A year-and-a-half since Britain voted to leave the European Union and Jeremy Sosabowski, co-founder of AlgoDynamix, says the technology scene remains solid: There’s plenty of money out there for entrepreneurs and little sign that it will dry up anytime soon.

“It looks very robust,” said Sosabowski, whose company provides risk forecasting for financial markets and has raised money from Amadeus Capital Partners. The firm has offices in London and Cambridge. ”It’s almost worryingly robust.”

Below the surface there are reasons to be concerned, but the data so far looks positive. UK companies raised $7.7 billion last year, more than double that of 2016, according to Dealroom. Fintech companies raked in $2.9 billion, the biggest share. TransferWise raised £211 million ($286 million) while Funding Circle took in £81.9 million, according to lobby group London & Partners.

While the number of deals has potentially declined, the size of the transactions has increased, according to Frederic Lardieg, an early stage investor at Octopus Ventures. ”Five years ago it wasn’t possible to do deals of this size,” he said.

The results seem to refute skeptics who said Brexit was a self-inflicted injury that would damage its economy—including its budding sector for startups. Of course, it’s an imperfect experiment: Nobody knows how much money companies would have raised had UK stayed in the EU. But for now, London has retained the center of gravity when it comes to European fintech.

The government has tried to shield the sector. It stepped up its overseas trade missions, for example, which are meant to introduce British startups to customers and investors. UK regulators’ “sandbox” to help financial companies get started has been credited with fostering innovation.

Access to talent has been one of the biggest worries since Brexit. Some EU nationals might not want to live in the UK because of uncertainty over their work status, or may simply feel less welcome since the vote. With that in mind, prime minister Theresa May sought in October to reassure EU citizens living in the UK that they would be able to stay. The prime minister made a similar pledge during negotiations with Brussels in December.

These signals are symbolic but important, said Maria Scott, CEO of TAINA Technology. The executive said she hasn’t noticed a big difference since Brexit when it comes to hiring hard-to-find talent.

“We were paranoid about access to talent,” said Scott, whose company specializes in regulatory technology for banks and is based in London. ”We can’t be complacent—the government needs to continue doing the right things.”

There are reasons to be cautious. Stock markets in the US and UK are smoking hot this year, suggesting investors may be overlooking some risks. Sosabowski of AlgoDynamix acknowledged that it almost “feels too good to be true.”

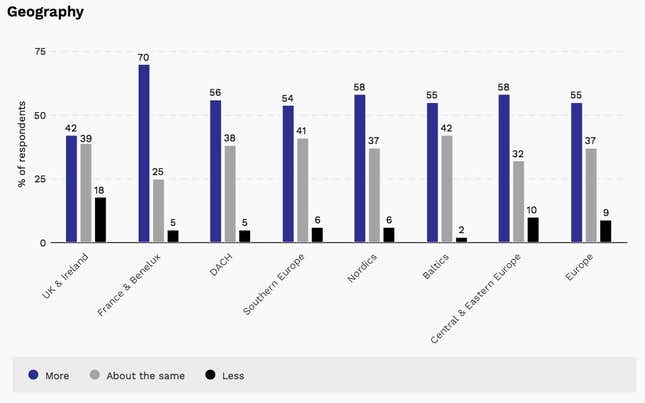

Attitudes across Europe are diverging. While the UK is the No. 1 destination for investment, entrepreneurs in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (Benelux) are substantially more positive about the future of Europe’s tech scene than their peers in Britain: 70% of the former are more optimistic than they were 12 months ago, compared with 42% in the UK and Ireland, according to a survey by venture capital firm Atomico.

Politics have played a part in that optimism, particularly in France where president Emmanuel Macron was elected a little more than six months ago. Olivier Goy, founder of crowd-lending platform Lendix, says he’s even more positive about France’s potential than he was after the poll. In an interview in Paris last month, Goy said the administration listens to what entrepreneurs have to say and has taken steps to make the labor market more flexible.

Another concern is the European Investment Fund, a public-private partnership that plays an important role for venture capital in the region by helping draw private cash into the funds it contributes to. The UK is looking to use its British Business Bank to take up the slack if the EIF no longer favors UK funds and firms. But there are still questions about how quickly the BBB’s money can be deployed and whether there could an interruption in funding, said Tom Wehmeier, partner and head of research at Atomico.

Venture capital firms are less easily wooed by a pitch deck claiming a firm specializes in blockchain or artificial intelligence, according to Ryan Edwards-Pritchard, managing director at London-based Funding Options.

Despite signs the market could be overheating, he says funds have a healthier attitude than they did a few years ago and are looking for businesses that can generate revenue and, ideally, break even. Still, Edwards-Pritchard, whose firm is raising money, said there’s “strong interest” from around the globe in UK fintech companies. For now, the sun is shining for startups.