He is the poster boy of chess, a Nordic prodigy who became world No 1 while still a teenager and has since been rated the strongest player of all time. But Magnus Carlsen is locked in an escalating dispute with the game's governing body, Fide, over a world title match due to take place in November. At worst, the 23-year-old Norwegian world champion could be stripped of his crown this weekend.

At face value, the dispute involves prosaic concerns such as prize money, timings and contracts. But matters have been complicated by the mooted venue – Russia's Sochi Olympic site – and the fact that a Carlsen default would open the way for a Russian-based player to stand in and challenge for the title.

Carlsen won the championship last year by defeating the Indian veteran Vishy Anand, who then qualified for a rematch. There were no bidders to host the $2m (£1.2m) 12-game series, scheduled to start on 7 November, until Russia offered to host it at the Olympic village in Sochi.

Fide has told Carlsen to agree to the arrangements by Sunday. His manager, Espen Agdestein, asked for a delay in the match until spring 2015, citing concerns about the venue and financial arrangements. He said Carlsen could not make a proper decision until the end of a US tournament in St Louis that runs until 7 September. "It's critical for Magnus to focus on this tournament," Agdestein said.

But Fide's newly reinstalled president, the Russian tycoon Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, refused any delay and said that under match rules, the Russian Sergey Karjakin, 24, runner-up to Anand in the candidates qualifier, would be the substitute.

Karjakin is originally from Crimea and once played for Ukraine. But he is an ethnic Russian and in 2009 moved to Moscow. Last month he appeared in a Vladimir Putin T-shirt to support Ilyumzhinov against Garry Kasparov in the Fide election campaign.

Fide has close links to Russia, which has hosted several events. Karjakin's sudden opportunity will appeal to Moscow officials who in Soviet times regarded the world crown as their private fief. From 1948 until the breakup of the Soviet Union, all world champions bar Bobby Fischer were from the USSR.

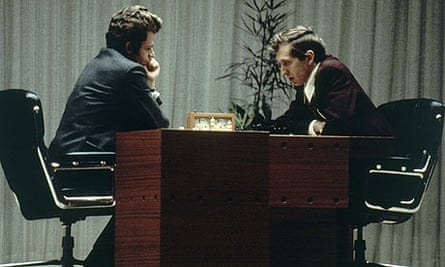

Fide's refusal to postpone the match has echoes of Reykjavik 1972, when Fischer failed to appear at the start against Boris Spassky and only escaped default because Fide bent the rules while Spassky defied Moscow's orders to return home. In 1975, Fischer lost his title without play against Anatoly Karpov after Fide refused to change the match rules. In 1993, Kasparov and Nigel Short broke from Fide and organised their match in the hope of a higher prize fund. The resulting schism lasted until 2006, when the championship was reunified.

Carlsen's reluctance to sign the contract is based on the diminished match budget – $1m less than Chennai in India provided in 2013. He is also said to be unhappy with the Olympic village venue, which many reports state has become a ghost site, and the lack of clarity about who is putting up the money.

If Carlsen does default, many will still regard him as the true champion. He crushed Anand last year and is ranked No 1 by a wide margin, while Karjakin is only No 7. Carlsen might arrange a match with the No 2, Levon Aronian, and there could be a high-profile series against Hikaru Nakamura, the US No 1 and world No 6, financed by the St Louis billionaire and chess benefactor Rex Sinquefield.

The reality is, though, that a Carlsen default could be a lose-lose situation for both the Norwegian and Fide. The global body needs the No 1 as champion. A schism would ruin Ilyumzhinov's reputation as a fixer who ensures scheduled events happen.

Carlsen also could face a fan backlash if he refuses to play, since Fide's regulations and deadlines have been known for many months. Being recognised by an established global body as an official champion helps his career. Long term, he would have problems in arranging his own title matches, as Kasparov found out during the previous schism. A compromise may yet be found. But the fractures in world chess are once again there for all to see.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion