Long before NASA's famed Shuttle program came to a close, the biggest space ambitions of many an American had already withered

"We have put men on the Moon. Can people live in space? Can permanent communities be built and inhabited off the Earth? Not long ago these questions would have been dismissed as science fiction, as fantasy or, at best as the wishful thinking of men ahead of their times," a 1975 NASA design study begins. "Now they are asked seriously not only out of human curiosity, but also because circumstances of the times stimulate the thought that space colonization offers large potential benefits and hopes to an increasingly enclosed and circumscribed humanity."

In the wake of the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, the dwindling resources of the Earth were on the minds of many. The solution, for a particular kind of Big Engineering adherent, wasn't to reduce the human footprint on this planet, but to extend it beyond the blue marble.

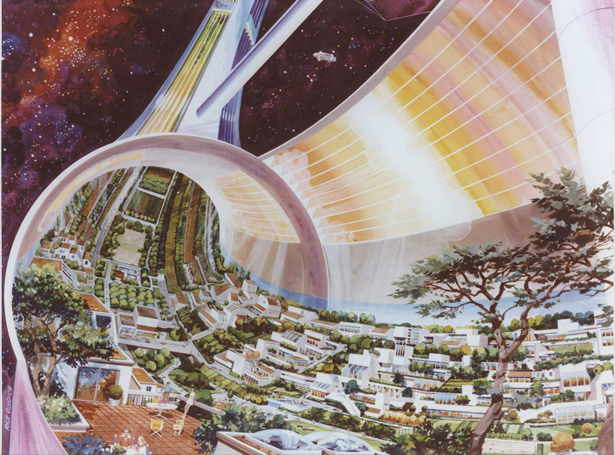

The space colony (a.k.a. space city for those who didn't like the baggage of the word 'colony') movement probably marks the apex of nominally realistic ambitious thinking about off-world living. The goal was to build a 10,000-person orbiting community with materials and technologies available to people in the 1970s. The wildly ambitious effort was centered at NASA Ames Research Center, a neighbor of Stanford University, which had to be the coolest place in the world during the third quarter of the 20th century.

Story continues after the gallery.

In a wonderful bit of mental flexibility, space colonies had a distinct ecotopian bent. I mean the latter adjective to refer specifically to Ecotopia, Ernest Callenbach's 1975 fantastical voyage into a near-future in which the upper west coast has seceded to become a paradise for lovers of what was known as "appropriate technology." (Check out those floating wind turbines!) Appropriate technology was supposed to be scaled to human-needs and not energy intensive, though the term quickly came to encompass a bunch of other stuff that was mainly united by its lack of "high technology."

It's fascinating that this vision of appropriate technology, popularized by E.F. Schumacher in a book called Small Is Beautiful, was so easy to beam up to space with so many of its particulars attached. There's even a "human-powered airplane" in one of the illustrations.

It's not actually hard to see why such a thing was possible, this marriage of high and appropriate technology. Conceptually, the colonies, while they required massive resources to build, would have been self-contained human communities without easy access to Earth's supply chains. They would have been frontier towns in space and as such would have had to prize self-reliance, closed-loop design, and alternative energy. Not only that, but the space colonies would have run satellite solar power stations (an idea that still kicks around now and again), providing them with a reason to be and an income -- and obviating the need to develop the more high-fallutin' forms of nuclear power like breeder reactors.

Practically, the space colony and counterculture met at the Stewart Brand-led magazine, CoEvolution Quarterly. Brand gave Gerry O'Neill, the technical director of that NASA design study, room to make his case in the pages of the "peculiar magazine" known for its brilliant countercultural quirkiness about decidedly more earthly issues. Here's O'Neill selling his plan to CQ's readers:

That frontier can be exploited for all of humanity, and its ultimate extent is a land area many thousands of times that of the entire Earth. As little as ten years ago we lacked the technical capability to exploit that frontier. Now we have that capability, and if we have the willpower to use it we can not only benefit all humankind, but also spare our threatened planet and permit its recovery from the ravages of the industrial revolution.

Some of the magazine's readers thought the plan was nuts, so Brand gave them a chance to respond within the pages. Some of the quotes are interspersed with the illustrations of the space colonies that top this post.

Like so many visions of the future, the space colony model as promoted by O'Neill tells us as much about 1975 as it does about low-earth orbit's ultimate potential. And somehow, I suspect that's why Brand gave the idea so much play.

Now, looking back at this paleofuture, we can see our own time reflected in this dark mirror from the past. Tim Maly, who dug up these old drawings a few days ago, makes a wonderful point about the mechanics of these drawings (or, I would argue, the texture of old language).

The painting is really a cognitive hack. It works the same as our habit of referring to pocket computers linked to satellite radio networks as "phones" or the fact that "wireless cable" is a meaningful term. The yuppies and motorboats on the artificial river are trojan horses and reference points to help us grasp the sublime scale of a half-kilometre glass ball that traverses the heavens with people inside. The interior has to be banal. It makes the future seem more believable for a time. It makes the future easier to accept.

Until that time passes and the depicted future is not built. When that happens, neither the future nor the reassuring veneer of past-present is familiar. Instead, you get these strange fantasy objects, unstuck from time. It's a wholly alien environment combining stuff we don't have anymore with stuff we never got.

And we didn't get any of this stuff. No longer can we begin to imagine that we'd build space colonies in outer space. Serious intellectuals and writers couldn't even be bothered to handwavingly dismiss such an enterprise. Hell, in two days, we won't even have a Shuttle to get to the International Space Station, the tiny, shriveled, boring version of the wild future a few influential dreamers once thought they could build.

Via Tim Maly.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.