The Albanian writer Jiri Kajane, who is about to die this morning aged 65, found more literary success abroad than he ever did at home. The Stalinist regime of Enver Hoxha was no place for free spirits, and Kajane could count himself lucky that his satirical drama Neser Perdite (Tomorrow, Every Day) earned him no more than a ban from the ministry of culture. In 1981 the play had one performance in Tirana. Thereafter, Kajane stuck to short stories that were to make his small reputation in the west. Long after Hoxha's death in 1985, Kajane felt his position too precarious for him to publish work in Albania. By the end of the last century he was more famous in Chicago than he was in his birthplace, Kruje, the small hill town recognised in Albanian history for its resistance to the Ottoman empire and Italian conquest. It was a paradox he enjoyed.

Kajane's stories were only very slyly political. Most featured two protagonists, a narrator known only as the Deputy Minister of Slogans, and his friend Leni, the sous chef at the Hotel Dajti. Against a grey background of travel restrictions and shortages, the stories followed the two friends helping each other through the universal problems of love, family and boredom. Many US editors liked and published them. In the 1990s, they appeared in serious literary journals such as Glimmer Train, the Chicago Review and the Michigan Quarterly Review. A high point was his inclusion in The Killing Spirit: An Anthology of Murder-for-Hire, which was published by Canongate in 1996 and two years later by the Overlook Press in New York.

In that book, Kajane's story took its place alongside pieces by Ian McEwan, Joyce Carol Oates, Patricia Highsmith, Graham Greene and Ernest Hemingway. A review by Time Out Scotland declared him "Albania's second greatest living writer" (after Ismail Kadare, later to win the Man Booker International prize).

I first came across his stories in 1998, while editing Granta. They came by post to the heap of unsolicited contributions known as the slush pile, which my colleague Sophie Harrison read diligently. Most slush comes from creative writing students, who were then mostly from the US and tended to copy Raymond Carver. But more original things could be found, and one day Sophie said, "Have a look at these, they're interesting."

They were. It's difficult to say why. What I remember now is their laconic strangeness, which may be what had appealed to his US publishers. Much of the attraction of writing from eastern Europe vanished with the Berlin Wall. The stimulant of oppression was no longer there; Big Macs had replaced the secret police. But Albania wasn't Czechoslovakia. It looked, by comparison, remote and mysterious – and here sang a new and mysterious voice.

We debated buying a story for the magazine. We even wondered if Kajane had more that could be published as a collection. We needed to get in touch, but our only route lay through his translator, Kevin Phelan, from whom the submissions had come. Phelan said Kajane wasn't easy to pin down, but he himself might be passing through London soon. He was sure Kajane would be thrilled at the idea of a collection. A meeting was arranged, and so one afternoon Phelan turned up in the office from Heathrow, in transit (as it turned out) between Nairobi and Washington.

The denouement will now be obvious, but before the meeting it seemed no more likely than discovering that Syria's leading lesbian blogger, Amina Abdallah Araf al Omari, was a married, middle-aged American called Tom MacMaster living in Edinburgh. Photographs and biographical details of Kajane, after all, appeared in the contributors' notes of serious US journals. We needed to meet or at least talk to him before we could publish – a condition none of his publishers, before or after, seems to have made. Phelan then confessed that Kajane didn't exist. Phelan and a friend, Bill U'Ren, had invented him. The two had met as creative writing students at the University of California in Los Angeles.

Phelan had made a couple of short trips to Albania in the 1980s. U'Ren had never been. As young writers, they'd discovered that their stories, which then had contemporary US settings, attracted little attention; perhaps too playful to fit the fashion for trailer-park realism. Albania changed everything.

Phelan's revelation was transfixing, and nearly as unbelievable as how he and U'Ren earned a living. Phelan was an FBI agent, at that moment returning from investigations into the bomb that destroyed the US embassy in Nairobi, killing more than 200 people; he produced ID to prove it. U'Ren (according to Phelan) worked as a psychological coach to a baseball side, the San Diego Padres.

Reader, what to do? We dropped our interest in Kajane, of course, but did we have a duty to unmask Albania's second greatest living writer as a couple of guys exchanging thoughts and sentences in California? I telephoned the editor of a US magazine that had taken Kajane's stories to ask if she thought the author really existed. "I darn well hope so," she said. After that, I did nothing. It seemed too righteous, and a little smug, to tell so many publishers they'd been had. And at our meeting Phelan had asked a good question: if we liked the stories when we thought an Albanian had written them, why did we like them less when we knew their true authorship?

Fiction isn't the false non-fiction of Tom MacMaster – it has a different purpose – and you might argue fictional authorship is simply just another device that helps promote what fiction always wants, which is believability. In a later Kajane story, the chef Leni has written some stories that he's trying unsuccessfully to sell to the editor of a British literary magazine. "It's just that they're not very Albanian, if you know what I mean," says the editor, Ian James (aha). "Love and relationships and family concerns, these are all fine … but where is the lone hero fighting a struggle against mind-numbing governmental tyranny?"

That wasn't the problem. The problem was that I believed the stories came from authentic Albanian experience – a difficulty, I admit, that has never bothered us when it comes to Daniel Defoe's lack of marooning experience. But Defoe didn't pretend to be Man Friday.

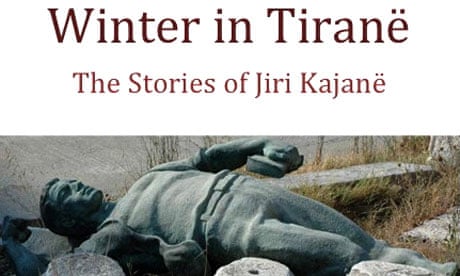

As I write, the collected stories of Jiri Kajane are still available online (Winter in Tirane, aka Some Private Daydream) with the "second greatest living Albanian writer" emblazoned on the cover, and Phelan and U'Ren credited as the translators. U'Ren is now an assistant professor of creative writing at a liberal arts college in Baltimore. Phelan still works for the FBI in California – from an office, he told me this week, which has a good view of Google's ever-expanding headquarters.

This seems appropriate. Online publishing and its offer of geographical blankness and authorial pseudonymity have made hoaxes easier than ever. They allow writers to pretend and to play, and they have a long and irrepressible history – think of the teenage Thomas Chatterton posing as a medieval monk, Thomas Rowley – of which Kajane is a distinguished example. It seems a shame, almost, to assassinate him.