Brain cells that die off in Parkinson's disease have been grown from stem cells and grafted into monkeys' brains in a major step towards new treatments for the condition.

US researchers say they have overcome previous difficulties in coaxing human embryonic stem cells to become the neurons killed by the disease. Tests showed the cells survive and function normally in animals and reverse movement problems caused by Parkinson's in monkeys.

The breakthrough raises the prospect of transplanting freshly grown dopamine-producing cells into human patients to treat the disease.

"Previously we did not fully understand the particular signals needed to tell stem cells how to differentiate into the right type of cells," said Dr Lorenz Studer at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre in New York.

"The cells we produced in the past would produce some dopamine but in fact were not quite the right type of cell, so there were limited improvements in the animals. Now we know how to do it right, which is promising for future clinical use."

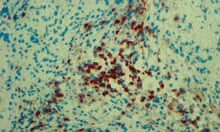

Parkinson's disease takes hold as cells that produce dopamine die off in part of the brain called the substantia nigra. This causes tremors, rigidity and slowness of movement, though patients may also experience tiredness, pain, depression and constipation, which worsen as the disease progresses.

The main treatments for Parkinson's are drugs that aim to control the symptoms by increasing the levels of dopamine that reach the brain and stimulating the parts of the brain where dopamine works. Some patients have wires surgically implanted into their brains that deliver electrical pulses to alleviate movement problems.

For around a decade, scientists have been trying to regrow nerve cells lost in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) from stem cells. However experiments in which dopamine neurons were created from mouse stem cells have not been successfully reproduced in humans. There have also been safety concerns, with signs that dopamine neurons developed from human stem cells can trigger the growth of tumours. As a result, clinical trials in humans have yet to start.

Dr Studer and his colleagues, whose work is published in the journal Nature, found the specific chemical signals required to nudge stem cells into the right kind of dopamine-producing brain cells.

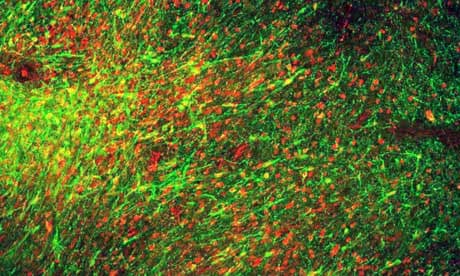

In a series of experiments, the team gave animals six injections of more than a million cells each, to parts of the brain affected by Parkinson's. The neurons survived, formed new connections and restored lost movement in mouse, rat and monkey models of the disease, with no sign of tumour development. The improvement in monkeys was crucial, as the rodent brains required fewer working neurons to overcome their symptoms

On the prospect of future human trials, Dr Studer said: "We now have the right cells, but to put them into humans requires them to be produced in a specialised facility rather than a laboratory, for safety reasons. We have removed the main biological bottleneck and now it's an engineering problem."

In the 1990s, doctors transplanted foetal brain tissue into Parkinson's patients to see whether it improved their symptoms. The results varied substantially, with some patients getting better and others experiencing runaway involuntary movements. Further work revealed that there was a window of opportunity to treat the disease: those who received transplants too early suffered side-effects, while tissue transplanted too late had no beneficial effect.

Parkinson's disease mostly affects the over 50s, but of the 120,000 people in Britain who have the condition, one in 20 is under 40 years old.

Kieran Breen, director of research at Parkinson's UK, said: "Stem cells carry a real hope for the treatment and potential cure of some people with Parkinson's. However, we need to be sure that the cells that are transplanted to replace the brain cells that have died will work correctly."

He added: "Researchers had already generated the right type of nerve cells from human stem cells to produce the chemical dopamine that is depleted in Parkinson's, but there were problems when the cells were transplanted into models of Parkinson's animals. The cells continued to grow and some transformed into tumours.

"In this study, the researchers used a different procedure to differentiate the stem cells into nerve cells. This time they remained as correctly working nerve cells, did not form tumours, and overcame some of the symptoms of Parkinson's in the monkeys.

"Stem cell therapy may still be some way off. However, this study has shown for the first time that it is possible to transplant nerve cells that work from human stem cells."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion