NPR and EdWeek’s series about an all-boys school focused on restorative justice is occasionally moving — but also flawed and frustrating.

By Joseph Williams

There’s nothing particularly innovative about “Raising Kings: A Year of Love and Struggle at Ron Brown College Prep,” the three-part series reported by NPR’s Cory Turner and Education Week’s Kavitha Cardoza that wrapped up last week.

The experience “Raising Kings” takes listeners through – the first year of a new school trying to do things dramatically differently – is familiar to any regular consumer of education journalism. And embedding reporters in a school to explore subtle dynamics is a technique so common that the Education Writers Association has its own tip sheet on how to do it effectively.

And yet, I found myself getting emotional during the second episode of the series when Amaru, a 17-year-old freshman who’s no stranger to trouble and is barely afloat academically, heads to the administration office.

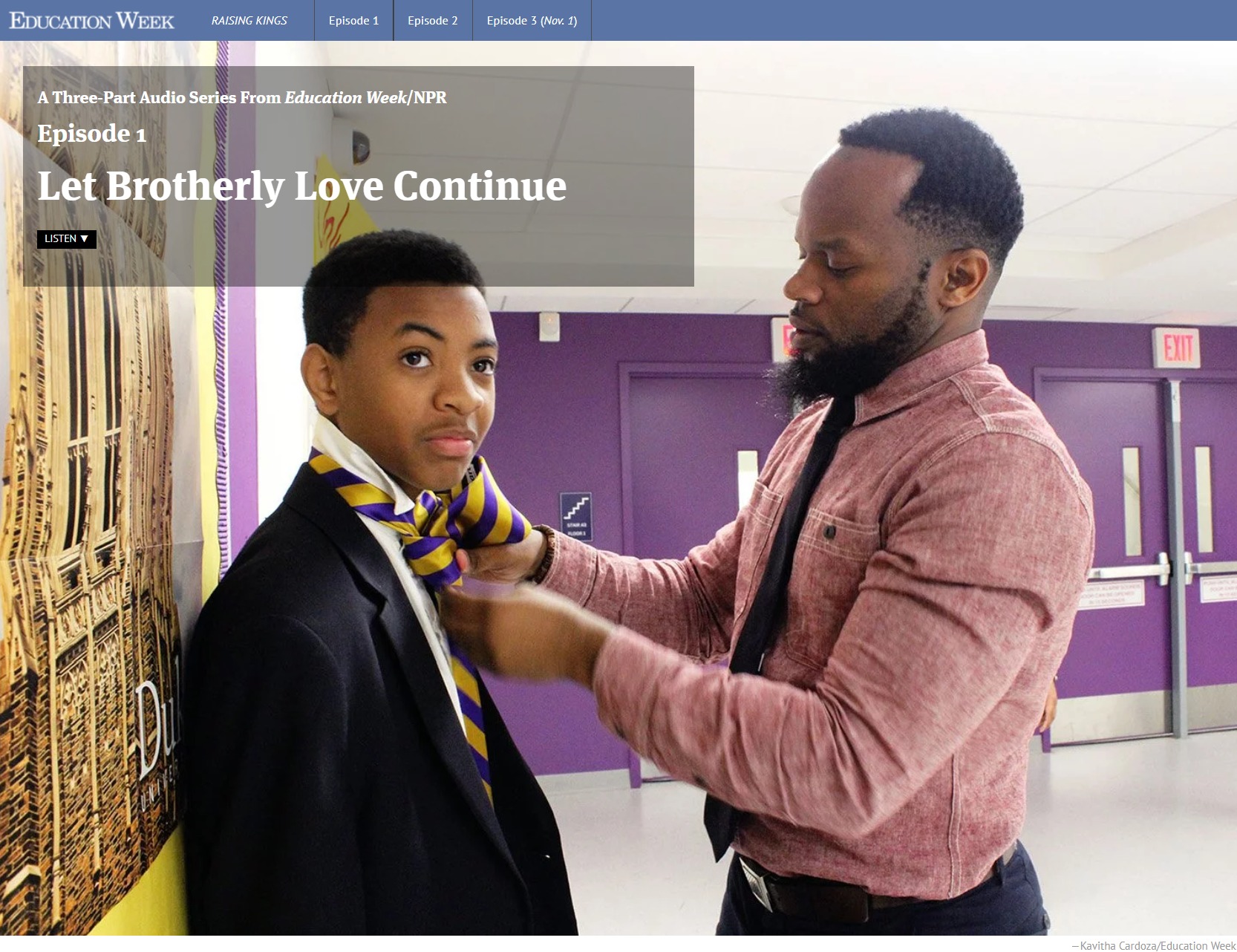

Amaru [we think that’s how to spell his name] had already been in a fight that shredded his school-uniform necktie and gotten into an argument with a teacher. It’s just the latest in a series of disciplinary strikes against him. However, before Amaru’s arrival, the school’s C.A.R.E Team – on-campus counselors and intervention specialists – decide not to suspend or expel him, or even read him the riot act. Instead, Amaru gets a surprise birthday party.

“Happy birthday, Bruh!” one teacher shouts, using Amaru’s signature one-word response. Principal Ben Williams ribs Amaru by repeating the word “bruh” in the melody of the birthday song.

The party leads to a frank discussion about Amaru’s future. And when the young man talks of a high school diploma, college degree and a career as a mechanical engineer, these same educators must now deliver a crushing reality check.

“For you to be here like we want you to be – like you share [with us] that you want to be – you got to work,” says Charles Curtis, the C.A.R.E. Team leader. “You got to work real hard at being a leader, at slowing down.”

The scene ends with a rare moment: a roomful of African-American male educators tell a troubled young black man that they love him. “I love y’all, too,” he mumbles.

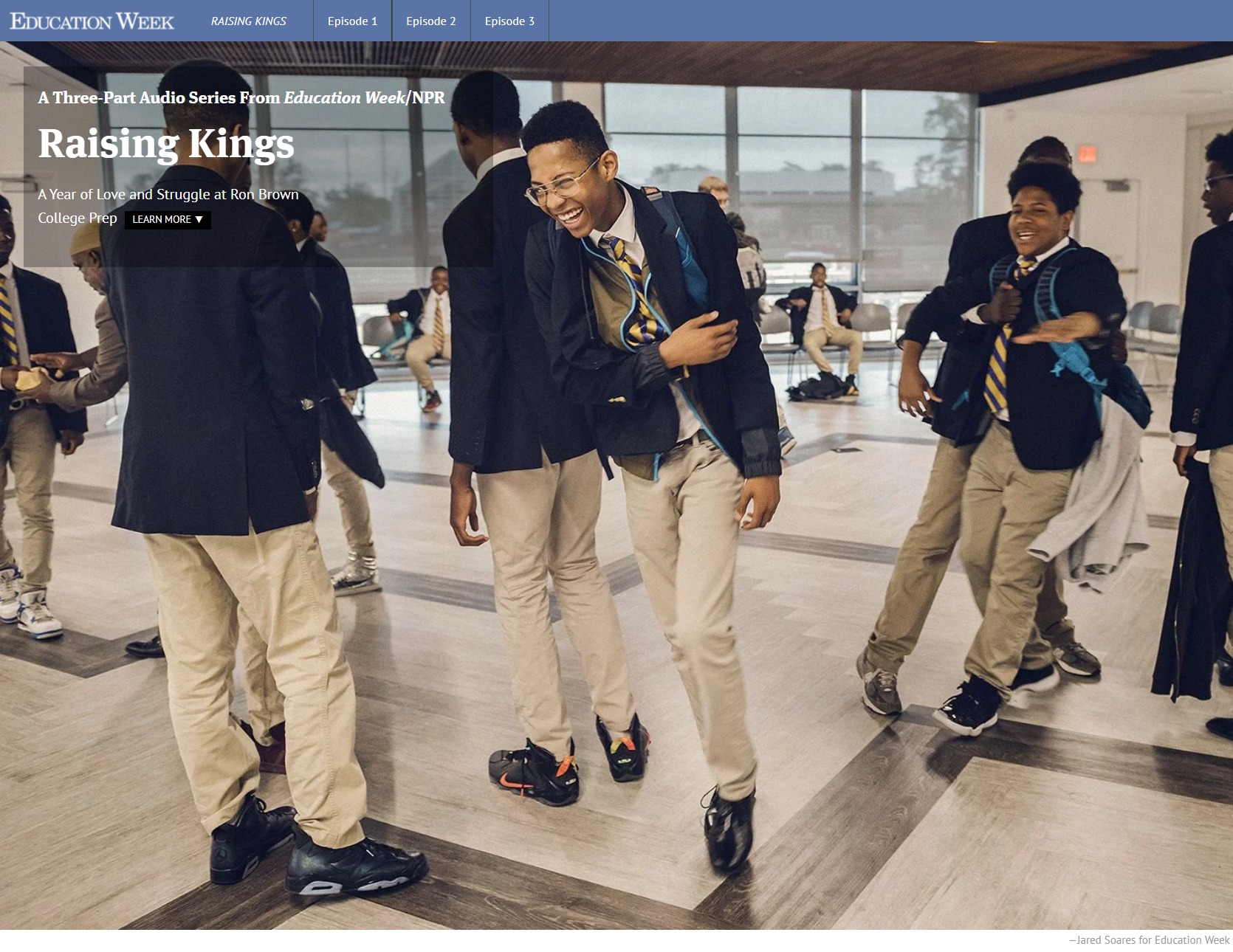

Cover image from EdWeek’s “Raising Kings” project page.

As a longtime journalist and the father of an autistic black teenager who just started high school, this moment was heartbreaking and infuriating at the same time. Being black and male in America is hard enough for the exceptional. Yet even a school set up specifically to lift kids like Amaru can’t reverse a lifetime of being let down: by disappearing fathers, by the public school system, by themselves. Amaru’s path is uphill and littered with boulders.

The scene also crystallized what I loved and found frustrating about “Raising Kings.”

The work put in by Turner and Cardoza shows through clearly. Ron Brown’s staff and students clearly trusted the reporting duo. The two reporters didn’t shy away from difficult and uncomfortable moments. They used data to underscore how the school’s mission is simultaneously critical and problematic. They added to the depth of the experience by partnering up with Code Switch, NPR’s podcast about race and culture.

Yet despite all this, the series – three long segments presented over the course of two weeks – felt thin on the ear-catching drama of the scene with Amaru. And the informal podcasting techniques, including banter between Cardoza and Turner, was a bit gimmicky and distracting to me. I wanted the kind of sophistication I heard when “This American Life” told us about five months in a tough Chicago high school. But that’s not what I got.

All three parts of the Raising Kings special series can be found here. The EdWeek project page includes video snippets and other materials.

Set in a gritty D.C. neighborhood where poverty, gunfire, incarceration and death are facts of life, Ron Brown’s founders insist on diversity among its black male population. The school recruits middle-class as well as poor kids, seats high achievers next to kids who are in crisis academically, sets high expectations for everyone, and trades zero-tolerance discipline for unconditional love. Nearly all of the educators at the school are black men.

There’s more than a little justification for Ron Brown’s radical, focused approach. African-American boys are significantly more likely than whites to be kicked out of school for minor infractions, only about half are likely to receive high school diplomas, and nearly all are likely to finish school without seeing an African-American man at the front of the classroom – a potential role model for young men who desperately need them.

Williams, the principal, is the abandoned son of a drug addict who earned a doctorate in education and wholeheartedly embraces the school’s groundbreaking mission. Shaka Greene, director of the math department, grew up poor but is a no-excuses disciplinarian – and the school’s most popular teacher by far. Curtis, the C.A.R.E. Team leader, is a psychologist who has seen his share of trouble, yet believes in talking out conflicts.

Even in such an unusual school, it can be hard for journalists to bring nuance and depth amid racial tropes: heroic, anti-establishment teacher; crusty yet golden-hearted principal, promising but troubled student on the razor’s edge between the classroom and the streets. Fortunately, those stereotypes are absent – mostly – from “Raising Kings.”

In the first episode (43:00), the new school opens amid great fanfare, sky-high expectations, a $1-million discretionary budget, and intense if unspoken pressure. A clutch of local and national TV news crews cover opening day, when District of Columbia Mayor Muriel Bowser greets 100 ninth-graders – the Class of 2020 — in navy blazers, tan slacks and purple-and-gold neckties (to facilitate the startup, the first class is solely freshmen). The faculty indoctrinate them in the school’s call-and-response rallying cry: “We are! All in!”

When the news cameras move on, the real work unfolds and the drama of “Kings” begins.

In the second episode (47:00), the teachers and the students both realize the daunting (and perhaps unrealistic) task ahead: Treating undereducated kids and their college-bound peers to the same standard, and demonstrating love and restraint to boys who aren’t familiar with either concept. By midyear, cracks begin to appear in the school’s optimistic foundation, and reality sets in. A Ron Brown student punches a security guard but faces no harsh consequences; another gets shot and wounded during an after-hours dice game.

Meanwhile, a sizeable percentage of students aren’t academically prepared — or don’t have the at-home stability — to tackle high school, much less college. And some students from more advantaged families are getting fed up and transferring out of the school. “Some kids are used to certain things — how they survive in their community,” says a parent who’s withdrawing her son. “That’s not where my son is from.” (The series should have spent more time on the middle-class kids at Ron Brown and the challenges they faced; that’s a side of the black educational experience that’s too rarely explored.)

In episode three (49:00), as the year winds down, the tensions among the educators reach a dramatic showdown. Teachers who took pay cuts to work at Ron Brown grumble about a district-wide mandate: Students will advance to the next grade even if they didn’t do enough passing work to qualify. Disgusted by the notion of passing unprepared kids on to the next grade, math teacher Greene decides to call it quits. Behind closed doors, a raw debate between Greene, principal Williams and some administrators ensues.

The staff question whether Green is really “all in” for the mission, accusing him of taking the easy way out like so many of the boys’ absentee dads. But Greene is having none of it: Pushing forward kids who are so far behind, he tells Cardoza, is just as harmful, if not worse, than failing them.

“To use this almost like a guilt trip – ‘I’m going to make you feel bad for making this decision, you’re abandoning the children,’ ” he tells Cardoza, his voice trailing off. “And I could have said in the moment, ‘Well, you abandoned them first with this bull—t policy.’”

EdWeek project director Lesli Maxwell, reporter Kavitha Cardoza, and NPR education reporter Cory Turner.

Despite moments like these, I came away from the series feeling less than entirely satisfied.

I wish I could have been a fly on the wall in that meeting. It was so frustrating. Turner and Cardoza seemingly got access to everything — except the one scene I wanted to hear most. They seemed to know they’d missed a key moment, and their reconstruction of the debate was good. But it’s not the same as hearing it firsthand as it happened. (And it reminded me again of the question I’d had throughout the series: whether a black reporter might have been able to provide additional insights, experiences, and even access.)

NPR and EdWeek declined to provide any reporters or editors to be interviewed for this piece.

On paper, the collaboration between NPR’s education team, EdWeek, and the Code Switch podcast seems like the perfect vehicle to bring an important story into the podcast age and hook a younger demographic. However, the introductory conversations between Code Switch hosts Gene Demby and Shereen Marisol Meraji framed each episode with background information. And I found their banter distracting and unnecessary. It was too casual, and the tone felt like it was undermining the gravity of the piece.

Overall, there were too many journalists’ voices. There needed to do more showing, less telling. But the journalists’ voices kept stopping to interpret things at the expense of students’ and teachers’ voices, shortchanging the narrative drama. In nearly three hours, there were just three memorable moments: the opening scene with the intervention team and the student’s mother, the impromptu birthday party in the second episode, and the showdown among educators over the social promotion policy. There could have been several more.

Ultimately, “Raising Kings” left me agitated – not just because of its cool-podcast hipster vibe. My mind kept wandering behind the curtain, so to speak, to what I saw as the fundamental problem:

Kids at Ron Brown College Prep – and millions of other African-American boys just like them nationwide – need top-to-bottom school reform and structural changes to housing and economic policy. Until that happens, the lofty goals of the school and the Herculean work of its paradigm-shifting educators won’t fare much better than – as one teacher put it – a doctor using a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound.

“I came in here with such high hopes that we were changing the narrative in all areas,” said English teacher Aaron Smith. Some of his students had floundered, despite all his efforts to push them, and were being passed on to 10th grade like in any other DC public high school.

In presenting the ideas and aspirations of Ron Brown College Prep so enthusiastically and even optimistically from the start, even adopting the school’s language (calling students “kings,” for example), Cardoza and Turner set listeners up for disappointment just like the school sets kids up for failure.

It’s a common challenge when reporters embed with their sources – and an understandable sentiment given writers’ desires to report possible new ways of addressing longstanding problems. But it ultimately does its listeners a disservice.

Joseph Williams is a longtime journalist who writes for US News & World Report covering the Supreme Court and for various other publications. He can be reached on Twitter at @jdub321. Previously at the Grade: Why DeVos Commencement Coverage Was So Basic.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joseph Williams

Joseph Williams is a longtime journalist who writes for US News & World Report covering the Supreme Court and for various other publications. He can be reached on Twitter at @jdub321.