History is clear: Labour must lead an alliance for democratic reform

With planetary emergency looming, the left must lead a broad coalition: Labour’s defeat and the triumph of Johnsonism, part six.

Since 2017, the political right has successfully regrouped around a new hegemonic project which links public disillusionment with democracy to a nativist nationalist agenda. Its objective is pretty clear: to prevent any threat to finance, real estate or extractive capital emerging in response to the looming climate crisis and the demands of young people for jobs and homes. There is little question that the fight for these things and for democratic renewal will be central to left struggle for the decade to come. But before considering the implications of this new hegemonic project, it is important to understand the structural and institutional context that has allowed it to emerge so quickly.

This is the concluding article of a series on Labour’s December 2019 election defeat. In this final contribution, I will consider the strategic implications not just of Labour’s defeat, but of the Tory victory. I will look at the structural conditions that made that result so likely, and how the left might go forward from here.

A Pro-Tory System

It is normal for Labour supporters, members and activists to perceive the media as heavily biased against them. If they are sufficiently knowledgeable, then they will usually understand that the entire electoral system is similar slanted. What’s striking, however, is that they usually seem to imagine that somehow every part of the country’s political ecology – from Plaid Cymru to the ‘Daily Mail’ – consists of a general conspiracy against Labour. What this perspective misses is that these systems are not simply anti-Labour. What they are primarily is pro-Tory: and anti-everyone else (including, for example, Plaid).

This situation has been developing since the early 20th century, with the emergence of the modern Conservative party as the unified party of British ruling class. Since that time, the Tories have functioned as the party of British capital and of those other class fractions whose political orientation was defined by deference to it. This is of course a simplification, but it is broadly accurate.

The pro-Tory bias of the British media is abundantly and transparently clear. But it is worth reflecting on nonetheless. It’s not as if the Green Party, nationalists or Liberal Democrats get anything like sympathetic coverage in the UK media, even to the extent that their relatively small levels of electoral support would seem to warrant. Arguably the extreme nationalist right gets more support from mainstream media than do the Liberal Democrats.

As for the electoral system, this is complicated. Historically it has usually awarded more seats for the same number of votes to the Tories than to any other party. Occasionally this situation has been reversed in Labour’s favour. But, for example, when the latter situation obtained during the New Labour years, it was clear that the reason for Labour’s temporary advantage was that it had captured the votes of swing voters in marginal constituencies, the vast majority of whom were middle-aged, property-owning, conservative and individualistic in outlook.

In the 1990s, New Labour strategists were always very clear about what they had learned from decades of electoral failure for Labour: the First Past the Post system, as it operates in the UK, effectively hands full control over electoral outcomes to swing voters in ‘Middle England’, who are ideologically conservative and economically affluent. International comparisons tend to suggest that this is a feature of First Past the Post systems all over the world, because they punish political parties and movements with geographically concentrated support. Socialism was born in the cities and has always had its strongholds there, and so tends to suffer considerably at the hands of such a system.

But so do smaller parties with their support more evenly distributed, such as the Greens and Liberal Democrats. Here it is worth reflecting that since the early twentieth century, the Liberal party and its descendant – the Liberal Democrats – have largely functioned as a party of anti-Tory protest and social reform in localities where Labour has never had a strong presence. They have also been in coalition with Labour very regularly in the Scottish parliament (prior to Labour’s Scottish collapse), the Welsh Assembly, and in local authorities up and down the country. It is true that at some junctures they have also allied opportunistically with the Conservatives against Labour; and in recent years their national leadership has been captured by ideological neoliberals with their political base amongst the urban upper-middle-class, who tend to view Labour as their main antagonist. But broadly speaking they have suffered as badly as Labour from a system that is overwhelmingly biased in favour of the Conservative party; or at least in favour of a social constituency that is typically pro-Tory, only voting Labour when the party embraces an explicitly centre-right perspective.

The reality of this situation was fully manifest in 2017 and 2019. Under any fair voting system, Labour, Plaid, the SNP, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens would have been in a position to prevent the Tories and DUP from controlling the legislative agenda. If Labour had been willing to do a simple electoral deal with the other parties, they could have made this happen, at absolutely no cost to themselves. They weren’t, and so the system did its work, leaving May in control, while allowing her successor eventually to call another election in 2019.

At that election, as explained at the very beginning of this series, ‘Leave’ had a majority in an overwhelming majority of constituencies, bearing almost no relation at all to its overall support nationally. This was surely the ultimate expression of the fact that, whatever party actually manages to benefit from it, the UK electoral system overwhelmingly privileges older, white, propertied voters over all others. At the same time, the press has been increasingly oriented towards an extreme English nationalist position for many years, resulting in almost all of the newspapers coming out for Leave in 2016, despite the wishes of the then Tory leadership and of the most senior figures in the City of London.

Platform Nationalism

All of these circumstances created the context in which both the Conservative and Labour parties experienced the crisis of centrist neoliberalism. Under these conditions, the attempt by a right-wing faction to assert control of the political sphere, from within the institutional context of the Conservative Party, had every advantage.

Just consider the contrast between the ease with which Johnson expelled a whole bloc of anti-Brexit Tory MPs from the party, compared to the extreme difficulty that Corbyn had in exercising any discipline at all over the Parliamentary Labour Party. This was not because Johnson was a strong leader while Corbyn was a weak one. It is because a whole constellation of powerful forces (from the ‘Daily Mail’ to the hedge funds who funded the Leave campaign in 2016) was lined up in place to assist the transformation of the Conservative Party from a party of neoliberal conservatism under Cameron to a party of nationalist conservatism under Johnson. No such powerful apparatus was in place to assist Corbyn’s attempt to transform Labour from a party of neoliberal liberalism into a party of internationalist socialism. This is simply because no section of the capitalist class had any interest in assisting that project, while the class forces that did have such an interest were incredibly weak and disorganised.

Let’s consider some history. The New Labour years had coincided with the absolute peak of global neoliberal hegemony. During that time the historic Tory attachment to English nationalism had made it very difficult for the Conservative party to act as the agent for this phase of globalising hyper-capitalism. For a brief period, a pro-capitalist and socially-liberal faction of the Labour party had taken on the role of managing the further neoliberalisation of British society. But once that era ended, in 2008, the embedded institutional power of Toryism enabled the Conservative party, and its allies in the media, to reassert their authority over the political scene almost immediately.

Initially, this took the form of the party under Cameron taking on the mantle of New Labour centrist liberalism, while undertaking a direct assault on all of the social-democratic elements of New Labour’s legacy. But as the authority of neoliberal centrism continued to erode, a right-wing nationalist faction of the British ruling class – exemplified by Farage and eventually embodied by Johnson – were quite easily able to push and pull the Conservative party into line with their new project. Their counterparts on the left, by contrast, had an enormous struggle to fight in trying to win over the machinery of the Labour party and its few media allies (at ‘the Guardian’ and in some sections of broadcast media) from their unwavering commitment to liberal, cosmopolitan neoliberalism. That fight is still far from over.

Ultimately, the differences here are not difficult to understand. Corbynism was trying to take advantage of the crisis of neoliberal hegemony by transforming Labour into a vehicle of socialist anti-capitalist politics. Labour has arguably never really been that before, and no powerful section of British society had an interest in seeing that project succeed.

On the other hand, UKIP, the Brexit Party, the Tory right and the right-wing press were trying to take advantage of the crisis of neoiberal hegemony by turning the Conservative party back into a vehicle of pro-capitalist English nationalism. The Conservative party certainly has been that before, and clearly large sections of the capitalist class had a direct interest in seeing that project succeed, especially if the alternative was electoral success for Corbynism. The deep embeddedness of Toryism within the structures of the British establishment ultimately made Johnson’s task infinitely easier to undertake than Corbyn’s. It certainly made it easier to win an election as part of the process of undertaking it.

Johnson was able to take full advantage of this situation, while his campaign director, Dominic Cummings, was able to exploit the growing online ecology of the alt-right, which exists in a clear relationship of mutual reinforcement with ‘the Sun’ and ‘the Daily Mail’ here, as it does with Fox News in the US. Together, they were able to connect their extreme nativist politics with a general, and entirely justified, sense of disempowerment that many citizens share today. That sense of disempowerment often takes the form of a mere rejection of the very possibility of democracy and politics as such. Johnson and Cummings achieved all this by relentlessly circulating social media content that promoted the idea of Jeremy Corbyn as some kind of generic threat to national security, by insisting that Brexit was a process that could be easily resolved if only parliamentarians got out of the way, and by using social media and the press continually to stoke hatred, fear and resentment of immigrants. But above all, they operated simply by circulating so much contradictory information that people felt that there were no information sources they could trust, and no basis for rational deliberation whatsoever.

In 2008, when Johnson first became London mayor (overwhelmingly with the support of suburban voters from London’s Tory fringe), I wrote an article for openDemocracy arguing that a vote for Johnson was a vote against politics in general, in favour of a diffuse populist sentiment that was cynical of any real change being derivable from democratic processes; a sentiment that expressed itself as support for Johnson precisely because he believed nothing and took nothing seriously. In that article and over the next few years, I argued that the only way to challenge this form of anti-politics was for the leadership of the left to accept that, since the 1970s, we have seen a deepening crisis of our democratic institutions, enabled by and enabling the progress of neoliberal hegemony. I argued, against the assumptions of most of the mainstream left, that it was no good just to show by example that politics could really ‘work’: rather, I suggested, the crisis of democracy had to be acknowledged and addressed explicitly. It never was.

In 2016, Anthony Barnett and Adam Ramsay argued that the Brexit vote, at least for many working class voters, was itself an expression of desperate frustration with their lack of democratic agency: of the need to reject the authority of that unaccountable political class that had implemented the entire neoliberal programme since 1975 – whoever happened to have won the most recent election – and who had done nothing to restore the dignity of our post-industrial regions. In his immediate reaction to the election result, Ramsay expressed wholly justified and articulate frustration that this message had never been heeded by the party. As he explained, “Labour had made a retail offer to the electorate with a selection of attractive policies, but had never offered a coherent narrative that addressed their sense of collective democratic disempowerment”. The Brexit narrative, by contrast, did exactly that.

In a further brilliant analysis of the 2019 election result, Ramsay shows how Johnson and Cummings have succeeded in carrying the project of Johnsonian anti-politics to its logical conclusion. As he puts it, both their parliamentary antics and the digital propaganda that they subtly endorsed served to ‘make politics awful’, as the whole Brexit process came to be experienced by much of the public as a symptom of the dysfunction of British democracy. Then, having made politics experientially awful: they promised to end it. The promise to 'get Brexit done’ became a pledge not just to give the (neo)liberal elite a bloody nose, but to finally draw a line under the whole traumatising process of the country trying to make a democratic decision on an issue of momentous import, in a world in which nobody could be trusted. They created a kind of social machine within which people came to feel increasingly disempowered and dismayed by the very experience of democracy itself; and then promised to turn that machine off. On some level, of course, this is how reaction always operates: by making people feel that democracy is impossible. This is why depression, fear and futility are always affects that work for the right.

That is why it was never wrong for Labour to try to bring people a message of hope. But that message should have been the conclusion to a diagnosis of the problem: and the problem was the breakdown of democracy under neoliberalism. Johnson’s ‘Get Brexit Done’ mantra implicitly acknowledged that breakdown and its historical frame: promising some kind of resolution to both.

In a sense, there is nothing unique about Johnsonism at all. At least since the first Berlusconi administration, we have seen right-wing governments around the world combine a discourse and practice of anti-politics – implicitly denigrating the very idea of democracy – with an illiberal extension of corporate media control and a nativist social authoritarianism. ‘Populism’ is too simplistic a name for this type of politics, which is more distinctive and more technologically-specific than that name implies. It currently takes its most terrifying form in the shape of the Bolasnaro regime, and its murderous assault on the Amazon. In all of its contemporary iterations, the new form of anti-democratic reaction has been vastly enabled by our entry into a world of platform media and shady Facebook algorithms, delivering right-wing propaganda to nobody-really-knows how many people.

To be sure, the same technological processes have facilitated new forms of democratic and socialist resistance. We will need to make use of all of them if the planet is to have any hope of survival.

Labour’s Disastrous Electoral History

But we will also need something else: a clear, realistic and intelligent assessment of our current strategic situation, and of the political forces at our disposal. Let us make this very clear. The Labour party and the British trade-union movement have never, at any point in their history, been powerful enough to overcome Tory political hegemony on their own, for any sustained period.

In 1906 the Labour Representation Committee had to form a non-aggression pact with the Liberals to make its first serious breakthrough into parliament. In the 1920s Labour governments were only formed with Liberal support. In 1945 Conservative hegemony had been broken by the onset of war, which left Churchill needing Labour support to run the country, which gave the party a position within the wartime national government, from which it could commission the Beveridge report (again with Liberal support). Labour spent three years aggressively publicising Beveridge (literally hundreds of thousands of copies were published), before fighting an election with a manifesto based on it. No equivalent situation for Labour has ever obtained before or since, nor is it ever likely to.

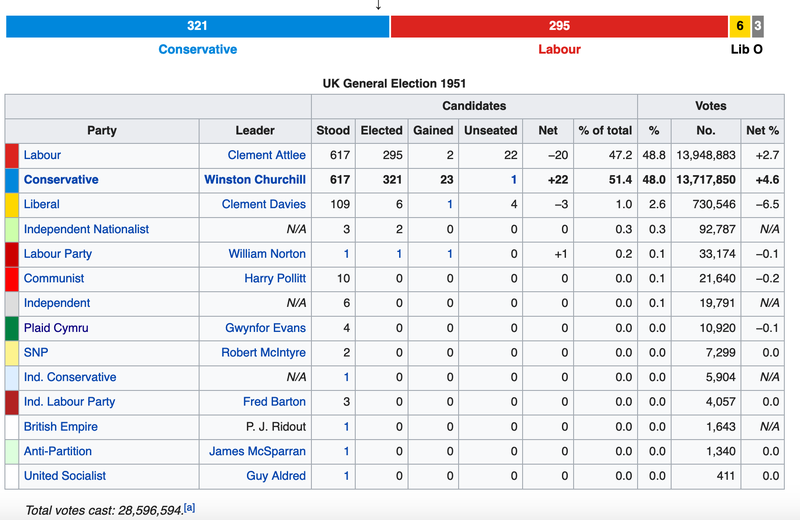

In 1951 Labour won the popular vote with the largest vote share ever enjoyed by an incumbent government. The most radical government in our history was the most popular. If the Attlee administration had implemented proportional representation, as the Labour party had planned to do in the early 20th century, then it would have remained in office into the 1950s. The UK would in all likelihood have become by far the largest and most powerful of a Northern-European social-democratic bloc, along with the Scandinacian countries (in Sweden, for example, it was the parliamentary coalition between the Social Democratic Party and the centrist liberals during this period that laid the foundations for the long-term success of social democracy there). The future of Europe and the world would have been quite different. But, thanks to that fatal deference to British institutions that had already come to characterise the Labour Right, no serious attempts at constitutional reform were made by the Attlee government. Despite that government’s popularity after 6 years in office, First Past the Post worked to the advantage of the Tories, as it almost always does. They won the most seats. Labour was out of office for another 13 years.

In 1964 after an endemic Tory crisis, Wilson managed to scrape a tiny, ineffectual parliamentary majority. In 1966, at the very high water-mark of post-war social-democracy and trade-union power, he was able to call an opportunist election at a favourable point in the economic cycle, winning an impressive majority on 48% of the national vote. If any period stands as evidence against the theory that Labour can’t win elections on a progressive platform under First Past the Post, then it’s the 1960s. But even then, Wilson’s only convincing majority was won when he had the advantage of being in government and choosing the time of the election. And that was at the absolute historic high-point of social-democratic consensus, cultural radicalisation, working-class self-confidence and youthful baby-boomer optimism. The Labour-supporting Daily Mirror was the best-selling newspaper on the planet. Even a significant section of the ruling elite – at institutions like Oxbridge and the BBC – was sympathetic to socialism and Marxim because of their wartime experiences of the struggle against fascism. Anyone who thinks that we are now living through a remotely comparable moment is more optimistic than me.

Wilson lost the next election in 1970. He won in 1974, but only with a tiny majority, and having actually lost the popular vote. First Past the Post favoured Labour that year, but in doing so, it damned the party to 18 years in opposition, once it left office five years later. The party was only able to govern with the support of the Liberals after 1977, and found itself in charge of a socio-economic crisis that the most intelligent Tories all knew they had been lucky to escape having to manage. Labour’s reputation for economic competence took two decades to recover, and I would suggest that the collective political unconscious of the British working class has never really forgiven the party for agreeing to the 1975 IMF demand to start rolling back the post-war settlement, in return for a financial bail-out.

At the same time, changes to the nature and organisation of industry were undermining the traditional strongholds of Labourism already. Stuart Hall, Eric Hobsmawm and others tried to warn the left that the nature of the crisis and its outcomes would have serious repercussions for the viability of their traditional strategies. Some listened: but most called them traitors and sell-outs, only canonising figures like Hall in retrospect, many years later.

The trauma of the 1980s, including the 1981 formation of the ‘Social Democratic Party’ as a direct and damaging split from Labour, did not leave the party or the non-Tory left in any stronger position. Neither, of course, did the catastrophic defeats suffered by the workers’ movement on global and local scales during that decade. A completely failed project – a disaster for everyone who didn’t want to see the Tories in power for another 15 years – the creation of the SDP at least made it very clear that the British party system never was going to resolve itself into the simple two-party duopoly that Labour members always preferred to think of it as. This left Labour even more clearly unable to win parliamentary majorities without cooperation with other parties, and yet more unwilling than ever to pursue such cooperation, because doing so would mean making some kind of rapprochement with the traitors of the SDP (or at least with the party formed by their merger with the Liberals: the Liberal Democrats).

By the beginning of the 1990s, as a young Labour activist, I was convinced that Labour had only two strategic options open to it. It could preserve its identity as a radical socialist party of the organised working class and the public sector, probably thereby consolidating around 32% of the national vote, while conceding the ‘centre ground’ to the Lib Dems, allowing them to consolidate around 20%, while forming an alliance with them to produce a genuine anti-Tory majority (keep in mind that even in 1983, and certainly at all subsequent elections, the Liberal manifesto was far closer to Labour’s than to the Tories’). Or it could accept that the only way to win a majority under First Past the Post was to transform itself beyond all recognition, moving way further to the right that at any point in its history, so as to be able actually to take a significant share of votes directly from the Conservatives in Southern, middle-class constituencies.

At that time most of my fellow student activists, even on the far left, shared my enthusiasm for electoral reform. But they dismissed the rest of this analysis as far too pessimistic. They were certain that Labour could never move so far to the right as I was suggesting it might, and were sure that we would never have to work with the Lib Dems. They confidently looked forward to a future in which Labour governments, committed to radical democratic socialist programmes, would be elected under PR with over 50% of the popular vote. I often pointed out that this had never happened anywhere: even at the high point of Swedish social democratic hegemony. But for this, I was generally accused of defeatism.

Labour didn’t win again until 1997. The party won office as ‘New Labour’, effectively having conceded all real political power to its traditional enemies: outflanking the Liberal Democrats to the right, courting the votes of the aspirational middle classes at the expense of almost everyone else, openly conceding a veto over its programme to Murdoch and the City of London.

This sounds like a condemnation, and it partly is. But it is crucial to be realistic and objective about the conditions under which Blair and his colleagues operated. They were fully aware of the history that I have laid out here, and its implications. They were working under conditions of peak neoliberal hegemony. There had been no major crisis for neoliberalism, no upsurge of countervailing forces, no significant generational swing to the left (although since 1990, the Tories’ traditional poll lead among women had collapsed among younger voters, and that tendency would continue to this day). Most of the residual Bennite wing of the party continued to behave as if global neoliberal hegemony were the fault of the perfidy and cowardice of Neil Kinnock (who had led the party from the left to the right between 1983 and 1992), and that it could somehow have been magically reversed if only he had stood firmer on socialist principles. They offered no realistic strategic solutions to the worldwide crisis of the left. It is true that, for example, if John Smith (Labour leader 1992-4) had lived then he probably would have won the 1997 election (by a much smaller margin than Blair did) and enacted a somewhat more radical programme than Blair: but he would have been destroyed by the press for doing so, and pushed out of office after one term.

Under these conditions, the only logical thing for Labour to do was to pursue a policy regime that explored what redistributive, democratic and socially-liberal policy options might be open to it, while accepting that the power of Murdoch and the City could never be challenged. Of course I condemned them at the time, as did my intellectual hero Stuart Hall. But in retrospect it was never clear what assemblage of social forces we expected them to mobilise in the fight against the triumphant capitalist class: just 7 years after the collapse of the USSR.

Blair, like the British electorate (I think), showed an intuitive genius for registering the real balance of forces in a given social formation. He (like they) knew that there was no point in a political party or movement making promises that its current level of strength left it in no position to keep. Where he stands condemned, by my analysis, is in the complete lack of interest he showed throughout his time in office in doing anything at all to change that balance of forces. I honestly think that any Labour government elected in 1997 – that wasn’t planning a one-term kamikaze mission against the legacy of Thatcher – would have had to implement pretty much the same programme that Blair did initially, to avoid finance capital and its political agents simply annihilating them. The alternative would have been to introduce PR and form an alliance with the Liberal Democrats: but die-hard Labourists like John Prescott threatened to resign from cabinet if any such course were pursued.

Nonetheless, over the next two parliamentary terms all kinds of things could have been done to change the situation. An aggressive programme to raise union density, a serious plan to restore the power and dignity of local government, and a genuine effort to improve and strengthen our independent media sector: all of that could have been done and should have been. And if it had, then Labour in office might have been able to do the thing that it was not strong enough to do in 1997, but should have been strong enough to do by the early 2000s: to initiate some plan of industrial reconstruction in the North.

But in those days, the Tories were nowhere in the North and most of the Midlands. The swing voters that New Labour depended on were all aspirational middle-class citizens in the South. Labour lost literally millions of votes in the ‘heartlands’ between 1997 and 2010: by far the greatest proportion of those that have been lost since that time. The road to 2019 was built by New Labour during this time.

Of course this was, fundamentally, because Blair and his colleagues had made an alliance with sections of the capitalist class – the City, the media owners – who had no interest in seeing British national manufacturing recover. But it was also because they were under no electoral pressure to change course, because the votes of former miners counted for nothing under First Past the Post. According to some reports, Blair was cognisant of all this history and wanted to implement PR, as recommended in 1998 by the commission that he had set up the previous year; but he was blocked by figures in his own cabinet such as Prescott and Jack Straw, allied to the most reactionary sections of the traditional Labour Right. However, the head of the commission, Roy Jenkins, thought that Blair himself was the ultimate obstacle to reform. Either way, without any obvious political motive to do so, faced with internal opposition and challenging external circumstances, Blair neither pushed forward with democratic reform, nor pursued any political course that would have prevented the alienation of its ‘traditional working class voters’ from the Labour party.

Of course, Blair’s failure to pursue a policy programme that would actually have reversed the rise of inequality in the UK (rather than just slowing it down), would have actually begun to restore the power of organised labour (rather than just offering workers some minimal, if significant legal protections), would have broken the stranglehold of Murdoch and his kind over our culture: none of this was primarily down to issues of electoral politics or system. Under the historic conditions that they were working under, the New Labour government achieved a great deal: restoring funding to core services and effecting impressive levels of regeneration in many poor urban areas. Their limits were the limits of the coalition of social forces that they had built: the Labour party and its institutions, a largely passive membership and electorate, sections of the ruling class committed to a project of social liberalism and cultural modernisation. If anyone else had been able to build a better one, then they could have had a go: but they (we) didn’t.

Once Labour finally hit a real economic crisis, under Gordon Brown, 2008-10, there was no assemblage of social forces with which to resist the Tory resurgence. After the 2010 election, the Liberal Democrats – having been denied the electoral reform that Blair had promised them for over a decade – threw in their lot with Cameron, who had won more votes and seats in parliament than Brown. Of course, Cameron had come nowhere close to winning a majority of actual votes in the country, and the 2010 Labour and Lib Dem manifestos were (as always) much closer to each other than to the Conservatives’. Under PR, a Labour-Lib Dem coalition would have been the probable outcome, and university tuition fees would never have been raised to £9k. Despite the fact that they were, we haven’t seen a Labour victory since.

Hard-Wired Tory Hegemony

Surely by now the lessons of all this history are plain. The failure to adopt a system of proportional representation – as used by almost every other parliamentary democracy in the world – has proven a consistent disaster for Labour and the people it represents. This is not because PR is some ‘magic bullet’ for promoting social democracy, but because it at least represents a significant democratic advance on First Past the Post: a system which used to be more common, a long time ago, but remains in operation now in Australia and Canada and almost nowhere else.

From a materialist perspective, this is not an insignificant issue. Social power relations, class relations, and inherent political biases can become crystallised into institutions and technologies in ways that make future outcomes and uses of them more or less likely. For example: there is nothing inherent in the core technologies powering smart phones that make it probable that they will be used to cultivate attention-deficit and neurotic, compulsive behaviours in entire populations. But our phones have been designed by institutions (giant capitalist corporations) that have every interest in them having that effect, and so certain tendencies for them to do so are built into the designs of interfaces, apps and platforms. In much the same way, First-Past-the-Post in Britain entrenches and helps to reproduce a set of power relations and political procedures which have always, only ever, benefitted the forces of reaction. That is one specific lesson of this story.

Of course it is also true that if we had had proportional representation for any significant portion of the past century, then neither the Labour party nor the Conservative party would still exist in anything like their present forms. Both would have fragmented into a number of smaller, more ideologically coherent units. I would submit that, given the history I have just outlined, whatever such outcomes may have ensued, they could hardly have been worse than the ones that we’ve endured.

But the more fundamental lesson is this. The forces of Tory hegemony are simply too powerful for Labour and its movement to overcome, without forming alliances with others, except at periods of unparallelled strength (or temporary crisis for the Conservative party). I’m afraid I do not believe that we are on the verge of such a period; nor is there is any chance of achieving one without a sustained period of reforming government laying the ground for it first. Of course such a recovery of strength would also require labour organisation, community mobilisation, and a general rebuilding of socialist culture. But it would also need at least some years of sympathetic government to gather momentum.

What would it take to fight back?

Let me be absolutely clear here. I am not about to suggest for a moment that simply reforming the UK electoral system, or collaborating with other political parties, would in any way be sufficient to the realisation of our political hopes. But I am going to insist that electoral reform is a necessary condition for achieving those objectives; and that it would be illogical to have accepted that the First Past the Post system is broken, and yet to insist on trying to win under that system while competing with other parties who also oppose it.

But first, if I am not suggesting that proportional representation – and electoral pacts to achieve it – constitute a sufficient means of defeating Tory hegemony, then what would?

On the basis of my analysis earlier in this series and here, I’d suggest that there are three principal domains in which working-class power and democratic efficacy have been deliberately and systematically undermined by 40 years of neoliberal hegemony. These are: labour organisation, local democracy and the media. In each of these fields, institutions that were sympathetic or conducive to the democratic, self-organised power of working people have been suppressed, diminished and defeated during the whole period since the 1960s. As I remarked already, I believe that it is the failure to intervene in these domains for which the New Labour administration will eventually be remembered most critically. Had they done more to regulate the press and support independent media, to actively encourage trade-union membership, and to restore power and autonomy to local government, then the Tory austerity assault could never have been as successful as it was.

Each of these is a front on which we must now fight: organising communities and demanding local reforms, while building a local sense of solidarity and possibility; supporting our own left media while openly attacking the right-wing bias of the existing outlets; above all, working to rebuild our unions by any means necessary must be seen as an urgent task for all of us. Each of these is also a major area of reform to which any future Labour or Labour-led government must commit.

And yet we will not achieve such a government without taking the weakness of our electoral position seriously. The 2019 election made one thing very clear. Half a million new members, a new culture of technologically-enabled mobilisation, and a commitment to radical socialism, were able to save Labour in England and Wales from the kind of collapse that it suffered in 1983 and that so many of its counterparts have already suffered elsewhere (including, lets not forget, in Scotland). But it was not, and was never going to be enough to overcome a political system that overwhelmingly advantages the Conservatives, once the Tories had lined up behind a coherent new hegemonic strategy.

Labour cannot overcome these forces alone, short of a miraculous and literally unprecedented recovery of its historic strength, past anything that it has known before. It will only overcome them if it can lead a bloc of democratic forces that will include activists, community groups, unions, and other organisations all round the country. There is no getting away from the fact that it will have to include other parties: all of those parties, including the Liberal Democrats, who do not benefit from the right-wing bias of the British press and the British state. This anti-Tory coalition will have to be understood, at a certain level, as an alliance of different social groups and different class fractions all of whom share a common interest in preventing the destruction of life on Earth. But yes, it will also have to take the form of political co-operation between groups and parties that are used to competing with each other.

I say it will ‘have to’ because I simply do not think that Labour alone is institutionally capable of mobilising the levels of support that would be required to overcome the obstacles that we face. Does anyone really believe it is? What would it even look like if it were? Perhaps if Labour party membership could actually pass the 1 million mark, then it may become plausible to suggest that the Labour party alone can contain and cohere the entirety of the movement that we need. Until that happens, we must try to begin to take seriously the reality of our strategic situation.

“an alliance of different social groups and different class fractions all of whom share a common interest in preventing the destruction of life on Earth”

We will lead, or we will die

Early in 2017, I argued strongly for a strategy of cooperation with other parties. I suggested that we should pursue deals with other non-Tory parties according to which we would stand down for each other in specific seats that each party respectively could not win, on a quid-pro-quo basis, and only in seats in which local parties were happy with the arrangement. The aim would be to win a non-Tory majority, which would then introduce PR immediately (presumably what would be introduced would be the system recommended by Jenkins in 1998). Another election could then be held under PR, or seats could be allocated under the new system according to the vote at that election.

The proposal was not necessarily for any formal alliance with other parties beyond that. It must be stressed that this was never a proposal for Labour to ‘stand aside’ for other parties except in cases where a) the local party had deemed the seat unwinnable by Labour and b) the other party in question had agreed to stand aside for us in at least one other comparable constituency, allowing us to win it. The result of any such arrangement would only ever be a significant net gain of seats for Labour and a greater net loss for the Conservatives. It must also be stressed that neither I, nor any advocate of such a scheme, has ever suggested that Labour or its supporters would stop engaging in movement-building and socialist proselytising in constituencies where Labour did not happen to be fighting specific elections. And of course, the proposal was never for Labour to offer significant concessions to other parties on matters of core concern to our base in return for such cooperation. My assumption – and I think it is well founded – is that most small parties (including the Libeal Democrats) would make very few demands on a senior coalition partner who was offering them, finally, proportional representation.

Beyond this, I do, in fact, think that we could propose an alliance with other parties – even Liberal Democrats – that went further than mere electoral-reformist expediency, on the grounds that the current climate crisis and the long-term crisis of British democracy and society are demonstrable and urgent realities, that would obviously require a great collaborative effort by different social groups to address. We could invite all parties, and members of none, to join us in the task of forging a Green New Deal.

What the effect of making such a public invitation would be, I don’t know. Some parties might accept it, some might reject it, some might split over it. I do know that we would have nothing to lose by trying, and there would be nothing forcing us to continue with any such arrangement were the outcomes not ones that we were happy with.

What is deeply disturbing is the frequent insistence of so many leftists that even trying to initiate such a process would constitute some kind of betrayal (of what – socialism? the working class? – is never clear). This is not a rational response to a political and ecological crisis. It is a symptom of psychic investment in a dogmatic and dangerous fantasy: the fantasy of one People, one Party, one Leader expressing all the truth and virtue in the world. And to make the Labour party – of all things – with its compromised and complex history, the object of such as fantasy: it’s frankly incredible.

My report was published a few months before the 2017 general election. Our electoral result in June of that year was much better than I had dared to hope for when I wrote it. But we didn’t win. If my suggestions had been followed (and I know that they were discussed by some close to the party leadership), with electoral deals being done over merely a handful of seats across England, then we would have ended up with a Corbyn-led government. As it was, the first-past-the-post system allowed Theresa May to stay in office that year, despite Labour’s achievements and her evident unpopularity. As for 2019: I’ve made very clear in this series why I think that that election confirms even more strongly the argument that I made in the January 2017 report: that Labour can’t win on a radical platform on its own, under First Past the Post. At least, not short of a miracle.

But We Came So Close in 2017 – Didn’t We?

Of course, critics of this perspective might look back to the near-win of 2017 and suggest that we might be able to reach that point again, and even cross the line this time, if we’re not hampered by the Brexit conundrum, and if we have slightly more effective leadership and narrative. Well it’s true, we might. But I have several responses to make to this.

One is to refer to my analysis in part four of this series, on Brexit. I would suggest, on the basis of the evidence there, that Labour simply will not be able to put together that full electoral coalition again without adopting a reactionary position on immigration, or without having finally won a decisive ideological victory against right-wing nationalism. I know how hard this is for many of us to take. But the clear fact is that one of the conditions for the 2017 result was our manifesto commitment that free movement would end with Brexit; and the membership will, rightly, never allow us to take that position again.

So to achieve a result like that, we would have to have made significant gains in an ideological war against Murdoch and his ilk. And granted, the latter objective is hypothetically plausible. I’ve said we should strive for it, and we should. But if we’re going to launch an ideological campaign against right-wing nationalism, why on Earth wouldn’t we try to enlist the liberals into it, given that favouring a liberal immigration policy would be one of the few positions that almost all Labour radicals would share with almost all Liberal Democrats? Just because we hate them forever? Is that really grown-up politics?

Another argument is simply this: why not? Even if we were in a position of unusual strength, making it possible to win an election alone, wouldn’t any principled democrat among us want to see proportional representation introduced anyway, purely for democratic reasons, and given all the evident harm that First Past the Post has done us? And in that case, why not at least do a one-off electoral deal just to ensure that it would happen, and insure against any unforeseen disasters? What exactly would we lose by it? Even if we had managed to squeeze the Lib Dem vote even more than in 2017: the very fact that we had done so would surely demonstrate that we had nothing to fear from allowing them the representation in parliament that democratic justice demands.

But finally, the most powerful argument in favour of such a strategy is simply this. Like any historical moment, ours is constituted by complex and contradictory tendencies. On the one hand, as I have explained, it is shaped by the long-term effects of noliberal hegemony and by the shorter-term effects of its recent crisis. It is newly dominated by the resurgence of reactionary nationalism, adapted to the era of platform media culture. But is is also shaped by the very tendencies of which Corbynism was just one, early and (hopefully) immature expression.

Those tendencies are manifest in the recent re-emergence of many of the political demands that neoliberalism was brought into existence to contain: demands for forms of equality that could not be delivered by post-war social democracy (predicated as it was on patriarchy and white supremacy); demands for democracy in the home, the workplace, the community and the school. They were already present in the short-term eruptions of radical democratic utopianism that characterised the anticapitalist movement of the early 2000s, and Occupy a few years later. They are present in the half-formed, confused but authentic critique of representative democracy that informs Extinction Rebellion.

These are the forces that can animate a 21st-century socialism, appropriate to the age of networked communications and complex social identities. But nobody can seriously argue that such a politics can be contained and owned by one dogmatic party, committed to a mid-20th century model of social change. Labour must let go of the ideology of ‘Labourism’ because it is wholly inimical to the complex culture that a contemporary socialism must embrace. This is true at the most general level. But it is also clearly true at the specific level of British electoral politics.

We inhabit a political system that is not only designed to prevent the socialist left of the Labour party from taking power. It is now clearly biased against every force other than nativist ‘platform nationalism’: ‘disaster nationalism’ in the age of ‘platform politics’. Under such circumstances, it makes no sense not to try to build as broad a coalition of anti-Tory forces as possible – from anarcho-communists to liberals – to try to challenge its and change it.

Would this be easy? Of course not. But life is hard. It is likely that the displaced political class, and their liberal supporters in the wider managerial class, will make at least one more attempt to regroup and take back the control of anti-Tory forces that they enjoyed throughout the New Labour period. The Labour leadership election is the most obvious opportunity for them to do so. If the winner is a soft-left figure like Starmer, then they will exert immense pressure on him to capitulate to their authority and their agenda. If it is someone from the left: well, we already know what they will do. Either way, such pressure must be resisted at every turn.

But it must not be resisted merely with a view to isolating and separating Labour’s existing coalition from the middle-class liberals. As our psephological analysis has made clear: it was losing their support that cost Labour perhaps more dearly between 2017 and 2019 than anything else. We may have to show them once again that the long 1990s is over, and that the coalition to defeat the right can now only be led from the left. But we must bring them into that coalition, whether that means bringing them into our voting bloc or not: if we can’t, then we are done for.

This is a proposition that meets with endless resistance from the romantic and dogmatic left, who see any talk of cooperation with liberals and centrists as necessarily some form of betrayal, and who recognise no greater virtue than that of inflexibility.

Well, we have been here before. In the 1930s and 1940s, faced with the emergency of fascism, the communist and socialist lefts had to overcome similar qualms and dogmatism in order to fulfil their historic duty. From the New Deal administration to the post-war Labour government; in Spain, in France, and on a continental scale, when the Red Army became the only obstacle to the military triumph of Nazism: some were defeated, others were victorious, but no other strategy could have worked. The forces of the left led the coalitions that the liberals were obliged to join. That is how fascism was beaten, and how the gains of the post-war settlement were made possible. In the new form of reactionary, anti-democratic politics that Johnson represents, and in the climate crisis that threatens the viability of life on Earth, we face no less of an emergency now. We will lead, or we will die.

Read the rest of Jeremy Gilbert's series:

part 1: It was the centrist dads who lost it

part 2: Corbyn was intensely moral, but never a working class hero

part 3: Labour should have argued against the last 40 years, not just the last ten

part 4: Labour let the right shape both sides of the Brexit debate

part 5: To take on the right wing media, we need to build a political movement

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.