The British record industry made its biggest transition in 1968 - it will not be capped until the time (perhaps in five years?) when tape cassettes overtake record sales. I quote from a recent issue of the “ New Musical Express”: “For the first time ever in 1968, production of albums in Britain exceeded that of singles. A total of 49,184,000 LPs were manufactured during the year, compared with 49,161,000 singles. This figure represents an increase of 11 million albums over the 1967 total.” In America, where over 80 per cent of the revenue of the record industry comes from album sales, it is well realised that “the charts” do not just refer to singles. “Billboard” magazine gives equal prominence to single and album charts.

Comparing the last three albums of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys, the Byrds, or Dylan, is a matter of noting their differences rather than their similarities. This is very much to do with the album as a medium. Bands produce albums about every six months, on average; few can compose 40 minutes of music faster than that. Albums, therefore, make both the musicians and their audience – who have to pay nearly £2 for the record – choosy and thoughtful; both are looking six months forward, and a lot can and should happen in half a year.

Tracks on an album may be connected by style or mood; they may vary in length from 20 seconds to 20 minutes; and the extended studio time and budget needed for an album encourages experiment (for good or bad). One new development is particularly interesting.

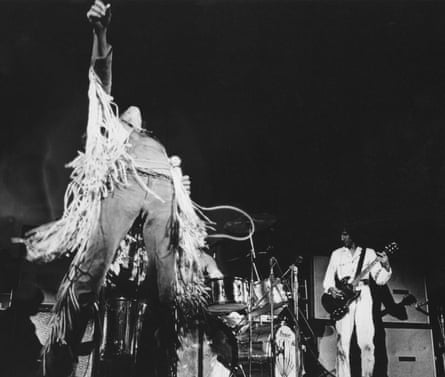

The Who and the Kinks are unapproached in their talent for narrative rock: for telling exemplary stories about everyday people. Their styles are quite different; the Who are ravers, the Kinks are wry. Both bands use solid, mainstream rock music as the base for their intelligent celebrations of people, crystallising history as the best balladeers once did.

“Pinball Wizard,” the Who’s latest single, evidently works; it is currently four in the singles charts. But it is enigmatic. Its hero, who “plays a mean pinball,” gets his free scores and bonuses using only his sense of touch. What is happening?

This single points forward to the Who’s imminent double album, “Tommy,” which is the life of a deaf, dumb and blind boy. Each track on the album (Track records; I will be reviewing it at length soon) shows the world as felt by one very singular, very ordinary person. Pete Townshend’s idea depends on the fact that the album is the medium for rock.

Scenes from the life of one person is a perfect solution to a time of transition, in the record industry, between singles and albums. One scene gets promoted as a single, for maximum airplay; and as an intriguing advertisement for the album. The combination of media has produced the form of the message.

The Kinks have had the same idea. Their next album, provisionally called “Arthur,” concerns the life and times of an Englishman born at the turn of the century, thrown about and confused by wars, the Depression, and, most of all, by the mess made of his mental scheme by the fall of the British Empire. Ray Davies will release a track from “Arthur” as a single; and, again, the idea depends on the medium of albums. And “Arthur” will also be a television show, probably to be put out in Britain this summer.

Radio shows will also pay more attention to album tracks, as the charts are increasingly understood to include albums. And Ray Davies’s television show not only points forward to the time when we will plug video-cassettes into our television sets. It is the first rock music work conceived simultaneously for television and for an album. And such shows may well encroach on those which are packages of the latest best selling singles.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion