In 1956, the abstract painter Michael Canney, recently made a curator at the Newlyn Art Gallery in Cornwall, was surprised to see a diminutive figure pull up in a pony and trap. This in itself was unusual; even more so was that the figure was dressed as a jockey. It came inside and, Canney recalled, "strode around in a rather alarming manner, tapping its leg with a riding crop". Then Marlow Moss – for it was she – climbed into her trap and trotted back to the nearby fishing village of Lamorna, where she had lived since 1940.

If Moss's name is not known to you, then you are in good company. When a show of her work opens at Tate Britain next month, it is a fair bet that even those with a professional interest in modern British art will not have heard of her. For this, Canney, who died in 1999, blamed Moss herself.

Despite living in what was, in the 1950s, the crucible of English modernism, Moss, he said, kept herself "aloof". A stone's throw from St Ives, she had nothing to do with the artists there, even though most were abstractionists like her and, in the case of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, fellow members of the Paris group Abstraction-Création.

Although Moss had been the most devoted follower and friend of the Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian, St Ives knew nothing of her work. The cloud of forgetting that engulfed her was, Canney suggested, at least in part of her own making.

That cloud has only grown more dense. The display at Tate Britain will be the last in a tour of Moss's work that has taken in Tate St Ives, the Leeds Art Gallery and the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings. In spite of this, not a single review has appeared in a national newspaper, and little anywhere else. As the show's curator, Lucy Howarth, ruefully notes, the main effect of Moss's exposure so far has been to alert the Dutch museum that lent two works to the first show to the fact that they owned Mosses at all. As a result, the paintings are now hanging on the museum's walls for the first time in half a century, and will not be shown at the Tate. So complete has been the forgetting of Marlow Moss that when some of her work was shown at St Ives in 1997, the critic Tom Lubbock suggested that she had been made up. He was only half-joking.

Critics tend to flinch at the words "forgotten artist", the most common cause of their forgetting being that their work is rubbish. This is so clearly not so in the case of Moss that her eclipse seems scarcely believable.

Marlow, née Marjorie, Moss was born in London in 1889 and died in Cornwall in 1958. In the intervening 69 years, she changed herself utterly. The child of prosperous Jewish parents, she took herself off to the Slade, disappearing to Cornwall after a nervous breakdown. When she returned, it was as the crop-haired, jockey-clad, Marlow-not-Marjorie lesbian Canney saw in Newlyn 40 years later. In the meantime, she had moved to Paris and found the work of Piet Mondrian.

The effect was electrifying. One of the things that makes Moss stand out historically as an English artist is her untypical passion for European modernism. In 1927, the year she moved to Paris, the hottest group in London was the Seven and Five Society, its members still doggedly struggling to marry an outdated post-impressionist style to an outmoded local romanticism. Moss, by contrast, apprenticed herself to Fernand Léger, then experimenting with the mechanical mode of painting he had dubbed purism. Even this would not be radical enough for Léger's English student. In or about 1928, Moss saw her first Mondrian, and the die was cast.

Cast, as it turned out, in more ways than one. The Swiss abstract painter Max Bill recalled meeting Moss and her partner, Nettie Nijhoff – wife of the Dutch poet Martinus Nijhoff – at an opening at a Paris gallery in 1933. "Both," said Bill, "were dressed in flat hats with broad brims. They could have been Don Quixote and Sancho Panza." Flustered, the young man pointed to a group of pictures on the wall and burbled, "Thank goodness Mondrian has sent in such beautiful works!" There was a silence. Then Moss, the smaller of the two women, said, crisply, "Those are my paintings."

Amusing though it is, this story suggests two things. One is that Moss's gender-bending appearance, her membership of that ambiguous group known as garçonnes, bothered people. Presumably it was meant to. Posterity, though, likes neatness. Although nearly a quarter of a century had passed when Michael Canney saw Moss, his response to her is couched in the same terms as Bill's. She is an oddity rather than a person, not quite real. If she is memorable at all, it is as a footnote to the history of a man, Piet Mondrian.

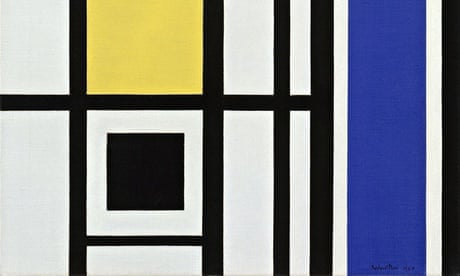

A quick walk around Howarth's Tate display will suffice to show how wrong this is. Moss's prewar paintings do look like Mondrians, in the way that some early Mondrians look like Derains. There is a difference between influence and imitation. Moss's take on neoplasticism is mathematically based, Mondrian's instinctual. When Moss – always "Miss Moss" to Mondrian – writes to explain her theories to him, he answers, stiffly, "Numbers don't make any sense to me." Her works look like his, but they also don't.

Nor was the influence all one-way. While other English artists, notably Nicholson and Hepworth, may later have appropriated Mondrian, only one English artist influenced him. In 1931, Moss introduced parallel double grid-lines into her paintings, an unorthodoxy that left the Dutchman dumbstruck. Nonetheless, in 1932, he painted Composition with Double Line and Yellow, now in Edinburgh. Debate rages over whether this is a response to Moss's invention, although, as ever, the discussion has focused on Mondrian rather than her.

Meanwhile, Canney's idea of Moss as aloof from English art has stuck. "That whole image of her comes from just one source," says Howarth, "but is it accurate? Maybe she was just in a bad mood the day she went into the gallery."

A much sounder reason for Moss's obscurity is that so little of her early work survives, and so much of her later work is hard to see. The chateau in Normandy she rented with Nijhoff was destroyed in the war, and most of her extant paintings with it. Moss's postwar work was left, at her death in 1958, to Nijhoff's son, Stefan, a Man Ray-trained photographer who worked under the name Stephen Storm and died in 1986. He in turn left it to his partner, who has seldom lent or shown the work since.

As to Moss's supposed aloofness, the facts do not bear it out. At Nettie's house in Zeeland when Holland fell in May 1940, she talked her way on to a tanker and escaped to Cornwall. Once there, and at Mondrian's prompting, she wrote to Ben Nicholson, proposing tea. He never replied. She wrote again, with the same result. Unbowed, Moss worked on alone, sticking to the abstraction that English artists – Nicholson at the time included – had given up on as too troublesome to sell.

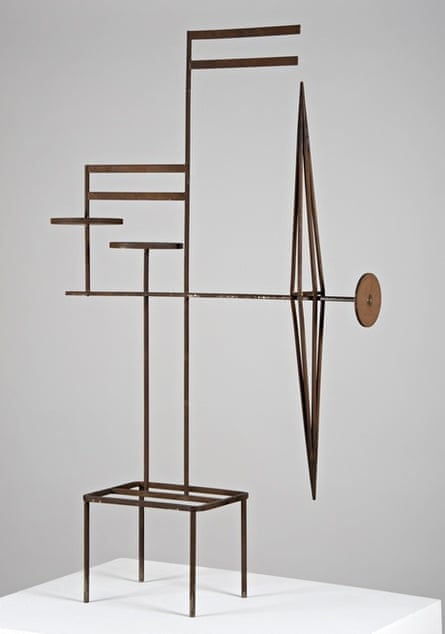

Moving into sculpture, she had solo shows at the Hanover Gallery in London in 1953 and 1958: the work, some of it in the Tate show, made no reference to Mondrian at all. With her fellow garçonne, the artist Paule Vézelay (née Marjorie Watson-Williams), Moss fought to open an English chapter of the French abstract club Groupe Espace. Their efforts were scuppered by Henry Moore and Victor Pasmore, appalled at the group's insistence on abstraction, subservience to Paris and the fact that its English chapter would be run by two women.

That Marlow Moss is ripe for rediscovery has struck the British art mainstream last of all. In Holland, she has been the subject of a novel, a ballet and an opera about her life with Nettie Nijhoff. She has also been claimed by queer theorists, intrigued less by her art than by her refusal to be a woman in a man's world. "During the Leeds show, I gave a queer tour of the gallery," says Howarth, laughing. "I started talking about the problems of Marlow Moss being seen only in terms of Mondrian, and a couple of women stopped me. 'Who's this Mondrian?' they said. It was great."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion