Jane Austen may have satirised the gothic novel in Northanger Abbey, but a letter to be auctioned for the first time next week shows her enjoying the guilty pleasure of such sensational fiction herself.

The letter, dated 29-30 October 1812, was sent to one of Austen’s favourite nieces, Anna Lefroy. It is written as a note to the author Rachel Hunter, whose 1806 novel Lady Maclairn, the Victim of Villany the two had recently read.

Austen mercilessly parodies Hunter’s melodramatic style, and praises cliches and flaws found in the novel such as the heroine’s relentless tears, the dismal setting and repetitions of plot and character.

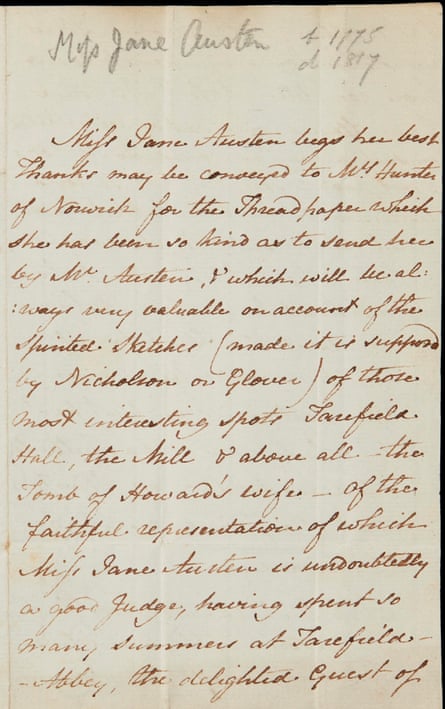

“Miss Jane Austen begs her best thanks may be conveyed to Mrs Hunter of Norwich,” the letter begins, before going on to thank Hunter for sketches of locations in the novel that Lefroy had already sent to Austen as part of their long correspondence.

As tart as a putdown from Elizabeth Bennet, Austen draws humour from Hunter’s overblown prose, declaring at one point that “tears have flowed over each sweet sketch”. The reader is left in no doubt that any tears shed were of laughter and not despair.

Gabriel Heaton, Sotheby’s specialist in books and manuscripts, declared the letter a significant document. “Although the content was known,” he said, “the letter itself has not been seen by scholars and it is very exciting to have it become available”.

It is expected to be the star performer of three lots being offered by the auctioneers for sale by descendants of Austen’s family on 11 July 2017. Alongside two other fragments of correspondence between the two women, the lots are expected to sell for as much as £162,000.

Though clearly written for comic effect, Heaton said what had struck him about the letter was how Austen imagined herself in the world portrayed in Hunter’s novel. “It is similar to how she wrote about her own novels,” he suggested, “talking about what happened to characters as if they were in the real world”.

Her gleeful spoofing of Hunter’s work was, he said, reminiscent of Northanger Abbey, which was completed in 1803 but only published after Austen’s death. In it, Austen turned her critical eye to the conventions of a genre whose bosom-heaving antics soared in popularity among young women as the 18th century drew to a close, thanks to writers such as Matthew Gregory Lewis and Ann Radcliffe.

The letter indicates that Austen was perhaps not as disdainful of the genre as Northanger Abbey suggests, as she was still reading such fiction almost a decade after completing her parody. Heaton likened Austen’s enjoyment of gothic novels to the contemporary love of lowbrow box sets. “She is talking to a friend and showing how she is enjoying trash, which is how a lot of people saw the novel at the time, not just gothic novels,” he said. “Jane was a great defender of the artistic integrity of the novel, but not necessarily all novels.”

The text of the letter has only previously been available through four 19th-century copies, which include mistakes and additions. It offers insight into Austen’s engagement with contemporary writers at a crucial stage of her writing life. Her first novel, Sense and Sensibility, was published the year before, while the manuscript for Pride and Prejudice had just landed on her publisher’s desk.

Janet Todd, who edited Austen’s complete works for Cambridge University Press, said the letter was typical of the writer. “Austen hugely enjoyed ridiculing other women writers and their improbable, sentimental and gothic plots,” Todd said. “She knew well her own literary powers – and probably learned a good deal of what not to do by reading the interminable romances and effusions of contemporary authors.”

Todd added that she was looking forward to seeing the original letter in Austen’s hand. “Austen has becomes such a cultural figure in Britain and so much part of the heritage industry that I hope that it stays in the UK – preferably at Chawton cottage.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion