Indian anthem Jana Gana Mana turns 100

- Published

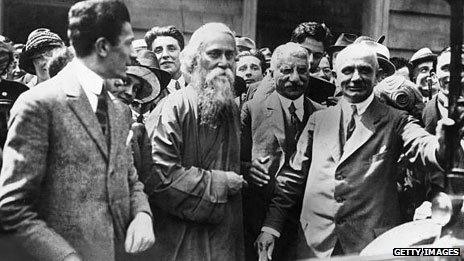

Exactly 100 years since it was first sung in Calcutta, the song that later became India's national anthem has braved numerous controversies. Shamik Bag explores Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore's Jana Gana Mana and its vision of Indian universality.

The song has been as feted as it has been vilified. Jana Gana Mana, India's national anthem, has seen millions on their feet, standing to reverential attention, every time it is played.

Among its critics are those that consider the song to be deferential to the British monarchy; others find it fails to fully reflect races and regions.

But 100 years after Tagore - the first Asian winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 - wrote and performed the song on 27 December 1911 at the Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress, Jana Gana Mana has maintained its grip on the Indian public and political imagination.

Co-ownership claims

Celebrity endorsers like Academy Award-winning composer AR Rahman, who released an album based on Tagore's tune, gave the century-old song a chic generational twist.

Bollywood blockbuster Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham, starring superstar Shah Rukh Khan, also used the national anthem to tear-jerking effect.

On the other hand, political controversies, clamour for changes in lyrics by regional politicians, and even claims of co-ownership of the composition have kept Jana Gana Mana in the news.

Even as cultural organisations like the Mumbai-based Pancham Nishad plan to commemorate the centenary of the song, one MP from Assam last month demanded the inclusion of the state and the north-eastern region in the song.

Kumar Deepak Das said that Tagore incorporated British-ruled regions of India in Jana Gana Mana when much of the north-eastern region was outside British authority.

"There are insurgency and secessionist movements in the north-east. People there often feel neglected. If the Indian government agrees to modify the national anthem, such measures can resolve the feeling of alienation," he said.

Jana Gana Mana was selected as the national anthem of India in 1950 after considerable debate overruled Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay's popular Bengali song Vande Mataram in the face of Muslim opposition.

In 2005, a petition filed in the Supreme Court demanded the inclusion of the word Kashmir in the national anthem and the deletion of Sindh, which became part of Pakistan following Partition.

That the national anthem, written in Sanskritised Bengali by Tagore, continues to galvanise a spirit of regional and racial identity became apparent after India's Sindhi community jointly opposed the deletion, claiming the word Sindh to be representative of the community.

The Supreme Court ruled in favour of the community and against the petition - it said that a national anthem was "a hymn or song expressing patriotic sentiments or feelings" and "not a chronicle which defines the territory of the nation".

'Unbounded stupidity'

Controversy shadowed Jana Gana Mana from the day of its first rendition in 1911 at the Congress session in Calcutta.

King George V was scheduled to arrive in the city on 30 December and a section of the Anglo-Indian English press in Calcutta thought - and duly reported - that Tagore's anthem was a homage to the emperor.

The poet rebutted such claims in a letter written in 1939: "I should only insult myself if I cared to answer those who consider me capable of such unbounded stupidity."

The official report of the Congress session, where Jana Gana Mana was submitted as a patriotic song, and the reports of other local newspapers also countered the criticism of the song's patriotic credentials.

There have been other, high-profile and intellectual adherents of Tagore and Jana Gana Mana.

Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi considered the song to have "found a place in our national life" while India's first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru noted that Jana Gana Mana was "a great national song… also because it is a constant reminder to all of our people of Rabindranath Tagore".

In India's National Anthem, published in 1949, author and Tagore scholar Prabodhchandra Sen documented the strong anti-British sentiment in Tagore's work and chided the misreporting by the Anglo-Indian press.

Sen pointed out the broader vision of Jana Gana Mana as a song that glorifies the motherland and is a "hymn in praise of the lord of the universe, the dispenser of human destiny" - a status not mortally possible for any human being to achieve, including the British king.

A later publication - the Rabindra Kumar Dasgupta-authored Our National Anthem in 1993 - backed Sen's theory.

Barun De, historian and Tagore National Fellow at Victoria Memorial Hall, says Jana Gana Mana envisages an India where disparate cultures, languages, races and religions have coalesced into one country.

India now has 28 states and seven Union Territories, there are 22 officially recognised languages and 1.2 billion people.

Back in the 1940s, some theatres in Calcutta would play the British national anthem, God Save the Queen, before film screenings.

Mr De remembers his nationalistic-minded mother getting hissed at by Anglo-Indian ladies for not standing up.

Mr De says: "While Tagore was averse towards rigid patriotism, Jana Gana Mana represents nationalism's broadest idea. There is nothing chauvinistic about it. A hundred years later, it continues to appeal to India's democratic consciousness."

Shamik Bag is a Calcutta-based writer

- Published9 August 2011

- Published7 September 2006

- Published10 April 2007

- Published1 September 2006