Inside Colin Powell's Decision to Declare Genocide in Darfur

In September 2004, then-U.S. Secretary of State, Colin Powell, became the first member of any U.S. administration to apply the label "genocide" to an ongoing conflict.* Interviews I conducted for Fighting for Darfur: Public Action and the Struggle to Stop Genocide revealed that despite a thorough investigation into the atrocities in Sudan's western region of Darfur, the legal advice given to Powell was that the resulting evidence (on which he based his genocide determination) was inconclusive. Now a newly declassified State Department memorandum sheds further light on why Powell nonetheless decided to label the situation in Darfur genocide.

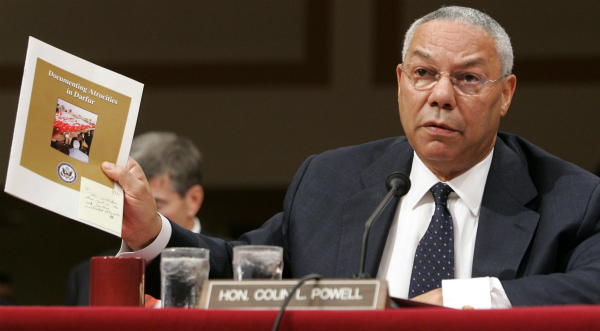

Sitting before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on September 9, 2004, Secretary of State, Colin Powell, was taking his time getting to the question that everyone in attendance was waiting for him to answer. "And finally" he said, "there is the matter of whether or not what is happening in Darfur is genocide."

The U.S. House and the Senate had drawn their own conclusion on the question some six weeks earlier. Through a concurrent resolution, Congress had determined that atrocities being committed against non-Arab groups by the Sudanese government and their proxy militia force in Sudan's western region of Darfur did indeed constitute genocide. It was not the first time Congress had accused the Sudanese government of genocide. They had drawn the same conclusion back in 1999 with respect to the Sudanese government's actions during a brutal war in southern Sudan that resulted in the deaths of an estimated 2 million people. But if Powell were to make a determination of genocide in Darfur it would be unprecedented: the first time the executive branch had used the word "genocide" in relation to an ongoing conflict.

"When we reviewed the evidence compiled by our team, along with other information available to the State Department, we concluded that genocide has been committed in Darfur and that the Government of Sudan and the jinjaweid bear responsibility -- and genocide may still be occurring" said Powell.

Up until that moment, Powell had been studiously avoiding a growing chorus of reporters' questions about whether Darfur was genocide. He had been awaiting the results of an investigation that his staff had hoped would provide "clear evidence" of whether or not the label was applicable. It had turned out to be a false hope.

Investigating Genocide

The State Department investigation, which involved the deployment of 24 independent experts to the Chadian border where refugees of the atrocities were fleeing, had primarily been the brainchild of assistant secretary Lorne Craner. And like so much of the State Department's thinking on Darfur over this period, it was influenced by the massacres in Rwanda a decade earlier.

Craner remembers Powell saying: "There is not going to be another Rwanda." (Powell has no recollection of this. "It wasn't that I wasn't mindful of Rwanda of course, I just don't recall making that statement" he says.)

Craner says he knew exactly what Powell meant, having finished the Pulitzer Prize-winning book A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. The book, written by former journalist and now Obama adviser, Samantha Power, memorably recounted how the Clinton administration had tied itself in semantic knots to avoid using the word genocide while the 1994 massacres of over 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu were underway in Rwanda.

The ban on saying "genocide" by the Clinton administration arose out of a briefing compiled by the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Inside the May 1994 briefing (later declassified by the National Security Archives), State Department lawyers said they were worried that a finding of genocide might obligate the administration "to actually 'do something.'"

The concerns of the State Department lawyers stemmed from the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, which was drafted in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Article I of the convention places an obligation on those who have joined, like the U.S., to "undertake to prevent and to punish" genocide. The article does not elaborate on what the obligation means in practical terms, and certainly does not specify a requirement for the deployment of troops. But in the wake of the Clinton administration's Black Hawk Down disaster in Somalia, there was no desire to even open a discussion about the engagement of U.S. resources in another African country. So, despite clear evidence to the contrary, U.S. officials refused to label the Rwandan atrocities genocide.

Craner viewed the U.S. government's avoidance of "the g-word" with shame, and committed not to repeat such a failure if he encountered an analogous situation.

So in March 2004, as the Darfur atrocities belatedly captured mainstream media attention, Craner decided to start building internal support for an investigation to determine if it was a situation of genocide.

Five months later, the investigation report arrived on Powell's desk. At a meeting to discuss the results, all eyes were on Powell's legal adviser, William Taft IV, who was tasked with answering the question that had motivated the ambitious research endeavor: Were the atrocities in Darfur genocide?

"We can justify it one way, or we can justify it the other" Taft said.

The "Specific Intent" Challenge

The U.S. government's historical refusal to label atrocities genocide while they are occurring has often been politically motivated; avoiding the word has been a way of avoiding the imperative to act in response to what many consider the world's worst crime. But there is also a legalistic reason the term has rarely been invoked in the midst of the crisis. The key feature of genocide is something called "specific intent" - meaning that the atrocities are carried out with the intent to destroy all or part of the victim group.

Absent public statements of intent to destroy the group - something most génocidaires are savvy enough to avoid - specific intent is something that has to be inferred from events on the ground. And with external investigators typically shut out during the worst of the violence it is often hard to gather enough evidence to draw this inference conclusively until the genocide is over.

Some cases stand in exception to this rule, including Rwanda where the contemporaneous indications of intent were overwhelming. Usually the best time to reach a legally watertight genocide determination has been in a courtroom after the crime has occurred. But that of course emasculates the moral power of the word genocide to build the pressure to stop atrocities in real time, which is exactly why Craner was keen to see if a genocide determination could be made sooner rather than later.

According to Taft, there was no doubt that the refugee accounts of mass killings, rapes, and destruction of items needed to sustain life for Darfur's non-Arab population could all constitute the physical "acts of genocide." The challenge was whether they had enough evidence to also prove these acts were committed with the specific intent to destroy non-Arab groups such as the Fur, Zaghawa and Massaleit. Darfur fell into the category of situations where specific intent was tough to determine with certainty in real time.

As Powell recalls it "Will Taft told me that others could argue against the genocide determination with a strong legal basis, but that the conclusion on genocide was legally supportable."

In short, Powell says it came down to a "judgment call." And it turns out the call was Powell's alone to make.

Sole Decision Maker

Given the gravity of the issue, Powell's consultation with anyone outside the State Department was breathtakingly minimal. "There were no fights with the Pentagon. In fact I don't even remember having a conversation with the Pentagon about it," said Powell. According to then-Deputy National Security Adviser, Stephen Hadley, Powell came to see President Bush just two days before making his genocide determination. "I never asked the president, 'Do I have permission to do this?'" acknowledged Powell. "I just said that this is what I was going to do." Bush made no effort to stop him, and merely instructed National Security Adviser, Condoleezza Rice, to inform the heads of the other agencies "so they won't be surprised."

But what about the legal implications?

Was the Bush administration not worried about its legal obligations under the Genocide Convention like the Clinton administration was with Rwanda? Why, in the face of advice that the evidence was inconclusive, did Powell decide to tell the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that genocide had occurred? A recently declassified legal memorandum, written by Taft to Powell's deputy, helps explain.

The June 25 Memorandum

In the June 25, 2004 memorandum Taft wrote: "A determination that genocide has occurred in Darfur would have no legal - as opposed to moral, political, or policy - consequences for the United States." In the following paragraph, Taft explains that the U.S. State Department had rejected an "expansive reading of article I [of the Genocide Convention] that would impose a legal obligation on all Contracting Parties to take particular measures to 'prevent' genocide in areas outside their territory."

Legal scholars have often had differing views over what obligations do or do not flow from article I of the Genocide Convention. But the convention itself says that disputes over its interpretation or application should be brought before the International Court of Justice, and in the early 1990s, the court began to flesh out what the undertaking to prevent genocide meant.

In a 1993 case involving alleged atrocities underway in the former Yugoslavia, the court said that Article I put those who had joined the convention "under a clear obligation to do all in their power to prevent the commission of any such acts [of genocide]." Then in 2007, the court issued a judgment finding that Serbia had in fact violated those Article I obligations in the context of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide in which over 7,000 Bosnian Muslim boys and men were killed.

Careful to state that the legal obligation in article I did not require states to "succeed" in stopping genocide, the court concluded that a nation violated its article I obligation if it "manifestly failed to take all measures to prevent genocide which were within its power, and which might have contributed to preventing the genocide." Even though the court did not prescribe universally applicable measures -- since the measures required to prevent genocide will necessarily depend on the situation and the nations involved -- it clarified that the obligation may apply even when the genocide is taking place in another nation.

The U.S. is unlikely to ever face a judgment like Serbia received because in 1988, when the U.S. government belatedly ratified the Genocide Convention, it lodged something known as a reservation to protect itself from being brought before the court against its will for any alleged violation. Still, the court's interpretation of the genocide prevention obligation remains legally authoritative.

We will never know for sure, but had Taft's advice been that a determination of genocide would have obligated the U.S. to take all measures that might have contributed to preventing genocide then it seems improbable that Powell would have had such autonomy in making his genocide determination. And combined with Taft's position that the evidence was inconclusive, advice that a genocide determination would obligate the U.S. to act is likely to have led to the administration avoiding the word altogether.

Instead, with advice in hand that a genocide determination would be cost-free for the U.S. in legal terms, Powell's decision focused on what impact a genocide determination might have on other governments.

Strangely, Taft's June 25 memorandum states that Sudan is not a party to the Genocide Convention, although it had become so several months before the memorandum was written. As a result of this inaccuracy, Taft's advice does not dwell on what a genocide determination might mean inside Sudan itself. What he does conclude however, is that a finding of genocide in Darfur could "act as a spur to the international community to take immediate and forceful actions to respond to ongoing atrocities." Powell took this advice to heart, hoping that by using the word genocide he would move other nations on the UN Security Council to act.

There are more and less charitable ways of understanding Powell's decision: As a laudable and historic pushing of the boundaries in a genuine effort to stop genocide; as a misguided, or even self-serving, attempt to avoid the risk of a Rwanda-like shaming when the story of Darfur was eventually written; or as an endeavor to claim the moral high-ground in the midst of the war on terror that ultimately undermined the power of the genocide label. What is not in question is Powell's strategy of using the determination to spur other countries to act in Darfur failed.

Neither Taft's June 25 memorandum nor Powell himself factored in the legacy of the secretary of state's infamous 2003 testimony before the UN Security Council when he said Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. By the time Powell made his Darfur genocide determination, the U.S. invasion of Iraq had become a quagmire, global coverage of U.S. human rights abuses in Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo had diminished whatever "soft power" the U.S. had in the wake of 9/11, and Powell's personal credibility had been weakened by his WMD speech.

Far from spurring others to act on Darfur, Powell's genocide determination made other nations wary; his was perhaps the least credible voice of all to rally other states to the cause of human rights in a Muslim country. Not even the Bush administration's war-weary ally, Tony Blair, was willing to apply the genocide label.

What Powell's genocide determination did do, however, was to catalyze a U.S.-based citizens movement for Darfur. The so-called Save Darfur movement used the moral force of the genocide label to try to spur the U.S. government to action, believing that the battle to stop the atrocities in Darfur would be won or lost in the realm of U.S. domestic politics.

But seven years later neither a genocide determination by the U.S. government, nor an outcry by the American people have been enough to bring peace to Darfur.

Looking Forward

Genocide or not, the situation in Darfur today remains unresolved, with millions displaced and still too insecure to return to their homes. Moreover, a brutal war has now erupted in another part of Sudan, in an area called Southern Kordofan. It's no stretch to imagine that the State Department's current legal adviser, Harold Koh, will soon be pushed to answer the same questions as Taft faced seven years ago: Does the situation constitute genocide? And if so, what is the U.S. obligated to do about it?

The soundest response to the second question is that the U.S. is obligated to take all measures within its power that might contribute to preventing genocide. Moreover, according to the International Court of Justice, that obligation kicks in even in the absence of a conclusive genocide determination; those who have signed the convention are obligated to take preventative action as soon as there is a "serious risk" of genocide.

The response to the first question should be dictated solely by the evidence. But lining up the Clinton and Bush administration responses to Rwanda and Darfur respectively provides a telling reminder of how readily political ends, well-intentioned or not, can influence those tasked with deciding whether to label a situation genocide.

In the Clinton administration, the argument that a genocide determination would bring a legal obligation to act was used as a rationale for avoiding such a determination -- notwithstanding clear evidence that genocide was taking place. In the Bush administration, the argument that a genocide determination would not bring any legal obligation to act, coupled with an erroneous belief it might get others to do so, contributed to such a determination being made - notwithstanding legal advice that the contemporaneous evidence was inconclusive.

Though reaching different conclusions on whether or not to apply the genocide label, the decision of both Democratic and Republican administrations alike were influenced more by what they believed a genocide determination would mean in terms of action rather than by a strict interpretation of the evidence they had before them. The results to date suggest that neither Rwandans nor Sudanese have been well-served by such instrumentally-motivated avoidance, or use, of the g-word.

What lessons should be taken from this bleak history? One lesson is that it is time to revisit the assumption that whatever the U.S. government says (or does not say) is crucial to determining outcomes on the ground. Another is that it is unwise to place so much stock in a label -- even one as potent as genocide.

*It was not the first time a Secretary of State had uttered the word genocide in relation to an ongoing conflict. On June 10, towards the end of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, Secretary Warren Christopher, on a visit to Istanbul, responded to a question on whether Rwanda was genocide with the following answer: "If there is any particular magic in calling it genocide, I have no hesitancy in saying that." However, the same day, following Christopher's instructions that U.S. officials not use the word "genocide" directly, the State Department spokesperson continued to refuse to call the situation genocide. Powell's testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee therefore marked the first time the word has been formally used by the executive branch.