These Stunning Images Capture the Unseen Beauty of Booze

Drink to the magic of polarized light microscopy

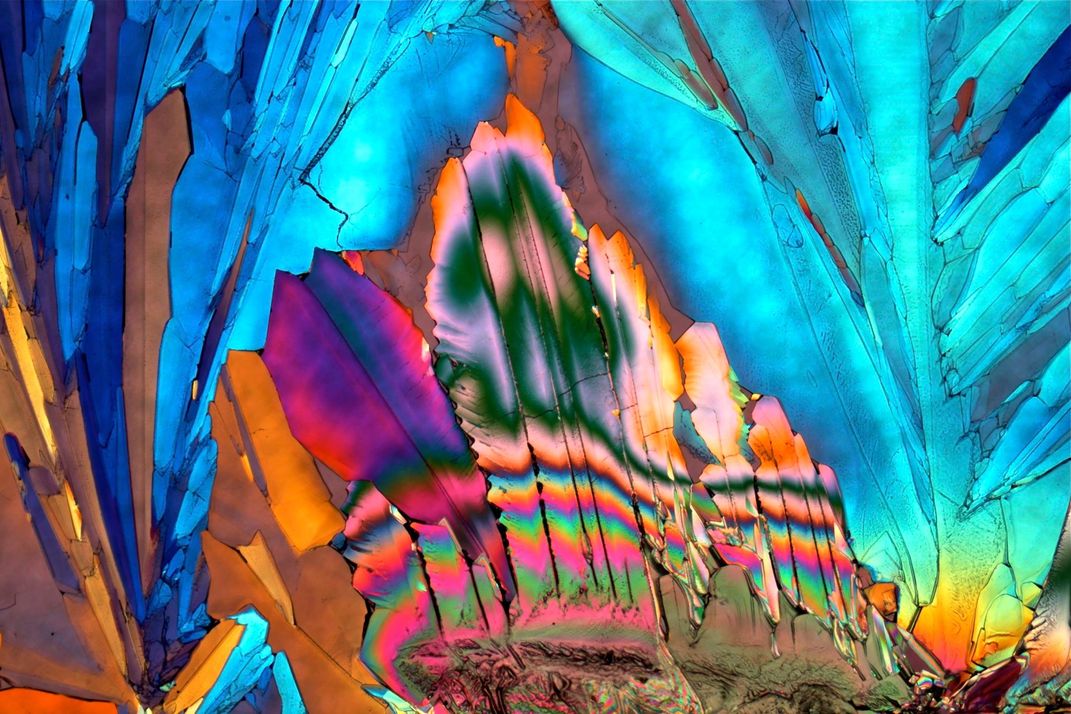

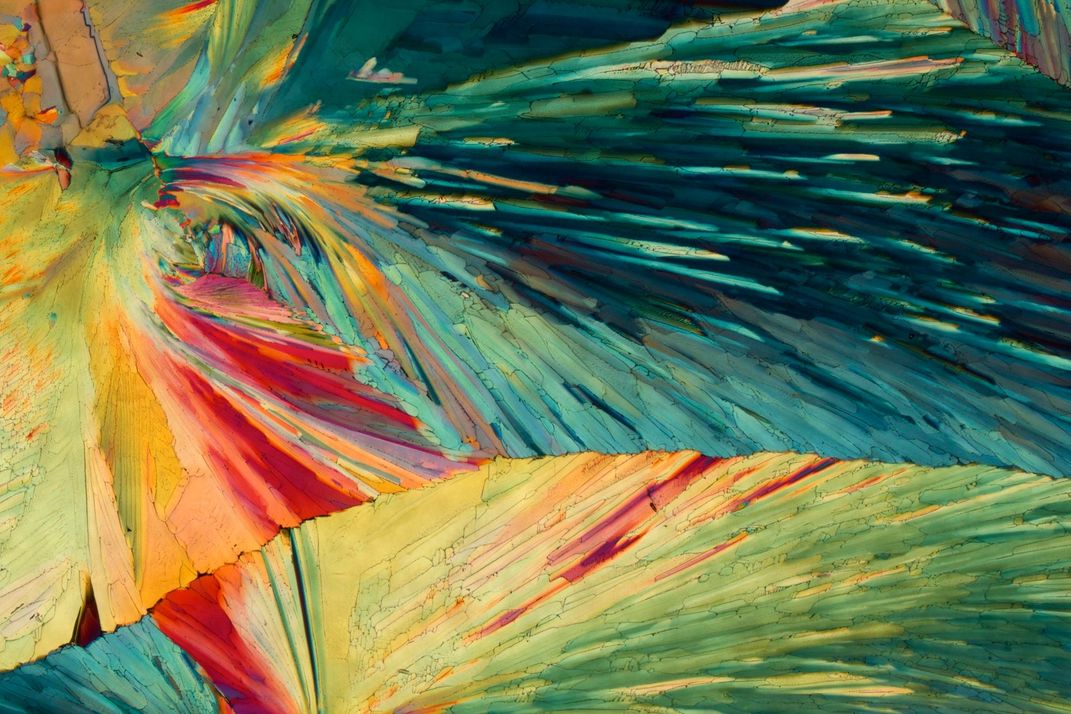

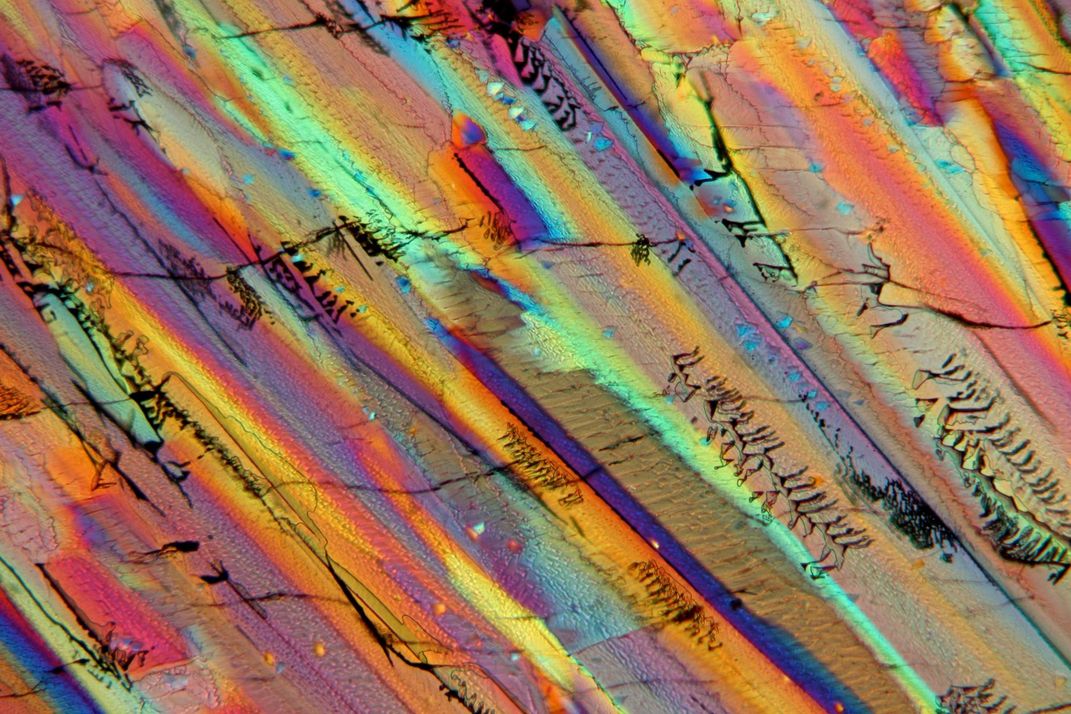

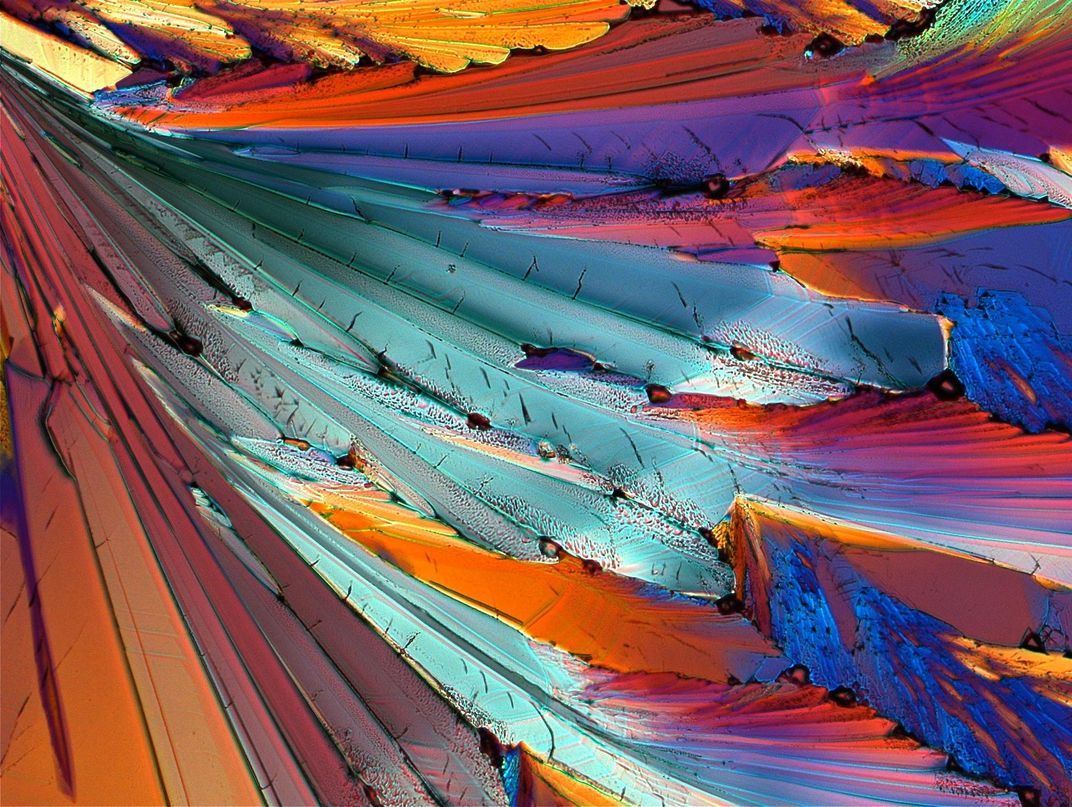

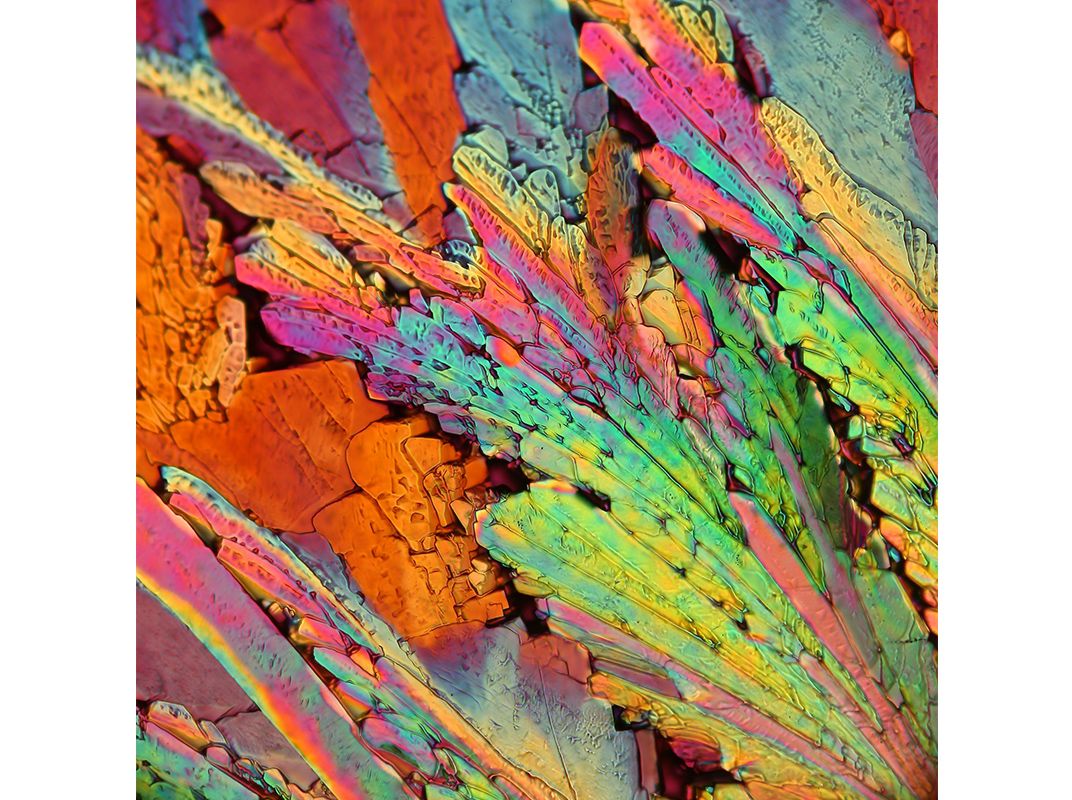

Consider the alcoholic beverage: It has a pleasing feel in the hand, a shimmering visual appeal, not to mention plenty of boozy deliciousness for your taste buds. But look closer and you'll see something just as extraordinary—microscopic crystals that form as that delicious drink dries out. As Stephanie Pappas reports for LiveScience, Italian geologist Bernardo Cesare has learned how to photograph those elusively beautiful crystals, and the result is nothing short of stunning.

Cesare, who is a professor of petrology, a field concerned with the origin and composition of rocks, at Padua University's Department of Geosciences, has long turned his camera toward rocks. He uses a photomicroscope—a camera mounted on a microscope—to look at the morphology, or form, of rocks in his day job. So it makes sense that he'd eventually turn his lens toward another kind of rock: crystals created by alcoholic beverages, such as Campari and Aperol.

Drawing inspiration from the photography of Michael W. Davidson, who specialized in taking snapshots of beverages using polarized light, Cesare began to study crystallized cocktails. It's not easy: He tells Pappas that the delicate crystals can take over a month to form. While the rocks that Cesare photographs can be sliced to half the thickness of a human hair, that's harder to achieve with drops of alcohol. The crystalline drops are placed on a glass slide and photographed with the help of polarized light.

Fields of non-polarized light—say, light from the sun—vibrate in a multitude of directions. Polarized light, however, is more controlled. Filters convert the random waves and force them to vibrate in the same plane. When trained on crystals, like the ones Cesare photographs, the polarized light makes an otherwise clear-looking plane into vivid rainbow of colors.

As Cesare said in a 2014 interview with National Geographic, he can achieve gorgeous, colorful photographs of dull-seeming rocks (or, in this case, booze crystals) without Photoshop. "When I find the right rock," he said, "I let her display her beautiful colors...by playing with polarizers." You may be used to your booze on the rocks, but perhaps the next time you take a sip you'll be reminded that your drink has plenty of aesthetic potential.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)