Why is it important for presenters to incorporate audience engagement?

“…it isn’t our schools that are failing: it is our theory of learning that is failing.”

— Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown, authors of A New Culture of Learning: Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change.

An inconvenient truth

Think back on all the conference presentations you’ve attended. How much of what happened there do you remember?

Be honest now. I’m not going to check.

Nearly all the people to whom I’ve asked this question reply, in effect, “Not much”. This is depressing news for speakers in general, and me in particular as, since the publication of Conferences That Work: Creating Events That People Love, I have been receiving an increasing number of requests to speak at conferences.

When I ask about the most memorable presentations, people (after adjusting for the reality that memories fade as time passes) tend to mention sessions where there was a lot of interaction with the presenter and/or amidst the audience: in other words, sessions where they weren’t passive attendees but actively participated.

Take a moment to see whether that’s your experience too.

Social learning

Conference sessions that are designed to facilitate engagement between rather than broadcast content provide wonderful opportunities for social learning: the learning that occurs through connection, engagement, and conversations with our peers.

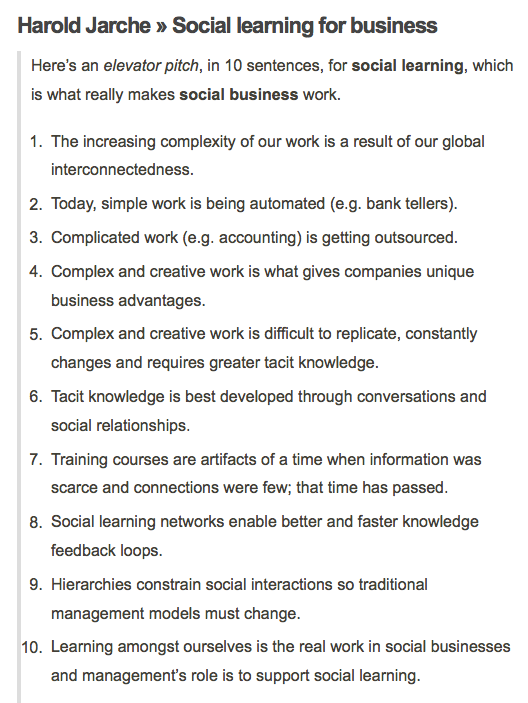

Social learning is important, and here’s why, courtesy of Harold Jarche:

There are additional reasons why supporting social learning during conference sessions makes a lot of sense:

- Active participants almost always learn and retain learning better than passive attendees.

- Participants meet and learn about each other, rather than sitting next to strangers who remain strangers during a session.

- Participants influence the content and structure of the session toward what it is they want to learn, which is often different from what a presenter expects.

- Being active during a session increases engagement, creating better learning outcomes.

- Actively participating during a session is generally a lot more fun!

A mission for conference presenters: incorporate audience engagement

Conferences provide an ideal venue for social learning; they are potentially the purest form of social learning network because we are brought together face-to-face with our peers. And yet most conference sessions, invariably promoted as the heart of every conference, squander this opportunity by clinging to the old presenter-as-broadcaster-of-wisdom model.

Of course, there are conference sessions that routinely include significant participation. Amusingly, they have a special name so they won’t be confused with “regular” conference sessions: workshops!

In my opinion, every conference session longer than a few minutes should include significant participation that supports and encourages engagement. If you’re a conference presenter, make this part of your mission—to improve your effectiveness by incorporating participation techniques into your presentations. Your audiences will thank you!

Are you a conference presenter? How much do you incorporate participation techniques into your presentations? Please share your ideas here!

Adrian you bring up very important questions. Questions I have asked for a while. I think it has taken until now when we had enough of a mass to shift into creating these types of conferences.

Before I was told “we don’t do it that way, our method works for us”.

Now that the audience has as powerful a megaphone as the conference promoters, we can be a bigger wheel that squeaks.

Love that people are starting to show by their participation which they find valuable. Of course you have to offer it before feet can walk.

I think what’s under-explored when this topic comes up is motivation. Presenters at conferences aren’t necessarily motivated by how much people learn in their session. Sometimes the “broadcaster-of-wisdom” model is fine with them, if they are then seen as a “possessor-of-wisdom.” I’d like to see more discussion on the question of aligning the motivations of presenters and participants and meeting owners. Some of this might have to do with compensating presenters, some of it might have to do with selection, some maybe is other things I haven’t cast much thought on yet…

You bring up a good point, Meredith. If a presenter is concentrating on looking good/wise/smart, the audience members may not get what they need. The meeting owner should make her needs clear, but this often isn’t done (or those needs may be more about making money on the event to the detriment of the quality of what happens there). And yes, when presenters aren’t compensated appropriately for their work, they will understandably look for other ways to make their stage time work for them.

In my experience, the most successful events (where success is agreed on by all three of the players you mention) are indeed those where their motivations are aligned as closely as possible.

I agree with many of Meredith Low’s comments. One point I’ll add is exploring the process of securing presenters and confirming their overall method of delivery. I have found with select clients that they focus on securing a presenter to fill a specific topical area…but that’s as far as it goes. They don’t always “work” with the presenter to leverage expectations on how they will actually run a workshop or session. That’s where opportunity lies. There needs to be more engagement at the outset to ensure you will receive more than just someone talking “at” the audience rather than engaging them. It takes work, but it’s worth it.

Right, Jennifer, many organizers select presenters on the basis of their content expertise and don’t consider the presenter’s process expertise—or lack of it. It’s perfectly acceptable to ask a presenter to concentrate on a specific topic, but, somehow, impolite to ask them (or request) how they are going to present it.