SUMMARY

Viewed through the lens of developmental psychology, the United States can be seen as a late-stage adolescent as opposed to a nation in decline. This analogy may help explain some of the recent vicissitudes in American popular and political culture, and theories of developmental psychology may help chart a path toward reducing polarization.

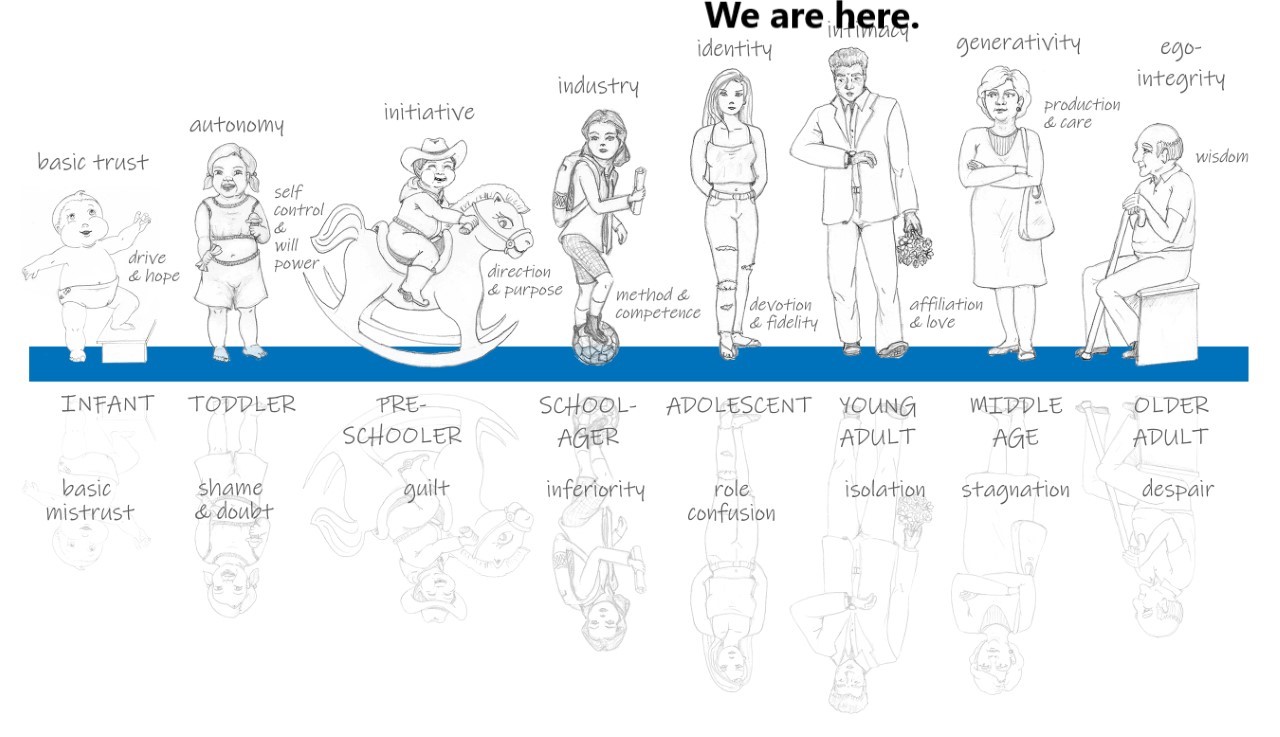

America’s century has “closed,” according to commentators.¹ However, if seen through the birth-to-death lens of developmental psychology, America is not an aging country on the edge of demise, but a late-stage teenager on the verge of young adulthood. In this premise lies promise. And a job. Our country’s chief occupation for the next several decades is the same as any late-stage teenager, namely surviving adolescence without crashing the car, burning down the house or destroying our reputation. During the last 12 months, America seems to have come perilously close to driving the car straight through the front door and setting the whole house alight. As a good high school counselor would advise any teenager about to leave the nest, this is the moment for the country to make fundamental decisions that will shape its future trajectory. Viewing America as a late-stage teenager is supported by at least 13 developmental constructs.² But one need not be a developmental expert to see the connections. A quick scan of the headlines in the U.S. underscores this premise with equal measures hilarity and horror. More important, this construct instills hope because in this connected developmental idea lies the power to explain much that feels inexplicable. When toddlers are frustrated and unable to articulate what they are feeling, they throw tantrums. Adults do the same. And our country is full of motive-bashing tantrums that seem rooted in an inexplicable frustration. Where Americans are feeling eddied in the same cycles and circles, the human development scaffold offers an insightful framework in climbing above today’s divisions and helping us jointly construct a more stable table.To understand where we are today, consider America-the country-as a developing individual. Through this lens, she has already crawled and then walked through the first four commonly identified stages of human development, working her way through the first formative years. The look back paints a compelling picture.

.image-layout–one .image-layout__figure:nth-child(2), .image-layout–one .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3), .image-layout–one-inset .image-layout__figure:nth-child(2), .image-layout–one-inset .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3), .image-layout–one-inset-small .image-layout__figure:nth-child(2), .image-layout–one-inset-small .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3), .image-layout–two-stacked .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3), .image-layout–two-offset .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3), .image-layout–two-symmetric .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3), .image-layout–two-asymmetric .image-layout__figure:nth-child(3){ display: none; }

However, with the death of that initial revolutionary generation, the country’s vision of itself changed. As Abraham Lincoln noted in his famous 1838 address to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois:When America was a newborn and toddler, she carried that red, white and blue blanket Aunt Betsy made everywhere. She hung onto every word her Founding Fathers wrote and thought them wise and wonderful. She loved her name and her home and enjoyed imagining her future.

“[T]hose histories are gone. They can be read no more forever. They were a fortress of strength; but, what invading foeman could never do, the silent artillery of time has done.”3

The passage of this cohort presaged the country’s passage into full childhood when the divided house was nearly torn down in a bloody civil war. While America may have lost her innocence, the conflict’s conclusion bound the American family of states all into an eternal union. The era bookmarked by Reconstruction through the end of the Eisenhower administration can be seen as the country’s preteen years. Like a sixth grader trying out for a school play, the country took its first hesitant steps onto the world stage. Then, like that same student grabbing the limelight on the last day of middle school, the country strode proudly upon the boards, confident that it belonged. Then, a decade or so before her 200th birthday, America hit puberty. Suddenly, the forefathers sounded not the least bit intelligent, and the country started questioning, well … everything. Across America, once-staid popular culture took on a psychedelic sheen. Experimentation was the rage. Like a teenager not understanding the rush of new sensations, the country grappled with new ideas. Playing out this analogy, over the past few decades America has been a full-fledged teenage band. We’ve been immortal, eating and drinking without a care for the consequences. We have been egocentric, certain the world is orbiting around us and making a study of our every move. We’ve been cliquish with an inflated view of our own capabilities. We’ve divided the world into devoted friends and fierce enemies. We can tell you everything about the hottest person with the most followers in class, but little about the needs of our neighborhoods, much less the needs of our global neighbors. We’ve dropped our global pen pals and trained our gaze on the mirror, where we continue our study of self with selfie smiles and documentation. We’ve amassed long lists of friends-but they have been surface-level friends who reinforced our worldviews. And we haven’t cared who owned the proverbial or literal car, so long as we had the keys and gas. The question of “Who am I?” has been heavy on the mind of this late-teen America. Consistent with teenage development, this crisis of identity feels all-consuming. Developmental psychologists have long noted that these struggles produce a general state of dissonance-mid-self-discovery, manifesting in myriad ways from violent outbursts to studied cynicism. As parents throughout America’s history have reminded their teenage children, whether they were leaving home for a night on the town or to seek their fortune on the frontier, the choices made now will influence the rest of their life. Similarly, the decisions we as a country make now will have formative impact on the nation of our teenagers’ children. While this construct may in some ways oversimplify 250 years of American history, the developmental comparative has uncanny connections that explain our national sense of angst. These ideas also point to a path forward, which is particularly important right now. Developmental psychology as understood by Jean Piaget, Erik Erikson, Lawrence Kohlberg, Carol Gilligan, Michael Commons(4) and others provides a useful framework for our immediate growth around which we can build American parallels.(5) Like people, nations may get older, but their policies and politics do not necessarily grow wiser. Some people leave this plane of existence having met the maturational development milestones but with the emotional capabilities of an 11-year-old. The growth we choose, rather than chronological milestones, separates the simply old from the wise. Chosen development is about the quality and nature of thought and is a form of intellectual, emotional and spiritual achievement to which both an individual and the nation should aspire. Americans’ ability to feel and share collective empathy may prove to be the highest hurdle. When confronted with suffering, we assume most people will empathize. However, developmental research shows that about 75 percent of the U.S. population(6) functions at an egocentric level, meaning most Americans can only understand something as they understand their own feelings and thoughts. Put another way, about three-quarters of U.S. adults would have a really hard time walking a mental mile in another person’s shoes. And if you can step inside another’s thoughts or feelings, it may be useful to realize that you are in the minority, according to Piaget and other hierarchical developmentalists. The first act of getting stronger as a country is an awareness of “We are here.” We have a developmental divide: What makes certain actions “obvious” to a minority of the population may remain quite invisible to the majority. This is not something that can be legislated, mandated or quickly taught. But with intention, we can promote and learn abstraction and perspective-taking, even as we face our maturational milestones of determining faith, alliances, productive direction and interdependence. As John F. Kennedy put it, “Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or the present are certain to miss the future.”(7)The immediate American future has the potential to be interesting, fulfilling and enlightening. With the excitement of a high school graduate, our nation’s future is before us. This is not our time of decline; this is our time to shine. We have moved as a nation from dependence to independence. Now, the task before us is shaping this country’s declarations of interdependence. America is coming of age. Maturational psychology tells us our country will become set in our ways as we enter adulthood. The wisdom in those “set” ways depends on our willingness to grow and develop with intentionality. As we cross the threshold of maturity into an “adulting” nation, we can let nature take her course or we can shape this clay. The first step of intentional development is simply noticing this moment. We are here. And bidden or unbidden, we are growing up, America. What can we do? We can notice. We can embrace this opportunity for growth. Whether a fender-bender or failed first love, accidents and anxiety leave their marks during the teenage years. Wisdom on both the national and personal level is hard won, but, using developmental psychology as a roadmap and intentionally emphasizing empathy and interdependence, we can chart a path toward a more perfect union.

Lisa C. Uhrik

Lisa C. Uhrik (Peabody, M.Ed ’92, M.Ed ’94) is the author of America Becoming: Framing Our Declarations of Interdependence to be published on July 4, 2021. In addition to writing and speaking, she is co-owner of Franklin Fixtures, a Tennessee-based manufacturing company dedicated to shelving and display solutions. She received two .Ed. degrees from Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College in human resources development and human development counseling, and has completed work toward her Ph.D. in community literacy at Tennessee Technological University.

Addendum: 13 Key Constructs Linking American Development and Developmental Psychology

Adolescence is marked by:1. Egocentrism: worldview rising from self, personal experience2. Paranoia: worldview that others are watching everything about us with interest3. Immortality: sense of invincibility, little concern about present actions and future consequences4. Rejection of authority: need to rethink doctrines, constructs and mores5. Identity/role confusion: quest for definition of self6. Use of social groups and cliques in formation of identity7. Differentiation or alignment: use of others to become “unique” and “different” or to validate self through “likes” and commonalities8. Self-expression: passions, emotions run high; elevated need to be heard and express thoughts and feelings9. Informality: quest for the dismantling of formal structures toward exploration of core connections10. Sexual identity: heavily associated with identity formation, understanding of self and desires as sexual being 11. Quest for “real”: attempts to define reality and formation of existential worldview12. Spirituality/faith development: rejection or acceptance of doctrines and views presented by previous generations; formation of belief and faith along with existential worldview13. Managing emotions: marked by bursts of anger, depression, excitement, passion, optimism, pessimism; noted for wide swings and unpredictable emotional conflicts

Addendum: What Exactly Is Hierarchical Development?

Here are the main things that you need to know about growing your capacities for emotion, thought and understanding with intention-all those things that are hallmarks of hierarchical development:

- It is possible for everyone.

- It is different than intelligence.

- It changes-permanently-the ways we think and learn and know.

- It is necessary for the development of societies and families, where the ability to understand each other and communicate and build things together is important.

Why should you want to develop with intention? Isn’t it good enough to deal with the kind of growth and change that comes with age-both for ourselves and for the country? I like to think of hierarchical development like climbing a mountain: It takes a lot of intentional effort, but when you reach the top, everything you see-and the way you feel-is totally transformed. R stands for Revelation, the “aha” beginning of new learning. E stands for Exploration, where we push deeper to understand the nuances and applications of our new understanding. A stands for Action-it is only through putting these new understandings into action and testing them out through experience that they root and gain meaning. And service action, in particular, is critical to growth: The act of serving others has a unique way of opening our minds and hearts to new awareness. D3 stands for the triple tasks of Discovery, Dreaming, and Declarations of Interdependence: Discovery-stopping to understand what you’ve learned from action; Dreaming-letting those discoveries, good or bad, lead to a compelling picture of the future; and Declarations of Interdependence-actually writing down the things that you intend and by which you will be guided.

Footnotes

1 See, e.g., Robert Stengel, “The End of the American Century,” The Atlantic, January 26, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/01/end-of-the-american-century/514526/. 2 Examples of these developmental constructs that link human development with today’s American culture include:

- Labile Emotions. Adolescents shift moods rapidly, vacillating between happiness and distress, self-confidence and worry.

- Personal Identity. Adolescence is a time when teenagers explore and assert their personal identities.

- Peer Relationships. During adolescence, relationships with peers take precedence and peer acceptance is critical.

- Independence and Testing Boundaries.

- Egocentric perspective. It is often difficult for adolescents to look at circumstances from other people’s perspectives.

3 http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/lyceum.htm 4 Commons, M. L., & Chen, S. J. (2014). Advances in the model of hierarchical complexity (MHC). Behavioral Development Bulletin, 19(4), p. 37. doi:10.1037/h0101080 5 Some key points of awareness cited by such scholars include:

- Maturational development is self-evident and part of our inherent human programming. We have seen these patterns in our children, felt them in ourselves and noticed them reflected in our media.

- Looking at the past 244 years, American development has demonstrated similar patterns to human development. America appears to be going through the same milestones (toddler, childhood, puberty, adolescence …) as a collective, united group.

- Though Americans are fierce about our diversity, our culture (music, entertainment, social media) reflects that we have much in common in maturational developmental terms: We are in “late adolescence” together.

- From this maturational moment of late adolescence, America will make declarations-not of independence, but of interdependence.

- As America is convulsed with the developmental trauma of coming of age, it will be forced to grapple with its faith and identity.

- There are two types of development-the kind that comes simply with time (maturation) and the kind that comes with intention (hierarchical development).

- Hierarchical development is not a biological function but requires intention and effort.

- The question quickly becomes whether the nation is willing to intentionally expend the effort.

6 Developmentalist Roger F. Aubrey, Human and Organizational Development, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, 1990. 7 “Address in the Assembly Hall at the Paulskirche in Frankfurt (266),” June 25, 1963, Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963.