The Utah Lawyers Who Are Making Legal Services Affordable

A sliding-scale model plus a bit of creativity allows Open Legal Services to represent those with few other options.

In late 2013, Vicky, a single mother of two, was driving her then-boyfriend to an acquaintance's house in a small town north of Salt Lake City. Vicky (whose name has been changed to protect her privacy) thought her boyfriend was going to ask about some money owed to her, but, as she waited in the car, things went off the rails: The boyfriend entered the house without permission, tore the place up, and threatened its owner.

“Two minutes later,” as her attorney, Shantelle Argyle tells it, “the police pulled up behind her, ordered her out of the car—guns drawn—and took her to jail, where they interrogated her for about six hours about what they thought was this master drug cartel activity that was going on.” Vicky, who had no criminal record, knew nothing other than that she was soon charged as an accomplice with felony burglary, as well as simple assault. "She still didn’t even know what had occurred inside the house,” Argyle says.

Normally, Vicky’s legal options would have been pretty limited: She might have qualified for an already overburdened public defender, or she could have paid hundreds of dollars an hour—thousands in total—to a defense attorney. Instead, she paid $40 an hour—$678 in total—to a nearby firm in Salt Lake City, Open Legal Services, launched by Argyle and Daniel Spencer, two University of Utah law graduates, a few weeks earlier. After significant negotiation and fact-finding, Argyle got prosecutors to agree to a fair deal: They dismissed the felony charge outright, and Vicky pled to the misdemeanor assault charge because she knew that her boyfriend had a temper. She’s complied with probation since, and will be eligible to have the misdemeanor expunged in a few years.

Like more and more new lawyers, Argyle and Spencer graduated into a demoralizing job market, especially for jobs in public-interest law. So they decided to start a small nonprofit firm of their own, with four full-time equivalents and two part-time volunteers, catering to local, middle-class clients in a creative way. Instead of providing representation for free and surviving on grants, they decided to charge for their services.

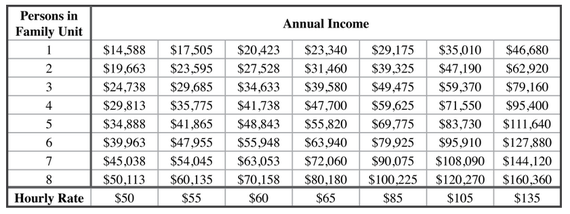

But instead of charging a flat fee, they index their hourly rates to each client’s income on a simple sliding scale that's published on their website. As their pricing table shows, a client's rate is determined only by family size and family income. At the low end, for example, a family of four earning $30,000 per year now pays $50 per hour for OLS’s services; at the high end, the rate for a family of four making $95,000 per year is $135. As OLS’s average hourly fee to date—$55—shows, their client base thus far has skewed toward the lower side of the matrix. (OLS will only take clients whose household income is between 1.25 and 4.25 times the poverty line. In Utah, half the state's population falls in that range.)

OLS is an intriguing response to two related problems: the feasibility of legal guidance for everyone but the rich, and the current glut of lawyers. That second problem should solve the first, but—for reasons I discussed recently in a longer piece—it hasn’t. In short, that's the case because expanding legal complexity and the bar’s “restrictive guild-like ownership structure of the business" have given American lawyers immense pricing leverage.

As a result, self-representation rates are high (in domestic violence cases, they often exceed 90 percent), while many Americans, as law professor Gillian Hadfield has illuminated, simply give up on claiming their legal rights because they can’t afford a champion. This is discouraging: “A growing body of research indicates that outcomes for unrepresented litigants are often less favorable than those for represented litigants,” notes one federal study.

Argyle, Spencer, and David McNeill—a recent Utah M.B.A. who oversees the firm’s business strategy—believe that OLS’s nonprofit status and its unusual pricing approach combine to make the firm a successful answer to those problems.

As a nonprofit, OLS is, of course, exempt from many taxes. Its lawyers also are eligible for the government’s Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, which wipes out the balance of their federal student loans after 10 years of monthly payments—an important subsidy. “The check you get from Uncle Sam in ten years is well worth what you paid in a lower salary equivalent,” Argyle says.

OLS's nonprofit status also allows it to get referrals from a number of sources, including courts, other nonprofits, and the state Bar. And it encourages businesses to help them out: not only are they a good cause, but contributions are tax-deductible. A private investigator, Argyle mentioned, offers the firm heavily discounted rates; other supporters have upgraded OLS’s databases and worked on the firm’s website for free.

The firm’s unusual pricing system provides a further edge. By indexing its hourly rate to clients’ incomes, OLS is doing something similar to what economists call “price discrimination”—charging different prices to different groups based on their willingness to pay. But customers’ ability to pay rarely figures in directly when firms price discriminate: A restaurant may offer a price for seniors based on the assumption that seniors have less disposable income, but you’re out of luck if you’re a middle-aged person on a senior citizen's budget. OLS’s model is more finely tuned, and more responsive to people’s needs. Each step up the income ladder, people who can pay more subsidize those who can’t.

Earning their fees directly, meanwhile, frees OLS from a lot of bureaucracy and unpredictability. McNeill recalls volunteering with Utah Legal Services, a local legal aid firm subject to onerous reporting obligations because it took money from the federal Legal Services Corporation. (The nation’s 134 LSC-funded legal aid programs are likewise congressionally required to turn down many clients, including people in prison and some immigrants, both documented and undocumented.) “The Innocence Project here in Salt Lake just lost their only staff attorney because their grant was not renewed!” Argyle notes. “And that organization does so much good in trying to get innocent people out of prison…We just did not want that for our people or for our clients.”

Charging everyone also ensures that all clients have skin in the game. Legal aid firms, McNeill argues, sometimes have issues with people “drain[ing] out a bunch of time and staff” on less-than-pressing problems. Charging fees, in turn, “keeps everybody accountable: It keeps us accountable to the client because they’re paying us—and it keeps them accountable because they’re paying us.”

Argyle and Spencer have made the model work by keeping costs low—including their own salaries, which just recently eclipsed $40,000 per year. Argyle does most of the firm’s billing, Spencer built and maintains the client database, and McNeill currently volunteers his time. Their office is downtown, McNeill notes, but in the basement of a hundred-year-old building. They get surplus computers and printers from the University of Utah and desks from a local thrift store.

They’re also able to give some work back to clients, declining the billable hours that profit-seeking firms often seize. In many family law cases, Spencer notes, clients need to file a supplemental affidavit offering their version of events. Many attorneys, he explains, “basically take the facts of the case, carefully wordsmith something that reads like a lawyer wrote it, and then have the client sign off on it.” OLS has the client draft the affidavit—“they’ll come back to us with a beautifully written and very passionate draft,” says Spencer—and then provides minor edits. “That’s one way that we can take something that many attorneys will spend an hour-plus on and reduce that down to just a five- to 10-minute edit job.”

The OLS team only knows of one firm that uses the same business model—Access Justice in Minnesota—and I'm aware of only a handful of others. Given its merits, why is OLS’s sliding-scale model so rare? Part of the reason is that it doesn't maximize profits—you can’t get rich running it. You also can’t help the people with the most urgent needs: those below the poverty line who are failed in criminal matters by the woefully underfunded public defender system, who are turned away from LSC-funded programs about half the time because of similar funding constraints, and who have no chance of affording even OLS’s rates, where total billings per case average roughly $300. Those rates are tiny relative to the industry standard, but they can even be daunting for members of the middle class, squeezed as they are.

One former legal aid executive director from New Hampshire, John Tobin, told me that his firm had toyed with initiating a sliding scale, but then he saw a statewide cost-of-living study and concluded that most of the potential clients “couldn’t afford to pay even a little bit.”

So far, however, OLS has not had problems with demand. The firm is currently managing 120 cases and adding about 10 new clients per week. (It helps that Utah’s cost of living is relatively low.) They just hired their fourth attorney, as well as a full-time paralegal/secretary. As they scale up, they believe they’ll be able to pay new associates more than $50,000 per year with benefits—a competitive salary—assuming each bills at least 25 hours per week, which is a fraction of what many corporate lawyers have to bill.

Meanwhile, they’re leveling a playing field that has been notoriously uneven for years, serving a constituency—the modest-means middle class—that often feels itself forgotten between attempts to cater to the rich and aid the poor. In family law, Spencer points out, “A large part of what we provide is leverage for a client who has extremely modest means, but may be going up against a spouse or a former spouse…who has a much higher income, and can afford to pay one of these big firms.”

Argyle, who previously dreamed of working as a public defender, notes that the leverage OLS offers is powerful in criminal law, too. “As a public defender, I never would have seen the kind of results that I’ve been getting on my criminal cases, and part of that is the bandwidth that we have,” she says. Reflecting on Vicky’s case in particular, she adds, “Public defenders will not go and interview co-defendants who are in jail. They don’t negotiate with prosecutors over email. They don’t have the resources.”

Others working on access-to-justice issues have started to take notice. The OLS team says they've received calls from the American Bar Association’s president-elect, the Colorado State Supreme Court, and the Montana and Washington State Bars.

They’re eager to see their model catch on. “We want the new attorneys coming out who can’t find jobs to recognize that you don’t need…the giant desk in the corner office. You don’t need the Bentley with your diploma that we were all promised," Argyle says.

McNeill takes a more analytical, but nonetheless similar, view: “This is a huge untapped market on the one hand, and we have an overproduction of lawyers on the other. So we’ve got the supply of lawyers, we’ve got the demand of work. We just need an entity that could bring the cost down to connect the two. And I think this is it.”