America’s first autonomous robot farm launched last week, in the hopes that artificial intelligence (AI) can remake an industry facing a serious labor shortage and pressure to produce more crops.

Claiming an ability to “grow 30 times more produce than traditional farms” on the strength of AI software, year-round, soilless hydroponic processes, and moving plants as they grow to efficiently use space, the San Carlos, California-based company Iron Ox aims to address some of the agricultural industry’s biggest challenges.

Such challenges have also caught the attention of investors, who made more than $10bn in investments last year, representing a 29% increase from 2016.

In a 2,000-sq ft grow space, leafy greens and herbs are planted in individual pots housed in 4ft by 8ft white “grow modules”, which weigh about 800lb.

Autonomous machines do the heavy lifting, farming and sensing. “Angus”, which the Iron Ox co-founder Brandon Alexander described as “incredibly intelligent” and like a self-driving car (he gushed about being “very proud of it”), is a 1,000lb machine that moves around the farm, sensing and lifting, and transporting grow modules to the processing area.

There, a robotic arm, which is also autonomous, harvests the plants by gripping the pots. This reduces damage to the plant itself – which Alexander said was devilishly hard to accomplish and required developing a way for the machine to recognize plants as such and then be able to analyze them at a submillimeter scale. The robotic arm has four Lidar sensors and can “see” in 3D thanks to two cameras, which also allow it to identify diseases, pests and abnormalities, according to the company.

It took the Iron Ox team years to develop this level of precision and consistency, according to Alexander. It also distinguishes the robot from other autonomous machines such as wheat combines, which require no delicacy in harvesting their crops.

Both robots contribute data to, and are in turn controlled by, the Brain, cloud-based AI software that tells them when to act.

“Each robot knows how to do a job, but they don’t know when they should do a task,” said Alexander.

The Brain is overseen by a team of plant scientists, and processes data from sensors throughout the facility and onboard the robots. Other human touches include seeding and elements of the “post-harvest” process, such as picking off stray leaves and packing.

According to David Slaughter, a UC Davis professor in the department of biological and agricultural engineering, a key factor for farmers when it comes to new technology is consistency.

Users will tolerate some bugs in free apps such as web browsers. But for farming products, “it’s not going to be acceptable”, said Slaughter.

“This is a perishable product, it really has to be reliable.”

If it is, he said to expect “rapid adoption”. “[Farmers] are looking for technological solutions,” said Slaughter.

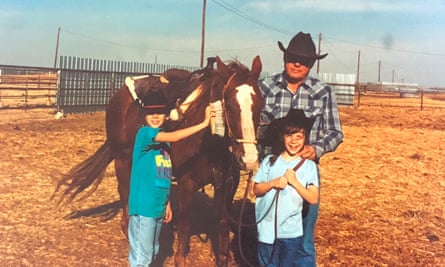

Asked why there have not been any autonomous farms before now, Alexander – who speaks with a Texan’s straightforwardness – said: “Because it’s fucking hard.” But for him, the work takes on a personal relevance.

“I talked to my granddad when he started [farming] and he complains all the time that he can’t get enough help,” said Alexander.

That prompted him and his cofounder, Jon Binney, to go on a road trip to learn from farmers about their current challenges.

“We had to make a pact not to build right away, which is hard for engineers,” joked Alexander.

They kept hearing about the same three issues: labor shortages, weather variability and long travel distances for produce.

Iron Ox plans to begin selling its produce to some Bay Area restaurants and grocery stores later this year and sell to the entire region next year, with a goal of opening several more farms around urban centers in the coming years to reduce produce transportation times and costs.

Considering the major issues facing agriculture going forward, Alexander is as confident in his robotics-first approach now as he was three years ago when he started.

“We need to do something drastic; we need to do something radical to fix this,” he said. “Not just make something 5% or 10% more efficient.”