Conservationists are all around us, forever appearing on our televisions with their pleas for this noble, endangered mountain lion or that cute, imperilled subspecies of vole. But 70-year-old Edward Allhusen is one of a slightly different stripe. Instead of trying to prevent creepy-crawlies going extinct, he is trying to save the lives of words. In a new book, Betrumped: The Surprising History of 3,000 Long-Lost, Exotic and Endangered Words, he has included a sort of highly endangered list of 600 vocabulary items, culled according to no more systematic criterion than personal preference, from Johnson’s Dictionary of 1755.

“Due to lack of care by us, the users, many of these words have slipped away into obscurity,” he says, poignantly. “Here, in this retirement home of language once inhabited by Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde, these gems of the English language will soon be forgotten unless we make an effort to use them at least once a day. Otherwise, they could become extinct within a generation.”

Among these words are such corkers as juggins, fizgig, hobbledehoy and condiddle. Also on the way out, as reported, are words I thought were still relatively well understood, among them defenestrate, caterwaul, crapulence, amanuensis, pettifogging, trollop, vamoose, lickspittle and conk.

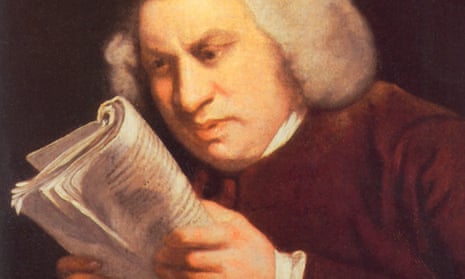

Sympathise with him though many of us no doubt will – who doesn’t love a fizgig? – there seem to me to be both theoretical and practical difficulties with his project. The theoretical difficulties were outlined by none other than Dr Johnson himself in the introduction to his dictionary: “When we see men grow old and die at a certain time one after another, from century to century, we laugh at the elixir that promises to prolong life to a thousand years; and with equal justice may the lexicographer be derided, who being able to produce no example of a nation that has preserved their words and phrases from mutability, shall imagine that his dictionary can embalm his language, and secure it from corruption and decay, that it is in his power to change sublunary nature, or clear the world at once from folly, vanity, and affectation.

“With this hope, however, academies have been instituted, to guard the avenues of their languages, to retain fugitives, and repulse intruders; but their vigilance and activity have hitherto been vain; sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride, unwilling to measure its desires by its strength. The French language has visibly changed under the inspection of the academy; the stile of Amelot’s translation of father Paul is observed by Le Courayer to be un peu passé; and no Italian will maintain, that the diction of any modern writer is not perceptibly different from that of Boccace, Machiavel, or, Caro.”

Language, in other words, changes all the time and there’s nothing much we can do about it. Words are as mortal as you and me. You might as well try to lash the wind, as Johnson said – and which most of us will sing in our heads in the voice of Donovan. Indeed, linguistic change – the amazing porousness of English to influence, its macaronic glory – is exactly what gave us all these interesting words in the first place: Allhusen boasts of finding roots for his 3,000-strong canon in more than 100 languages. Nor is linguistic change simply an additive process. It involves what the economist Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction”; old words change meanings or make way for new ones.

So for the practical difficulties, most of these words have vanished or are vanishing from our language because they have either been superseded by other words for the same things – or because the things they describe have ceased to exist or gone out of fashion. Who now keeps an amanuensis? If you offer to show your tarse to even the most biddable trollop these days it won’t go well for you. And if we’re to use defenestrate, as Allhusen suggests, “at least once a day”, we’re going to have to start throwing a lot more stuff out of windows – which is not nice and raises health and safety issues.

All this is at the heart of the absurdity of the sort of people who turn purple when they hear on the news that a city has been “decimated by mortar fire”. Can this ignorant newsreader, they scoff, intend to mean that one man in 10 of a Roman legion has been put to death as a collective punishment? No, of course, the newsreader does not mean that. Decimated has been repurposed to mean “wiped out” because there isn’t much of a call for words to describe the mass killing of Roman legionaries these days. Some will think this a good thing.

Likewise, another bugbear of self-styled pedants, enormity. It means moral wickedness, they shriek: not enormousness. But, as Oliver Kamm points out in his book Accidence Will Happen: The Non-Pedantic Guide To English Usage, enormousness meant moral wickedness before it meant enormousness, so where does that leave us?

Caterwauling, I expect.