, and isn’t considered without a GP letter; at £25, without her benefits, Jaki couldn’t afford one. As she got more desperate, she asked the DWP to agree to do her assessment in multiple locations; a different test centre, the local jobcentre, and even the Colchester centre’s car park. She was refused each time.

For almost a year, she has had only her personal independence payments to live off – barely £300 a month – and the bills are lining up. Debt collection letters flood through the door; Jaki owes £800 to the water company alone. She’s lost five stone since her benefits were stopped. The three vouchers she’s eligible for from her local food bank were used up “long ago”, she says. She is so malnourished that she has developed mild scurvy. Parts of her teeth have broken off because her gums are so weak.

Six weeks ago, Jaki attempted suicide. It was her son’s 16th birthday and she couldn’t afford to buy him a present. “When they stop your money for a year …” she pauses, quietly. “You start to feel like you’re not really worth anything.”

When a government is using inaccessible test centres for disability benefits, this isn’t merely about a few steps – it’s something bigger. It embodies a system that routinely withholds money from disabled people who are entitled to it, and an attitude of contempt towards benefit claimants that says someone like Jaki can be left to rot with barely any fuss.

Jaki tells me bailiffs recently came to the bungalow to collect on her debts. They left because there weren’t enough possessions to take. “At that point, you don’t know whether to laugh or cry,” she says. The simplest, commonsense intervention from the government could stop all this in a heartbeat: a pledge to ensure no disability benefit is assessed in a building that disabled people can’t access easily. In the meantime, Jaki and others don’t stand a chance.

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org. You can contact the mental health charity Mind by calling 0300 123 3393 or visiting mind.org.uk. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org.