What the 'Crack Baby' Panic Reveals About The Opioid Epidemic

Journalism in two different eras of drug waves illustrates how strongly race factors into empathy and policy.

Epidemics are hard to cover. Navigating the gaps between the private, personal, and societal and managing to be relatable while also true to science is a tough part of health reporting, generally. Doing those things in the middle of public panic—and its attendant misinformation—requires deftness. And performing them while also minding the social issues that accompany every epidemic means reporters have to dig deep, both into multiple disciplines and into ethics. With multiple competing narratives, politics, and the sheer scale of disease, it’s often easy to forget the individuals who suffer.

That’s why I was struck by a recent article in the New York Times by Catherine Saint Louis that chronicles approaches for caring for newborns born to mothers who are addicted to opioids. The article is remarkable in its command and explanation of the medical and policy issues at play in the ongoing epidemic, but its success derives from something more than that. Saint Louis expertly captures the human stories at the intersection of the wonder of childbirth and the grip of drug dependency in a Kentucky hospital, all while keeping the epidemic in view.

One particular passage stands out:

Jay’la Cy’anne was born with a head of raven hair and a dependence on buprenorphine. Ms. Clay took the drug under the supervision of Dr. Barton to help reduce her oxycodone cravings and keep her off illicit drugs.

“Dr. Barton saved my life, and he saved my baby’s life,” Ms. Clay said. She also used cocaine on occasion in the first trimester, she said, but quit with his encouragement.

[...]

For months, Ms. Clay had stayed sober, expecting that she’d be allowed to take her baby home. Standing in the hospital corridor, her dark hair up in a loose ponytail, she said, “I’m torn up in my heart.”

Generally, treatment for drug-dependent babies is expensive and can go on for months. Nationally, hospitalization costs rose to $1.5 billion in 2012, from $732 million in 2009, according to researchers at Vanderbilt University.

In the space of a few paragraphs, the story introduces a mother and child and the drug dependency with which they both struggle, and also expands its scope outwards to note the nature of the epidemic in which they are snared. It doesn’t ignore the personal choices involved in drug abuse, but—as is typical for reporting on other health problems—it considers those choices among a constellation of etiologies. In a word, the article is humanizing, and as any public health official will attest, humanization and the empathy it allows are critical in combating any epidemic.

The article is an exemplar in a field of public-health-oriented writing about the opioid crisis—the most deadly and pervasive drug epidemic in American history—that has shaped popular and policy attitudes about the crisis. But the wisdom of that field has not been applied equally in recent history. The story of Jamie Clay and Jay’la Cy’anne stood out to me because it is so incongruous with the stories of “crack babies” and their mothers that I’d grown up reading and watching.

The term itself still stings. “Crack baby” brings to mind hopeless, damaged children with birth defects and intellectual disabilities who would inevitably grow into criminals. It connotes inner-city blackness, and also brings to mind careless, unthinking black mothers who’d knowingly exposed their children to the ravages of cocaine. Although the science that gave the world the term was based on a weak proto-study of only 23 children and has been thoroughly debunked since, the panic about “crack babies” stuck. The term made brutes out of people of color who were living through wave after wave of what were then the deadliest drug epidemics in history.

Even the pages of the Times weren’t immune from that panic. A 1989 article on studies of crack babies actually begins to note the limits of scientific evidence, but continues to speak of the children’s “emotional poverty” and also continues the oft-repeated maxim that crack babies would “present an overwhelming challenge to schools, future employers and society.” Another article from 1990 predicts an onslaught of up to 4 million crack babies whose “neurological, emotional and learning problems will severely test teachers and schools.”

That reporting, though, is still relatively empathetic and grounded in science compared to what other outlets ran at the time. A 1989 Washington Post column features quotes like “these mothers don't care about their babies and they don't care about themselves,” and claims that “some young mothers do not believe that crack is bad for their babies.” Another 1989 column in the Post by Charles Krauthammer was widely cited in the panic and claimed that crack babies constituted “a bio-underclass, a generation of physically damaged cocaine babies whose biological inferiority is stamped at birth.” A May 1991 Time magazine cover declares “their mother used drugs, and now it’s the children who suffer.”

A 1990 Rolling Stone article starts to attempt some empathy towards the plight of children born with dependencies, but ends up here:

Not only does it make babies only a mother could love, it wipes out that love as well. When pregnant crack addicts are asked to draw a self-portrait, they never draw themselves pregnant. They turn away from ultrasound pictures with revulsion. Drug counselors now look back to the days of heroin families with something verging on nostalgia. Heroin mothers could still buy groceries, they still occasionally gave a kid a bath.

Those sentiments, and the fears of criminal black youth that they created, ran wild in national and local media. The lead story in the September 18, 1990 issue of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch cites a “Disaster In Making: Crack Babies Start To Grow Up.” The fear of an ascendant group of millions of crack babies contributed—again with only a specter of evidence—to reports of “super predators” in black neighborhoods. And these are just mainstream print journalism examples. Television, tabloids, and politics all of course ran hotter and more sensational.

Predictably, reporting on the crack epidemic that focused not on public-health issues but the future criminality of crack babies and the culpability of their mothers led to politics and policies that incarcerated those children and their mothers.

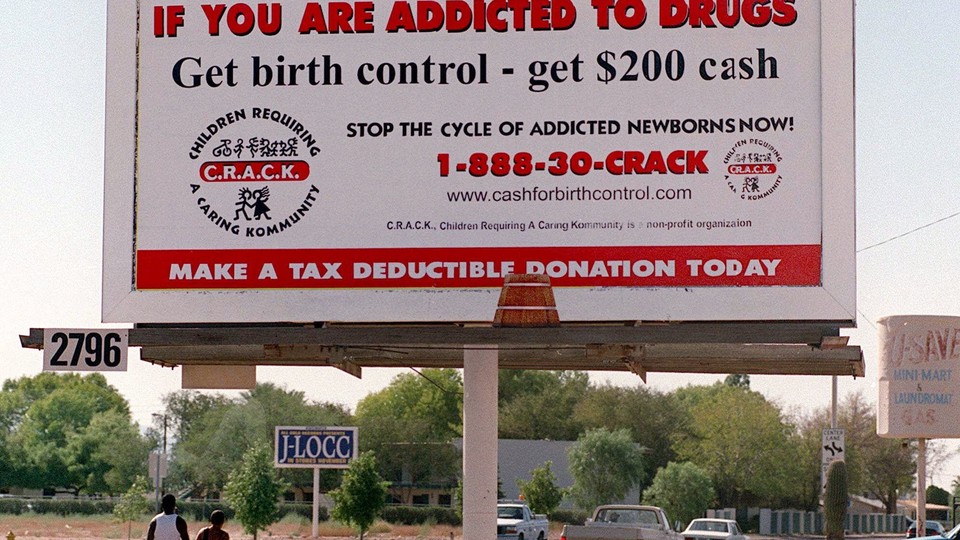

Even in 1990, legal reviews and lawsuits found that state and local prosecutors were basically inventing statues and offenses out of whole cloth in order to imprison mothers who gave birth while addicted to drugs. Authorities in most states, instead of crafting public-health interventions and bolstering safety nets to combat drugs, simply leveraged the threat of incarceration or child removal against mothers. And, of course, lingering fears about the coming crack baby and “super predator” generation gave the country laws that disproportionately incarcerated black people, like the 1994 Crime Bill, which passed with massive margins, public approval, and bipartisan support.

Today is a different time than the late ‘80s and ‘90s. Public-health science has advanced and has taken more of a hold in public discourse. Thanks in part to scholarship that has laid bare the effects of racialization on society, journalism is more attuned to the kinds of dog-whistle language that pervaded not only the crack epidemic, but the heroin epidemic before it. Still, although there have been strides in understanding, there have been few major correctives to the way drug problems in black communities were perceived, and to the policies that those perceptions created.

Even as the country grappled with that, the face of the epidemic changed. A certain racial empathy gap, while by no means the sole driver of journalism and policy today or 30 years ago, is undoubtedly at the center of the conversation around drugs in America. Today’s opioid epidemic presents a mostly-white face to the world, and the larger “epidemic of despair” tends to target communities in vaunted “Middle America,” as opposed to inner-city Baltimore and Detroit. And with that changing face comes better results. Instead of wide-scale carceral panics and schemes to imprison addicted mothers, the country has considered a public-health approach, as signaled in the latest draft of the Senate health-reform bill, which would appropriate $45 billion to public health programs to fight the opioid crisis.

That’s not to say the country’s fully embraced the wisdom of public health, even for white patients. The war on drugs is still raging, reinvigorated by Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Criminalization of women who give birth while addicted still penalizes even white women. And that $45 billion in the Senate package also comes with massive cuts to Medicaid, which is the largest insurer at the front lines of the crisis. But responsible journalism like Catherine Saint Louis’s contributes to a sense that the tide is turning, and that perhaps the country will figure out a sensible drug policy. At least, for these victims.