Colorado’s Longs Peak: A cathedral of possibility

Dawn broke high in the Colorado Rockies, the enormous blot on the horizon revealing itself slowly, regally against an indigo sky.

I dropped my pack on the frozen tundra, overcome by awe and a taut, primal fear.

Before me stood cathedral upon cathedral of stone, a mysterious citadel crisscrossed by narrow ledges and vertical walls lashed by fierce winds.

This was the sheer eastern face of Longs Peak, a 14,259-foot fortress of rock that had recently killed three climbers and has sent hundreds more scurrying in retreat.

The entrance — the Keyhole — was there, atop a tower of boulders. The massive natural stone gate was a portal to another world, a world of wind and light or, for the unlucky, a doorway to oblivion.

Make no mistake, this was no Mt. Everest and I no SirEdmund Hillary. But given the events of the previous months, it might as well have been.

In October 2009, I was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer of the tonsil. I figured I’d have a tonsillectomy, eat some ice cream and get on with my life. But it wasn’t that easy; in fact, it was deadly serious. For the next six months, I endured intensive chemotherapy and radiation treatment that left me unable to speak, swallow or eat. I fed myself through a stomach tube, dropping more than 20 pounds. I lost my sense of taste, and my arms and legs turned to matchsticks.

Toward the end of my treatment, I was unexpectedly offered a job in Denver. Cancer had altered my perspective on the world and my own vulnerabilities. Newspapers, where I had toiled for 24 years, were in a tailspin. I figured the likelihood of getting insurance if I were laid off was pretty much impossible because of my preexisting condition. So I took the job and moved my family to Colorado.

I was hardly new to hiking and climbing, having spent the better part of the previous 14 years roaming the mountains and deserts of California. But I wasn’t that person anymore. I was weak. My forays around Boulder, Colo., left me embarrassingly winded.

Worst of all was the prison of fear I had built for myself — the fear of cancer returning. It crept up beside me when I was enjoying a moment with my son or daughter to whisper dark threats in my ear — “Don’t get too comfortable. I’ll be back.”

As I battled feebleness and fear, I became fixated on Longs Peak. Everywhere I looked, there it was, sitting hugely, imperiously, on the horizon, practically screaming, “I am!”

Distinguished by its enormous girth, wave-like profile and oddly flat top, Longs is the 15th-highest mountain in Colorado, the highest in Rocky Mountain National Park and one of the most popular hikes in the state. Each year, thousands try to scale this monster, forgetting that just because it’s popular doesn’t mean it’s safe.

The fastest winds ever clocked in Colorado — 201 mph — were measured in 1981 atop Longs. Climbers have been flung from the summit and swatted from ledges. Others have suffered heart attacks on the ascent. Only three of every 10 hikers ever reach the top.

Common sense said it was too soon to take on this giant. My hands and feet were still numb from the chemo. I had a catheter in my chest. High doses of radiation had left me unable to taste food, so I remained gaunt.

Yet an idea took hold that I couldn’t shake: If I could climb Longs Peak just a few months out of treatment, surely I had beaten this awful curse. The mountain would heal me, restore my strength, give me a second chance.

It was a dumb idea, but I excelled at dumb ideas. So a week after Labor Day 2010, I made my move.

I set off at 2:30 a.m. so I could get off the summit before the afternoon thunderstorms and killer lightning rolled in.

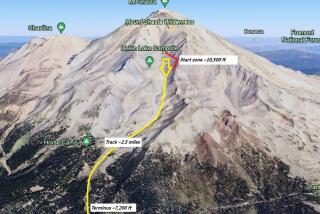

The 16-mile round trip would be done in stages: the Boulder Field, the Keyhole, the Ledges, the Trough, the Narrows and the Home Stretch.

I strapped on a small headlamp and headed into a dark forest. I hoped to experience some Zen-like oneness with the woods. Instead, I kept hearing what sounded like mountain lions, foraging bears and ill-tempered moose stalking me in the night.

As I emerged above the tree line, a tilted wooden sign pointed the way to the Boulder Field.

With the quiet forest now behind, the wind picked up and grew to a roar in my ears. The scenery was alien, full of frozen bogs and tall, oblong stones lurking in the blackness. More than any other landscape, mountains seem most alive. There is a presence, a watcher remaining just out of sight. Anyone who roams the world’s high places has felt it.

As dawn broke, Longs began to glow.

The Keyhole, bathed in rich orange, beckoned. A group of hikers trudged past me in defeat, beaten back by high winds.

They were younger and clad in the best gear, unlike me and my four layers of sweaters and my daughter’s pink book bag crammed with dates and pretzels. As I began rethinking this adventure, a flicker of light caught my eye — a tiny headlamp on the summit. Someone was up there! My heart soared.

I leapfrogged over the rocks to the Keyhole and looked through. It was another world, a magnificent moonscape of rocky spires, plunging gorges and glacial lakes. And it went straight down. There was no trail here — only painted bull’s-eyes along precarious ledges. Two hikers cowered beside me. We didn’t speak, but the question was obvious. Who would go first?

Without thinking, I flung myself through the Keyhole.

Seconds later, I hugged the mountain for dear life, absorbing blast after blast of wind.

I picked my way across the ledges, following each bull’s-eye. After a quarter mile, I reached a 600-foot, near-vertical wall — the Trough — the toughest part of the climb. And it was a climb now, not a hike.

I was at more than 13,300 feet, and breathing became more difficult. After every few steps, I stopped to suck air. The bravado that propelled me through the Keyhole evaporated, replaced by a brief wave of nausea. The Trough seemed insurmountable, and I wondered whether my attempt would end here. I took it literally inches at a time, and after nearly an hour I worked around a hanging precipice and was on top of it.

Yet there was no time to rest. The Narrows, a thin indentation along the backside of Longs, was right there. Parts were as wide as a sidewalk, others as skinny as a footpath, skirting thousand-foot drops. I walked along, keeping one hand on the wall while marveling at the ghostly spires of rock looming before me.

Where the Narrows ended the Home Stretch began. It was a tower of smooth white stone that seemed nearly vertical. I was careful to stay in a narrow groove to the left to avoid being stranded on an exposed 300-foot-high wall.

With the end now in sight, I ascended methodically, painfully toward the top. I saw the summit marker a few feet away.

After nearly seven hours, I flopped over the last boulder and was on the top, a flat 300-yard expanse of rock easily seen from downtown Denver 60 miles away and the eastern plains far beyond. Everywhere, mountains rippled forth like a great frozen sea.

I stumbled around in the sun, drunk on endorphins.

Climbers hauled themselves up, shaky and giddy.

Everyone had a story.

“I drove 19 hours straight from Indianapolis to do this,” said a beaming 29-year-old Jesse Housen. “This has been in my mind for the last two years. It was very rough. I’m dizzy and nauseous, but it was all worth it.”

I drank in the intense vibe and laughed at my foolishness. I had climbed this mountain thinking it would represent some triumph over disease, that it would herald the return of my strength and maybe turn back the clock on the last few months.

But I knew now that I could never go back and I didn’t have to. Chemotherapy and radiation are harder than any hike, cancer scarier than any mountain.

I felt vigorous and still part of the great feast of life. For months, I had embraced fear, mistaking it for vigilance. But fear is fleeting; it can live only if we cling to it.

At that moment I let it go.

Clouds gathered, and I knew it was time to leave. I felt as light as air, like I could fly off that mountain and glide all the way home.

I looked over the edge and contemplated the journey ahead.

Whatever the future held, I had climbed my mountain long ago and it was all downhill from here.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.